The Public/Private AML Industry is Fifty Years Old and is Long Overdue for a Makeover: Let’s Start with Better Public Sector Feedback

What we know as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) has been around since October 26, 1970. The original purpose was to require financial institutions to keep records and file reports that had “a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings”. Other than adding another purpose after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 (reports to support “the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism”), that original purpose hasn’t changed. Fifty years ago a few thousand reports were submitted to law enforcement: this year more than 20 million BSA reports are produced by the private sector and submitted to the Treasury Department’s financial intelligence unit, or FIU – the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

To repeat, the purpose of these BSA reports, indeed of the entire anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) regime, is to provide “a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.”[1]

The production of these reports doesn’t come cheaply. It costs the private sector billions of dollars every year to develop and maintain programs that are ultimately intended to produce and keep these records and to produce and file these reports. And for years the private sector has complained that law enforcement isn’t using the reports effectively and isn’t providing feedback to the private sector as to which reports are useful.

The FinCEN Files – a series of salacious stories based on the illegal disclosure of over 2,100 Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed by dozens of banks – painted some large, global banks as being the reason for, or the facilitators of, financial crime and corruption. Those stories have resulted in calls to reform – once and for all – what the media and others are calling a broken, ineffective, and inefficient regime. But none of those calls for reform offer any solutions. Five recent US government publications provide a more measured – and legal – view into the U.S. anti-money laundering regime and the use, usefulness, and costs of producing those SARs, and other Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) reports filed by tens of thousands of financial institutions. And one of those reports, a September 22, 2020 report on the use and usefulness of BSA reports published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), suggests what needs to be done to streamline and improve the AML regime: we need to “systematically collect information on outcomes from the use of BSA reports”. In other words, there are plenty of inputs into the system – private sector reports of suspicious activity – but we know very little about the outputs from or results of those inputs – what is law enforcement doing with those reports? Which ones are providing actual leads, or tactical information? Which ones are providing trending and analytical value, or strategic information? What agencies are using the reports? All these questions remain unanswered. And although the GAO suggests what needs to be done, it doesn’t suggest how that can be done. I do. The most effective way to systematically collect information so that the private sector producers of BSA reports (financial institutions) can provide reports with a “high degree of usefulness to government authorities” (the very purpose of the BSA), is to require that the public sector consumers of BSA reports (law enforcement) provide feedback to the private sector. And the mechanism for that feedback is the Tactical or Strategic Value Suspicious Activity Report, or TSV SAR.

a more measured – and legal – view into the U.S. anti-money laundering regime and the use, usefulness, and costs of producing those SARs, and other Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) reports filed by tens of thousands of financial institutions. And one of those reports, a September 22, 2020 report on the use and usefulness of BSA reports published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), suggests what needs to be done to streamline and improve the AML regime: we need to “systematically collect information on outcomes from the use of BSA reports”. In other words, there are plenty of inputs into the system – private sector reports of suspicious activity – but we know very little about the outputs from or results of those inputs – what is law enforcement doing with those reports? Which ones are providing actual leads, or tactical information? Which ones are providing trending and analytical value, or strategic information? What agencies are using the reports? All these questions remain unanswered. And although the GAO suggests what needs to be done, it doesn’t suggest how that can be done. I do. The most effective way to systematically collect information so that the private sector producers of BSA reports (financial institutions) can provide reports with a “high degree of usefulness to government authorities” (the very purpose of the BSA), is to require that the public sector consumers of BSA reports (law enforcement) provide feedback to the private sector. And the mechanism for that feedback is the Tactical or Strategic Value Suspicious Activity Report, or TSV SAR.

This article tracks a September 22, 2020 GAO Report on the use and usefulness of BSA reports, and brings in excerpts from other federal government publications where appropriate. This article focuses on three issues described in the GAO report: law enforcement’s use of BSA reports, and whether they find them useful; the BSA/AML compliance cost burden; and regulators’ supervision and examination of BSA compliance programs. The fourth issue – the SAR and CTR thresholds – is included in the compliance cost section.

Finally, and as described above, I offer a solution to how the public sector can provide more effective feedback to the private sector so the private sector can more effectively and efficiently meet its obligations to provide timely, actionable intelligence to government authorities – the TSV SAR. This is not the only solution; indeed, we need more public/private sector partnerships, we need to move to cross-institutional and cross-jurisdictional collaborative investigations, we need more effective information sharing, and we need more efficient and effective monitoring/surveillance, alerting, investigations, and reporting. But the key to any reform is public sector feedback: I’m offering the TSV SAR as the vehicle for that feedback.

Five U.S. Government Publications

FinCEN’s Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) Cost & Burden Estimate

On May 26, 2020, FinCEN published a notice in the Federal Register titled “Proposed Updated Burden Estimate for Reporting Suspicious Transactions Using FinCEN Report 111 – Suspicious Activity Report”. This is a notice required under the Paperwork Reduction Act, or PRA: agencies are required to periodically assess and estimate the burdens and costs of their regulatory regimes.

This was the first such notice where: (1) FinCEN has been able to analysis the SAR Database to quantitatively assess the numbers, characteristics, and types of SARs, by institution type, by type of work required to be done, and by what types of involved positions; and (2) perhaps just as important, FinCEN has shown a willingness to provide this information and to seek feedback from the private sector on other available information that could be incorporated into future analyses. FinCEN must be commended for both.

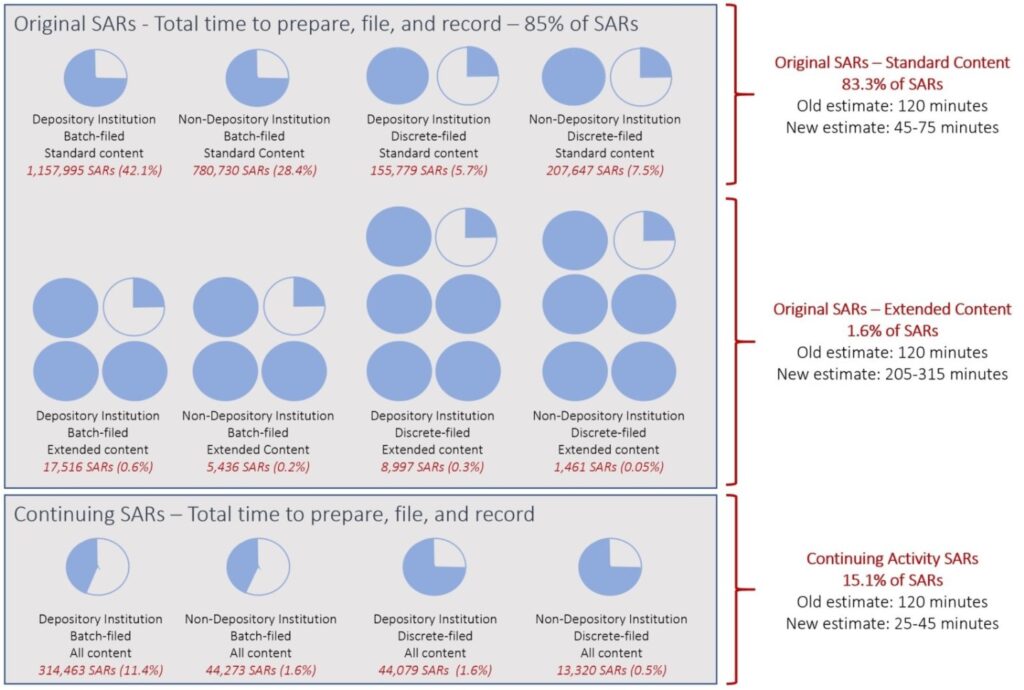

In prior PRA notices, FinCEN has simply estimated that the SAR filing process takes a total of two hours for each and every SAR filed. With this notice, FinCEN identified and attempted to capture burden and cost estimates for five categories of SARs, two types of filing (batch and discrete), three of the six stages in the SAR filing process, and the four types of positions involved in the process.

Five categories of SARs: (1) depository institutions’ (banks and credit unions) original SARs with standard content; (2) depository institutions’ original SARs with extended content; (3) non-depository institutions’ original SARs with standard content; (4) non-depository institutions’ original SARs with extended content; and (5) all filers’ continuing activity SARs. The standard and extended content analysis looked at combinations of (1) the number of named suspects; (2) the number of suspicious activities’ categories marked on the SAR form; (3) the length and make-up of the narrative; and (4) whether there was an attachment.

Six stages in the SAR filing process: (1) maintaining a monitoring system; (2) reviewing alerts; (3) transforming alerts into cases; (4) case review; (5) documentation of the SAR/no SAR determination; and (6) the SAR filing process. The current two-hour per SAR PRA estimate only considered the 6th stage: this notice added the 4th and 5th stage, and FinCEN acknowledged that it needs further data, and comments from the private sector, in order to include the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd stages.

Four types of people: (1) general supervision (oversight); (2) direct supervision; (3) clerical (SAR investigation); and (4) clerical (filing).

With this notice, FinCEN is changing its PRA burden estimate of 120 minutes per SAR to an estimate ranging from 25 minutes to 315 minutes per SAR for the last 3 of the 6 stages in the SAR filing process, and is inviting comments on these new estimates and on how to include and estimate the first 3 of the 6 stages.[2]

US Attorney’s Annual Statistical Report, Fiscal Year 2019

The DOJ statistical reports are available going back to fiscal year 1955 (the federal government’s fiscal year ends on September 30th). They are available at https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/annual-statistical-reports. These reports provide an incredible amount of information on federal criminal cases by US Attorney’s office, by major type of criminal offence, by number of cases filed and completed, how they are completed (guilty, not guilty, dismissed, other), whether dispositioned in district court or by magistrate, length of case, etc.

US Sentencing Commission’s Statistical Information Packets, Fiscal Year 2019

Since at least 1996 the US Sentencing Commission has published summaries of federal criminal cases by district court, by types of crimes, by guilty pleas versus trial, sentence type and term, whether above or below the guidelines and why, etc. The fiscal year 2019 reports are available at https://www.ussc.gov/research/data-reports/geography/2019-federal-sentencing-statistics. The Sentencing Commission data generally aligns with the US Attorney’s data, although there are some differences that I cannot explain (nor have I made formal inquiries). For example, the US Attorneys’ data shows a total of 73,934 defendants pled or were found guilty, while the USSC data shows 76,538 defendants were sentenced. The programs (US Attorneys’ data) and types of crimes (USSC) generally aligned, although there were differences there, also. For example, the US Attorney’s data showed 221 defendants pled or were found guilty under the program heading “money laundering”, while the USSC data shows 1,177 defendants were sentenced for money laundering.

I have included a summary of the Department of Justice’s US Attorneys’ Annual Statistical Report for Fiscal Year 2019. Where the GAO report includes information on how law enforcement uses BSA reports, and whether those reports are useful, it doesn’t indicate how many cases, and what kinds of cases, federal law enforcement agencies bring. Neither the US Sentencing Commission’s Statistical Information Packets nor the US Attorney’s Annual Statistical Report link BSA reports to criminal cases: that remains the undiscovered Holy Grail. Regardless, the US Attorneys’ information is enlightening and, in many respects, concerning.

FinCEN’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rule-Making on BSA/AML Program Effectiveness

On September 16, 2020 FinCEN published a notice seeking public comment for potential regulatory amendments to require all covered financial institutions to maintain an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program that (1) assesses and manages risk as informed by a financial institution’s risk assessment, including consideration of anti-money laundering priorities to be issued by FinCEN consistent with the proposed amendments; (2) provides for compliance with Bank Secrecy Act requirements; and (3) provides for the reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities. The intent of the proposed changes is to “modernize the regulatory regime to address the evolving threats of illicit finance, and provide financial institutions with greater flexibility in the allocation of resources, resulting in the enhanced effectiveness and efficiency of anti-money laundering programs.”

Currently, financial institutions must have programs that assess and manage financial crimes risk and meet the requirements of the BSA laws and regulations. The critical change is the addition of a third program requirement: providing reports that have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities. This is critical: the very purpose of the BSA laws and regulations (set out in the first AML statute in 1970 and codified at 31 USC s. 5311) is “to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.” Currently there is no express requirement that financial institutions’ BSA programs address the very purpose of the BSA.

But as explained in the conclusions and recommendations, there currently is no way to determine what what “useful” means, how it would be measured, and which records or reports are, in fact, useful, and for what purposes.

The GAO Report on Use & Usefulness of BSA Reports

On September 22, 2020, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report that addressed these very concerns about the use made of, and usefulness of, BSA reports, and the costs to produce those reports and maintain the required programs. Titled “Anti-Money Laundering: Opportunities Exist to Increase Law Enforcement Use of Bank Secrecy Act Reports, and Banks’ Costs to Comply with the Act Varied”, the Report was addressed to Representative Blaine Luetkemeyer (R. MO 3rd), the Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions, Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives. The report, GAO-20-574, is available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/709547.pdf.

The Report is lengthy – 214 pages – and covers four main topics or issues and posed two questions relating to FinCEN’s role in BSA/AML supervision and examination:

- Law enforcement’s use of Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) reports – pages 14 to 36 with details and supporting information in Appendix II

- A survey of eleven representative banks’ and credit unions’ direct costs of running a BSA/AML compliance program – pages 36 to 60 with details and supporting information in Appendix III

- A discussion of regulators’ supervision and examination of BSA/AML compliance programs – pages 60 to 65

- A discussion of proposed changes to reporting thresholds, sharing of information, and using innovative technologies – pages 65 to 75

- A discussion whether FinCEN should adopt the SEC practice of issuing “No Action Letters” (Appx V)

- A discussion of whether FinCEN should conduct BSA/AML examinations (Appx VI)

The GAO did its work from September 2018 through September 2020, using information and data from 2015 – 2018. It surveyed six federal law enforcement agencies, eleven banks and credit unions, and six trade associations. The Report is data-intensive: it includes 123 Tables and 16 Figures. Like all GAO reports, it is well written, uses plain language, fairly represents the issues, and, where appropriate, makes recommendations.

Issue 1 – Law Enforcement Use of BSA Reports

The Law Enforcement Agencies

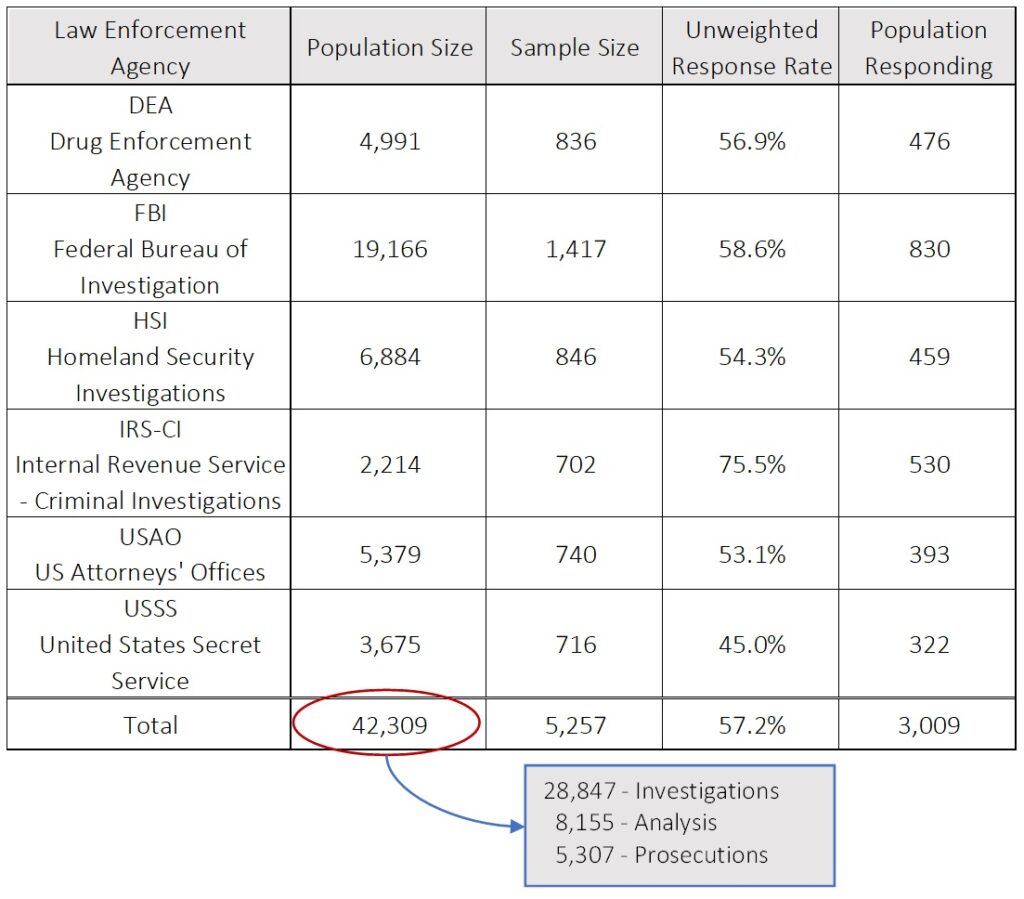

The GAO surveyed six federal law enforcement agencies that were the main users of FinCEN’s BSA database in 2018. I noted that the US Postal Inspection Service was not included.

The table below shows the relative sizes of the agencies, which drive the sample sizes required for statistical integrity. The GAO sent surveys out to select positions within the agencies to get a representative sample. As can be seen, the overall response rate was 57.2%: note the IRS-CI response rate of 75.5%. The IRS-CI also stood out throughout the Report as having higher than average usage rates of all BSA reports.

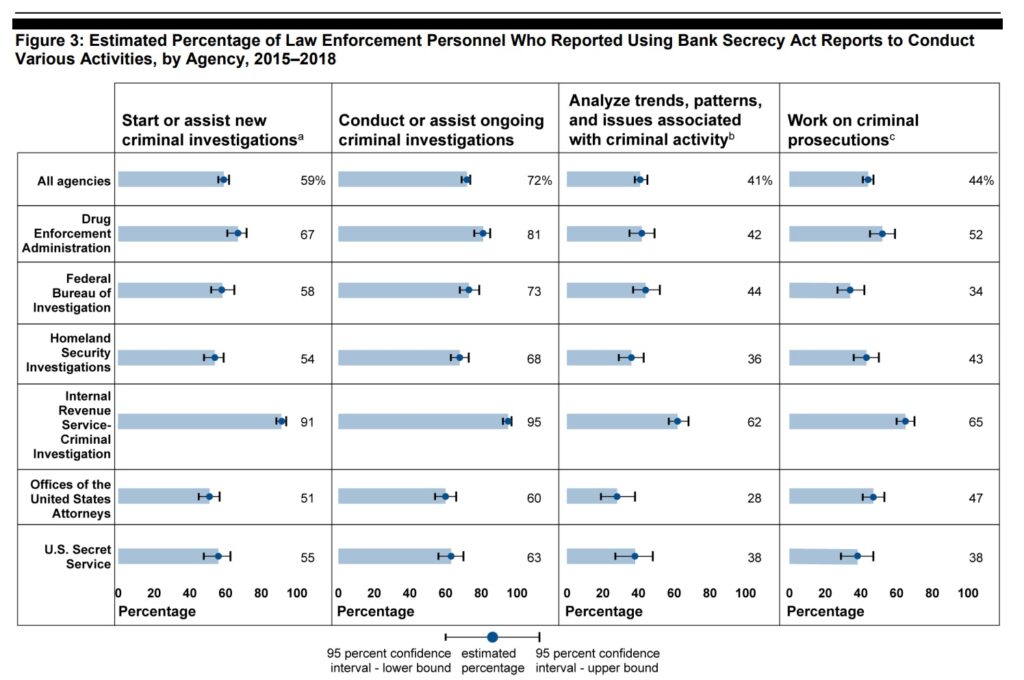

Figure 3, below, summarizes the percentages of law enforcement personnel from the six agencies that used BSA reports to start or assist on new investigations, conduct or assist with ongoing criminal investigations, to analyze patterns, trends, and issues associated with criminal activity, and to work on criminal prosecutions. Almost three-quarters of respondents use BSA reports to conduct or assist with ongoing investigations. Notably, only 41% of the respondents indicated that they used BSA reports for analyzing trends or patterns. And as can be seen in Figure 3, the IRS-CI is a prodigious consumer of BSA reports.

Use and Usefulness of BSA Reports

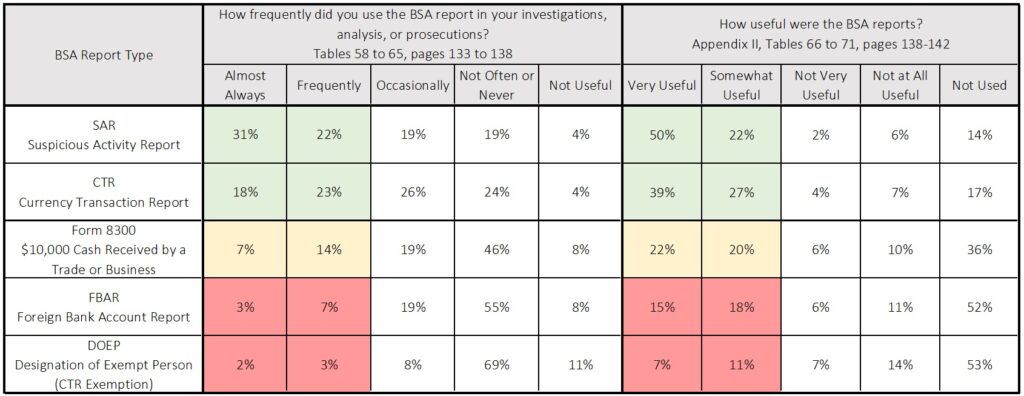

Some of the more interesting findings in the Report are in the details of how frequently law enforcement used the five main BSA reports in their work, and whether they found those reports useful.

The table below is a summary of twelve different tables from Appendix II of the Report. The table provides a high-level snapshot on the use and usefulness of the main types of BSA reports. The color-coding is intended to highlight some of the clear trends:

- Across the six agencies, SARs and CTRs were the most commonly used reports, but still were only used “almost always” or “frequently” about half the time. But when used, SARs and CTRs were found to be very useful or somewhat useful the majority of the time.

- The Form 8300 usage and usefulness data suggests that there is an opportunity for improving the overall utilization of these reports. Forms 8300 are prepared and submitted by non-financial businesses when they receive cash greater than $10,000. For example, a car dealer receiving $12,000 in cash must submit a Form 8300.

Law Enforcement Use of BSA Reports By Type of Potential Crime

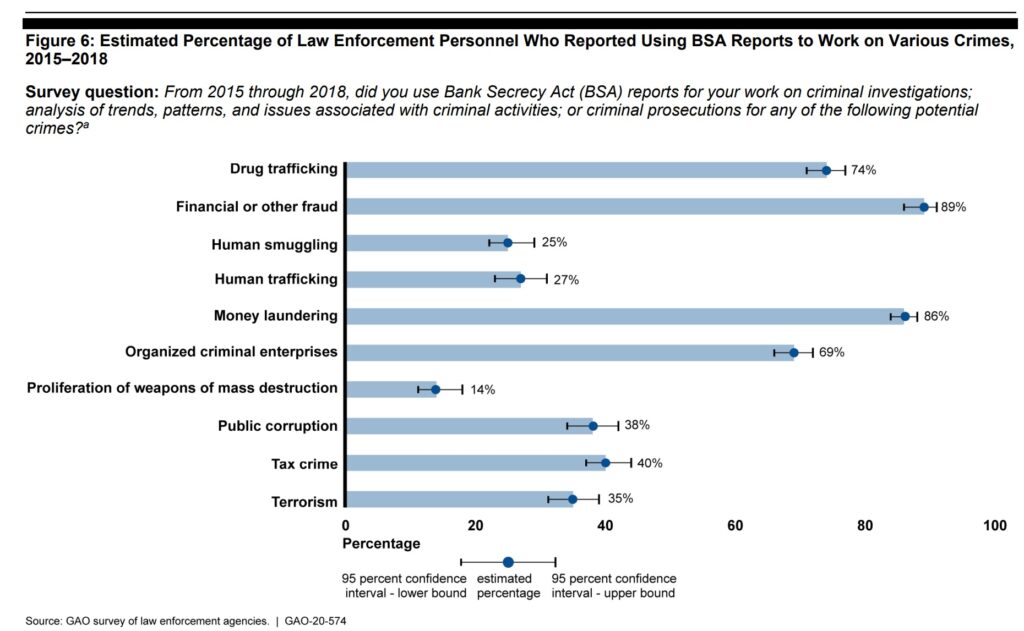

Figure 6 summarized the results of questions posed to law enforcement on whether they used BSA reports for ten criminal activities.[3] I found the 27% positive response rate for human trafficking indicated a potential for better public/private sector outreach.[4]

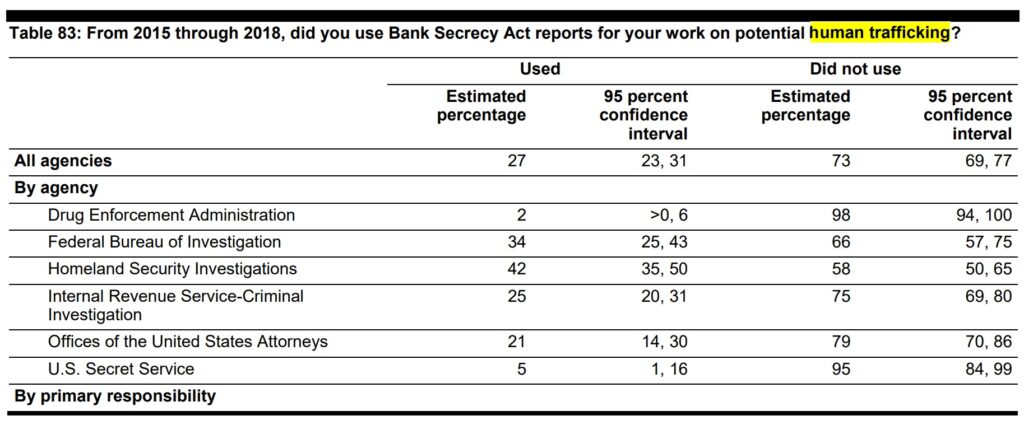

Human Trafficking and BSA Reports

I’ll pause to include some detail on the findings relating to human trafficking, one of the worst crimes impacting the most vulnerable parts of global society.[5] The Report notes that “human trafficking and human smuggling were added to the SAR form as separate suspicious activity categories in 2018. Before that time, personnel working in these areas did not have a systematic mechanism to identify potentially relevant reports when starting investigations or analyzing criminal activities.” And, in a footnote (footnote 60, page 25): “In a 2014 advisory, FinCEN encouraged banks to use common terms to report on human smuggling and human trafficking activities in the written portion of the SAR. According to law enforcement agency staff we spoke with, agencies perform key word searches of SARs to identify reports on a specific topic or activity, but officials with two of the six law enforcement agencies we spoke with noted that the effectiveness of this approach can be limited because financial institutions may use different terms on the form to describe similar activities.”

At page 7 of the Report the GAO notes that “[a]ccording to Treasury’s 2018 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, the crimes that generate the bulk of illicit proceeds in the Unites States are fraud, drug trafficking, human smuggling, human trafficking, organized crime, and corruption.” That, and the revision of the SAR form in 2018 to add a specific category for human trafficking, one would expect that there should have been a lot of human trafficking SARs filed in 2019 and 2020. But that is not the case: in the first 8 months of 2020 FinCEN’s SAR Statistics data (https://www.fincen.gov/reports/sar-stats) shows only 1,822 SARs with the category “human trafficking” (out of 1,574,353 total SARs filed). This is down from 2019 filings: for the same eight month period in 2019, there were 2,478 SARs flagging human trafficking as the suspicious activity (out of 1,527,881 total SARs filed in that period).

Alternatives to BSA Reports?

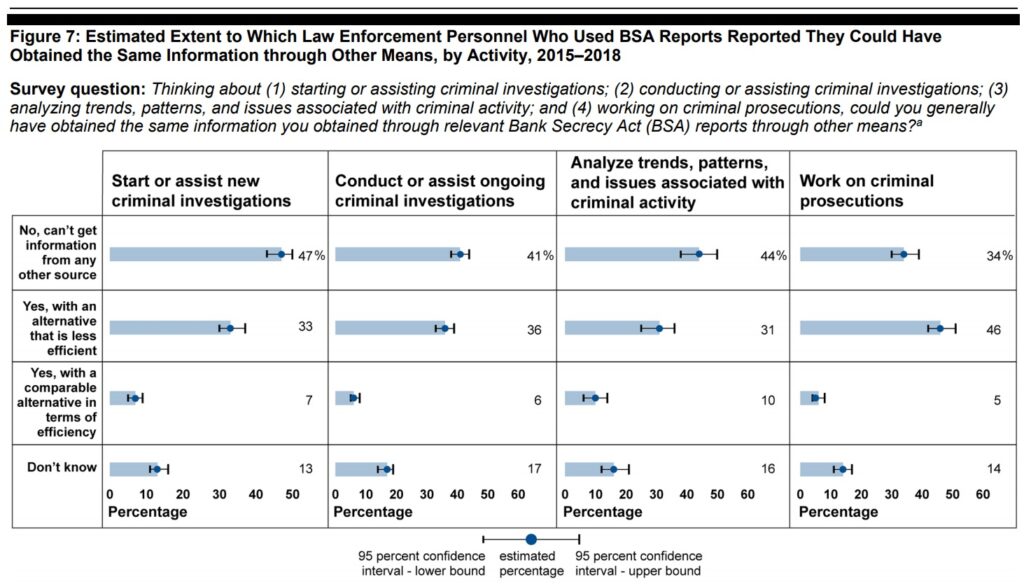

This Report focused on law enforcement’s use of BSA reports, and whether those reports were useful. But the GAO correctly asked questions about whether there were alternatives to BSA reports that were more readily and easily available to law enforcement. At page 25 the GAO wrote: “we estimated that at least 74 percent of law enforcement personnel who used BSA reports in their work on investigation, analysis, or prosecutions from 2015 through 2018 reported either having no alternative source of information or having an alternative source that was less efficient. Those alternative sources include surveillance, warrants, and grand jury subpoenas. Figure 7, below, provides the details.

FinCEN’s Duties and Powers – to Maintain and Disseminate

This section (pages 27 to 35) of the Report addresses the foundational duties and powers of FinCEN, and doesn’t paint a very positive picture. In footnote 63 on page 27 the GAO writes: “Congress gave FinCEN responsibility for operating a government-wide data access service for SARs, CTRs, and other BSA reports. See 31 U.S.C. § 310(b)(2)(B). Treasury is further tasked with establishing and maintaining operating procedures that allow for the efficient retrieval of information from FinCEN’s BSA database, including by cataloguing the information in a manner that facilitates rapid retrieval by law enforcement personnel of meaningful data. See 31 U.S.C. § 310(c).”

The actual language of 31 U.S.C. § 310(b) is instructive. 31 U.S.C. § 310(b)(2) sets out the duties and powers of the Director of FinCEN as follows:

(A) Advise and make recommendations on matters relating to financial intelligence, financial criminal activities, and other financial activities to the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Enforcement.

(B) Maintain a government-wide data access service, with access, in accordance with applicable legal requirements, to the following: (i) Information collected by the Department of the Treasury, including report information filed under subchapter II of chapter 53 of this title (such as reports on cash transactions, foreign financial agency transactions and relationships, foreign currency transactions, exporting and importing monetary instruments, and suspicious activities) …

(C) Analyze and disseminate the available data in accordance with applicable legal requirements and policies and guidelines established by the Secretary of the Treasury and the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Enforcement to– (i) identify possible criminal activity to appropriate Federal, State, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies; (ii) support ongoing criminal financial investigations and prosecutions and related proceedings, including civil and criminal tax and forfeiture proceedings … (v) determine emerging trends and methods in money laundering and other financial crimes; (vi) support the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism; and (vii) support government initiatives against money laundering.

These three duties and powers can be summarized as (1) providing advice to the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Enforcement, (2) maintaining an accessible FinCEN BSA database, and (3) analyzing and disseminating financial crimes data to federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies. The GAO report concludes that FinCEN can improve in two of its three duties.

Law Enforcement Access to FinCEN’s BSA Database

The GAO found that 85% of federal agencies had direct access to the FinCEN BSA database, but only 54% of state agencies had direct access, and only 1% of local and county agencies had direct access (page 27).

In the section beginning on page 30 titled “FinCEN Lacks Written Policies and Procedures to Help Ensure That Agencies without Direct Access Use BSA Reports to the Greatest Extent Possible” were the following observations:

- “Thirty-two state attorney general offices, including offices that prosecute criminal cases involving money laundering, such as organized crime, public corruption, and human trafficking, did not have direct access” To the FinCEN database.

- “Twenty-one of the 50 largest local police departments, which investigate crimes that could involve money laundering, such as drug trafficking, financial crimes, cybercrimes, terrorism, and human trafficking, did not have direct access” to the FinCEN database.

The GAO noted (page 32) that FinCEN “scores” law enforcement agencies seeking direct access, and that it denied 40 of 103 applications from 2015 through 2018. In addition to gaining direct access to the BSA database, law enforcement agencies can request searches. But in 2018, only 4% to 8% of the roughly 15,000 state and local police departments requested searches. The GAO wrote “[a]ccording to FinCEN officials, they do not have policies and procedures to promote the use of BSA reports to law enforcement agencies without direct access.” But FinCEN disputed this finding in its response (see Appendix VII, page 194).

FinCEN Disseminating Information to Law Enforcement

As set out above, 31 USC section 310(b)(2)(B) – (E) set out the duties and powers of the Director of FinCEN. The GAO describes these at page 34 as requiring FinCEN to disseminate BSA reports to identify possible criminal activity to appropriate federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement agencies.

In other words, in addition to opening up its BSA database, FinCEN has a duty to “analyze and disseminate the available data” to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. The GAO found (at page 34) that “FinCEN’s written policies and procedures do not specifically address how to achieve that outcome.”

It appears that FinCEN could do more to proactively reach out to law enforcement. This is another area of opportunity for FinCEN. As the country’s financial intelligence unit, or FIU, it has the duty and responsibility to provide actionable intelligence to law enforcement – to disseminate information to law enforcement. It is, and should be, more than a financial information depository organization.

Issue 2 – The BSA/AML Compliance Cost Burden

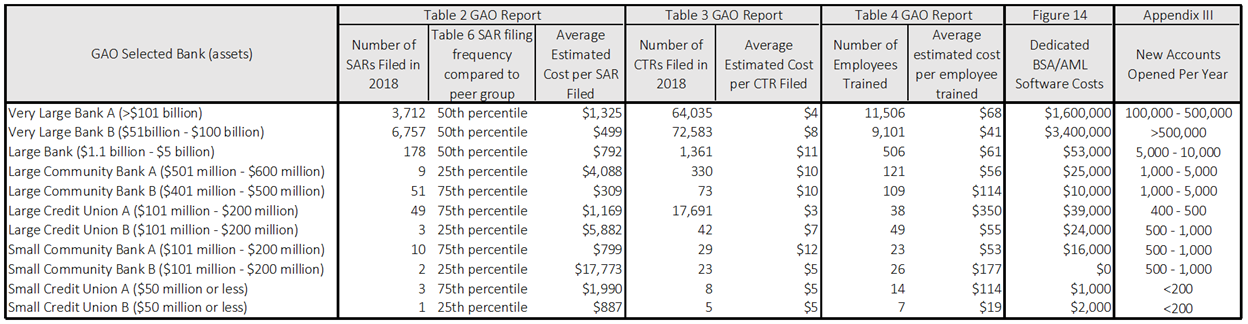

The GAO included a representative sample of four credit unions and seven banks.[6] The key attributes of the eleven surveyed financial institutions are in Appendix III. I summarized multiple tables containing the details of the eleven institutions into one table:

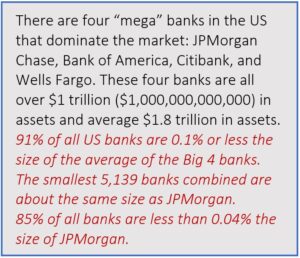

Some observations on US banks and credit unions are warranted in order to put these eleven institutions in some sort of context. I will use data from roughly the time these institutions were selected.

- There are 4 banks with assets of $1 trillion or more. These four banks have a total of $7.2 trillion in assets. The other 5,367 banks have combined assets of $11 trillion.

- The next 40 largest banks assets between $50 billion and $500 billion. The two “Very Large Banks” in this report are on the small end of that range.

- There are 188 banks with assets between $5 billion and $50 billion.

The “Large Bank” in this report is at the small end of that range.

The “Large Bank” in this report is at the small end of that range. - The majority of US banks – 2,847 or 53% – have assets less than $250 million. The two “Small Community Banks” in this report are in the middle of this range.

- Of the ~5,200 credit unions, only 7 of then have assets of more than $10 billion, and the largest, Navy Federal Credit Union, is less than $100 billion in assets.

I found it curious, and could not find an explanation, that the “Large Credit Unions” were both smaller than $200 million in assets: there are more than 300 credit unions that have more than $1 billion in assets. It would have been instructive to have one of these larger credit unions and even one of the seven of the largest credit unions.

Also, the GAO was careful not to select a bank or credit union that was under spending duress from a recent enforcement action (“we used information from the federal banking agencies to confirm that the banks we selected were not subject to BSA/AML-related formal enforcement actions in recent years”). Also notable, the GAO “did not assess the quality of banks’ BSA/AML programs.” (footnote 88, page 36).

The GAO considered the overall direct costs of running a BSA/AML program, as well as breaking out those costs into five main components of a BSA/AML program: customer due diligence, reporting, the four pillars, software and consultants, and a catch-all “other” made up of monetary instrument reporting, funds transfer recordkeeping, information sharing, and special measures.

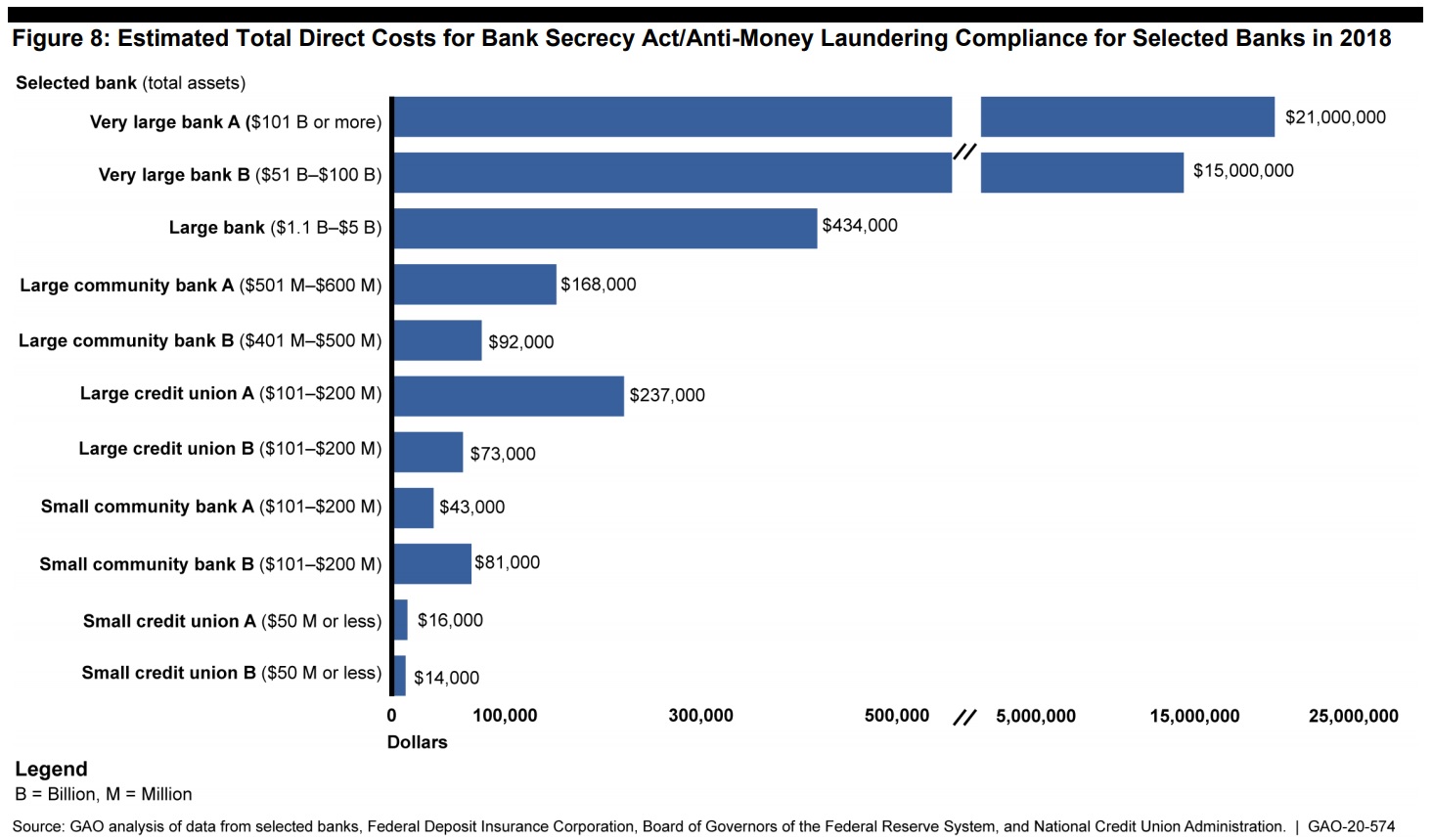

Estimated Total Direct Costs for BSA/AML Compliance Programs

Figure 8 summarizes the estimate direct costs for each of the eleven banks. “Direct” costs were defined as labor, software, and third party costs, and did not include indirect costs such as office space or depreciation on computer systems. The GAO noted that the estimate for Very Large Bank B, based on interviews, surveys, and reviewing budget documents, of $15 million was comparable to the actual budget of the bank’s BSA/AML Department of $13 million.

The GAO also included seven other recent (2016-2018) cost of compliance studies in Appendix IV of the Report. It noted that a 2018 Bank Policy Institute survey of fourteen large banks found that the median program costs for banks in the $50 billion to $200 billion range was $25 million, and the median program costs for the mega banks (those with assets over $500 billion) was $600 million.

I observed (and describe below) that the average cost per SAR of the largest bank in this survey (roughly $100), extrapolated out to the 150,000 SARs the four mega banks file (on average) would result in SAR filing costs alone of $150 million. This Report also suggests that SAR filing accounts for 25% of total program costs, meaning the four mega banks would have total program costs of $600 million. This aligns with the BPI survey.[7]

Estimated Direct Costs by BSA Program Component

Figure 10 on page 41 breaks out the relative costs for the five main program components. What is clear is that Customer Due Diligence (CDD) requirements and BSA reporting – primarily SAR reporting – make up the majority of the program costs.

All the credit unions and the two small community banks opened less than 1,000 new customer relationships in 2018. The smallest institutions had very manual CDD processes, thus relatively higher costs, and the larger institutions had more automated processes, thus relatively lower costs. The larger banks all had more automated processes: sheer volumes of new customers, and the complexities of those customers, contributed to the higher relative costs.

Cost of Customer Due Diligence

The analysis of the cost of customer due diligence began at page 42. The GAO noted “For the 11 banks in our review, estimated costs for complying with the customer due diligence requirements ranged from about 15 percent to about 59 percent of total direct BSA/AML costs. These requirements collectively were more costly than any other BSA/AML requirement (as a percentage of total costs) for five of the 11 banks, including the four largest.”

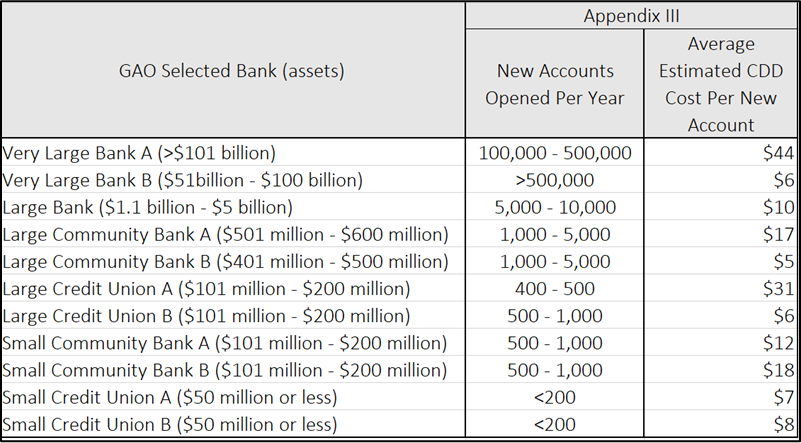

The per-account costs seemed low to me. Table 1 showed that the selected banks spent an estimated average of $15 per new account to comply with the customer due diligence requirements in 2018, and per-account costs ranged from $5 to $44. That table is summarized here.

As a general rule, legal entity customers take longer to onboard than natural persons. Small Credit Union B, which opened up less than 200 accounts at a cost of $8 per account, opened only one account in 2018 for a legal entity. It’s average cost per new account was $8. Very Large Bank A, on the other hand, opened over 36,000 legal entity accounts in 2018 at a total cost of ~$3.7 million or $103 per legal entity account. Using a fully-loaded cost of $75,000 and 1,720 effective hours in a year gives an hourly rate of $43.60. That would suggest that this Very Large Bank took about 2.5 hours to onboard a legal entity customer.

Implementation Costs of the Beneficial Ownership Requirement

Page 43 of the Report had an interesting sidebar. It provided:

The 11 banks we studied also incurred onetime implementation costs to comply with the new beneficial ownership requirement for legal entity customers, which has an applicability date of May 11, 2018, as part of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s final rule on Customer Due Diligence Requirements for Financial Institutions.

Banks we reviewed incurred costs to research the new requirement, update policies and procedures, revise information collection systems, and train personnel. However, implementation costs varied. For example:

-

- Small credit union B ($50 million or less in total assets), which opened only one legal entity account in 2018, spent under $100 to implement the new requirement, including to update policies and train personnel.

- Very large bank A ($101 billion or more in total assets), which opened over 36,000 legal entity accounts in 2018, spent an estimated $3.7 million. Bank representatives told us that they assigned two senior compliance personnel to the implementation project over a 2-year period, updated hardware and software systems, and trained approximately 4,000 bank personnel on the new requirement.

Cost of Suspicious Activity Reports

The GAO looked at the costs of all BSA reports: SARs, CTRs, and others (CMIRs, FBARs, DOEPs). All of these reports together accounted for an average of 28% of the total cost of running a BSA/AML program, but the SAR-related costs accounted for 90% of the total reporting costs. They also noted that the bulk of the SAR costs – 83% – were incurred in monitoring for and investigating suspicious activity alerts. They described “investigating” as includes the time banks spent initially reviewing an alert, escalating it to an investigation, and deciding whether to file a SAR, so it appears that the other 17% of the costs related to preparing and filing the actual SAR, as well as the long-term recordkeeping requirements.

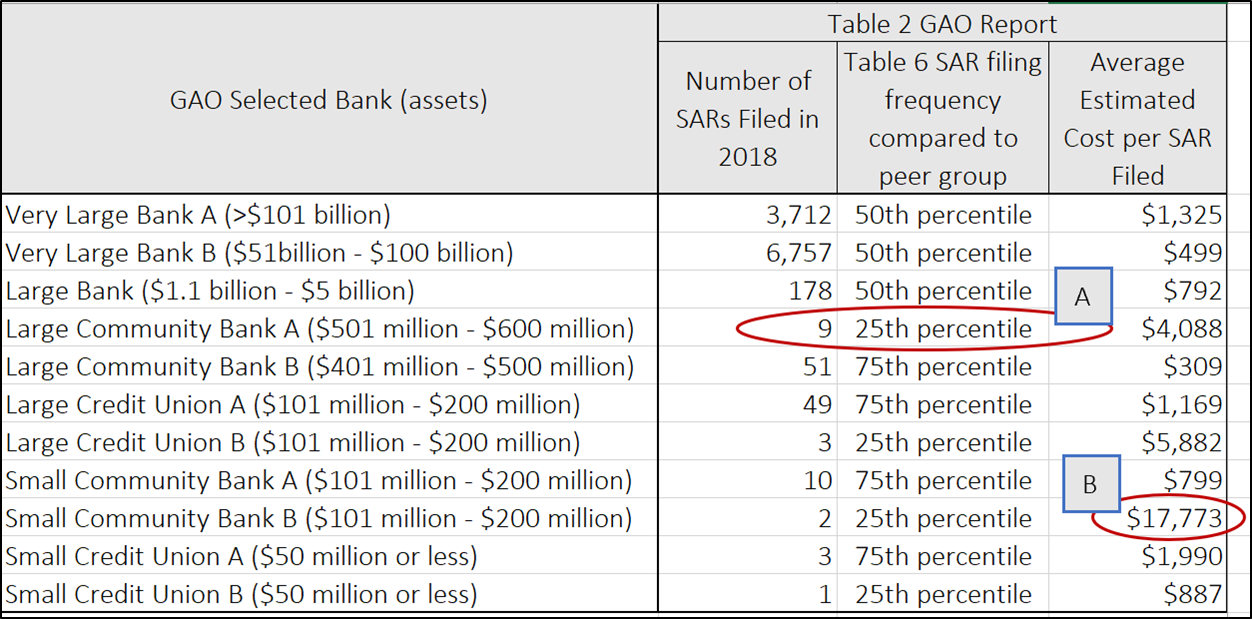

Table 2 on page 47 of the Report provides the number of SARs, and average estimated cost per SAR filed, for the eleven financial institutions. I added a third column for the institution’s SAR filing frequency compared to its peer institutions.

I have two observations from Table 2. Observation A relates to Large Community Bank A that only filed 9 SARs in 2018 (putting it in the bottom quarter in number of SARs filed within its peer group). The Report notes that this bank reported that it generated 7,000 Alerts that resulted in 60 Cases that generated 9 SARs. That is a Alert/SAR ratio of 0.13%, or a false positive rate of 99.87%.

The second observation (B) relates to Small Community Bank B, also in the bottom 25% in number of SARs filed in its peer group. That bank filed two SARs. It reported that both related to elder financial abuse and both took about 80 hours to investigate and report. $17,691 divided by 160 hours is $110.57 per hour, suggesting that more senior people were involved in the SAR in investigation.

GAO’s Survey and FinCEN’s SAR Burden and Cost Estimate

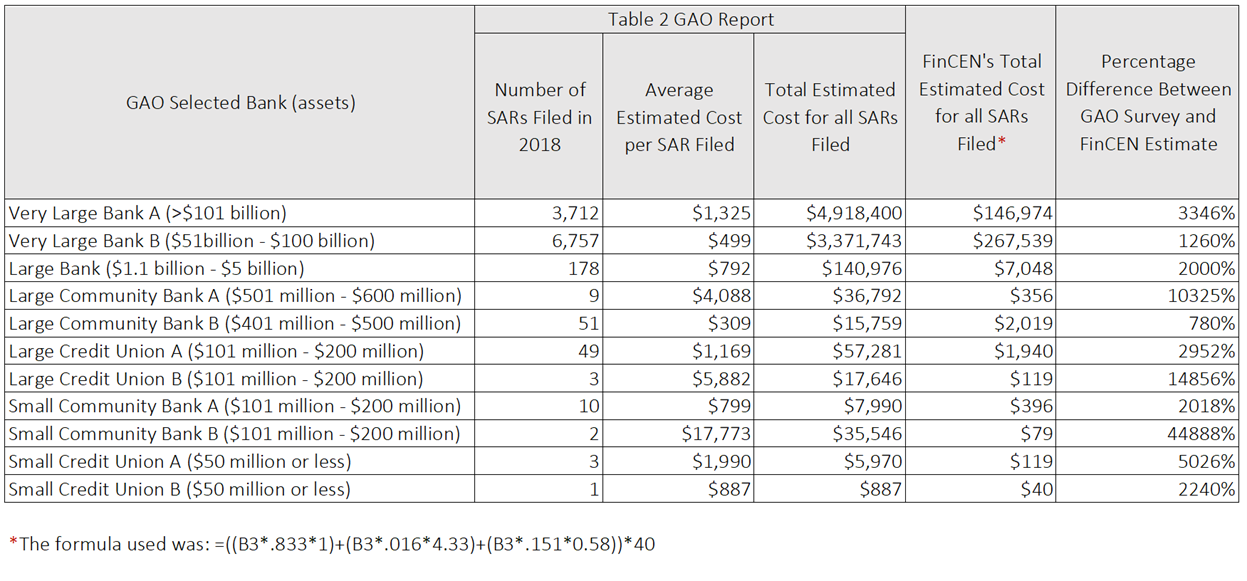

The third observation needs me to pull in a SAR cost and burden estimate that was recently published by FinCEN. Recall that earlier this year (May 26, 2020) FinCEN published a request for comments on its estimates of the costs and burden of filing SARs. Whereas the GAO considered the total SAR process – monitoring, the initial review of alert, escalating alerts to “case” (to an investigation), conducting the investigation, making the SAR/No SAR decision, preparing and filing the actual SAR, and the long-term recordkeeping requirements – FinCEN’s analysis only considered the process from the “case” forward: conducting the investigation, making the SAR/No SAR decision, preparing and filing the actual SAR, and the long-term recordkeeping requirements. FinCEN concluded that “simple” SARs (about 83% of all SARs) took between 45 and 75 minutes each; “complex” SARs (about 2% of all SARs) took between 205 and 315 minutes; and “Continuing activity” SARs (about 15% of all SARs) took between 25 and 45 minutes.[8]

So I compared FinCEN’s estimates with what the GAO found. The results are interesting.

First, I used a fully-loaded cost of $75,000 per full time equivalent (FTE) and 1,720 effective hours in a year to get an hourly rate of $43.60. For mathematical simplicity, I reduced that to $40 per hour. Second, I took the average time for each of the three types of SARs that FinCEN identified:

- Simple SARs: 83.3% of SARs taking 45 to 75 minutes each = 60 minutes, or 1.0 hour

- Complex SARs: 1.6% of SARs taking 205 to 315 minutes each = 260 minutes or 4.33 hours

- Repeat SARs: 15.1 % of SARs taking 24 to 45 minutes each = 35 minutes or 0.58 hours

As can be seen, the GAO survey results were very different than the FinCEN estimates. The biggest reason is that the GAO results included the costs of generating alerts and dispositioning the alerts – either deciding to open a case and conduct and investigation, or close the alert without doing an investigation. Recall my observation on Large Community Bank A, that had 7,000 alerts but only 60 cases and 9 SARs. The GAO survey included the cost of making determination on 6,940 alerts that did not result in a case investigation, and 51 investigations did not result in a SAR. The FinCEN methodology only considered the costs of the case investigations and SARs. And Small Community Bank B, where FinCEN’s methodology was 45,000 percent less than the GAO survey, reflects the fact that each of those two SARs took that bank 80 hours (they were elder financial exploitation cases, which are always very time intensive).

This is not a criticism of FinCEN’s methodology, but a call for a more fulsome analysis of all the aspects of suspicious activity monitoring, alert generation, alert disposition, case management, investigations, SAR decisions, preparation, filing, recordkeeping, and responding to law enforcement requests for supporting documentation.

Proposed Changes to the SAR Threshold

Part IV of the Report, beginning on page 68, includes a section on whether to increase the SAR reporting threshold from $5,000 to $10,000. I’m including a summary of that section here, for continuity purposes.

The GAO noted that there have been Congressional efforts (bills) to increase the mandatory SAR filing threshold from $5,000 – first set in 1996 – to $10,000.[9] The result, according to an analysis by FinCEN, would be 21% fewer SARs filed by depository financial institutions (banks and credit unions).

How many SARs is 21%? Using FinCEN’s SAR Stats – https://www.fincen.gov/reports/sar-stats – for calendar year 2018 (which the GAO was using for its Report), based on the primary federal regulator, we find:

118,113 SARs filed by Credit Unions (NCUA regulated entities)

859,590 SARs filed by Banks (FDIC, FRB, OCC)

873,479 SARs filed by Money Services Businesses (IRS)

319,991 SARs filed by All Others (multiple regulators)

2,171,173 Total SARs filed in 2018

Law enforcement disagreed with increasing the mandatory SAR reporting threshold: “Officials from six federal law enforcement agencies expressed concerns that raising the SAR threshold, as with the CTR threshold, would reduce the amount of financial intelligence available to law enforcement agencies and harm their investigations … Officials said that the nature of the suspicious activity, such as human trafficking and terrorist financing, can be more relevant than the amount of money involved.” (page 68). I agree. And so do many banks: according to this Report, banks filed ~44,000 SARs reporting amounts less than $5,000, roughly 5% of all bank SARs filed in 2018.

In addition, law enforcement found SARs to provide a high degree of usefulness: at page 69 it is noted that 53% of the law enforcement agents used SARs frequently, and 50% found them to be very useful.[10]

There was also a discussion on streamlining SAR filings for structuring.[11] In footnote 137 on page 70, the GAO described structuring as follows:

According to FinCEN, structuring can take two basic forms. First, a customer might deposit currency on multiple days in amounts under $10,000 for the intended purpose of circumventing a bank’s obligation to report any cash deposit over $10,000 on a CTR. Although such deposits do not require aggregation for currency transaction reporting because they occur on different business days, they nonetheless meet the definition of structuring under the BSA, implementing regulations, and relevant case law. In another variation, a customer may engage in multiple transactions during 1 day or over a period of several days or more, in one or more branches of a bank, in a manner intended to circumvent either the currency transaction reporting requirement or some other BSA requirement, such as the recordkeeping requirements for funds transfers of $3,000 or more.

This description makes structuring seem like an easy thing to detect, alert on, investigate, and report. It isn’t, or, rather, the variations of structuring are not always easy to detect, alert on, properly and thoroughly investigate, and accurately report. There are often multiple parties, co-signers, non-accountholder depositors involved in multiple, related transactions; there can be multiple branches, ATM deposits, or cash vault deposits made in multiple (but somehow related) accounts. Very few structuring cases involve one customer with one account and one branch over a one- or two-day period. Banks and industry groups have suggested “auto-filing” “simple structuring” SARs or reducing or eliminating the narrative portion for structuring SARs. Law enforcement does not support either initiative.

Sharing SARs With Foreign Branches

There is a quirk in the regulations and regulatory guidance around the sharing of SARs, or information that would lead to the discovery of a SAR, with the foreign branches of a US financial institution. The discussion begins on page 71 of the Report. Notably, only 34 banks, out of the 5,250 banks in the US at the time of the Report, have one or more foreign branches (in 65 countries), so this issue is limited to only a few of the largest, most complex, international financial institutions. The issue is complex, but can be summarized as follows:

- A US branch of a foreign bank may disclose a SAR to its head office outside the United States

- A US bank may not disclose a SAR to its branch offices outside the United States

The GAO, and FinCEN, and the private sector, all agree that greater clarity and consistency is required, particularly given the international nature of many transactions, if not financial institution structures.

Cost of Currency Transaction Reports

At page 49 the GAO noted “banks generally must file a CTR when a customer conducts a transaction in currency of more than $10,000 in aggregate over 1 day.”

If it was only that simple. The 2014 edition of the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual devotes a page to explaining the CTR requirement:

A bank must electronically file a Currency Transaction Report (CTR) for each transaction in currency (deposit, withdrawal, exchange, or other payment or transfer) of more than $10,000 by, through, or to the bank. Certain types of currency transactions need not be reported, such as those involving “exempt persons,” a group which can include retail or commercial customers meeting specific criteria for exemption …

Aggregation of Currency Transactions

Multiple currency transactions totaling more than $10,000 during any one business day are treated as a single transaction if the bank has knowledge that they are by or on behalf of the same person. Transactions throughout the bank should be aggregated when determining multiple transactions.

In cases where multiple businesses share a common owner, the presumption is that separately incorporated entities are independent persons. The currency transactions of separately incorporated businesses should not automatically be aggregated as being on behalf of any one person simply because those businesses are owned by the same person. Financial institutions should determine, based on information obtained in the ordinary course of business, whether multiple businesses that share a common owner are being operated independently depending on all the facts and circumstances.

However, if a financial institution determines that these businesses (or one or more of the businesses and the private accounts of the owner) are not operating separately or independently of one another or their common owner (e.g., the businesses are staffed by the same employees and are located at the same address, the bank accounts of one business are repeatedly used to pay the expenses of another business, or the business bank accounts are repeatedly used to pay the personal expenses of the owner) the financial institution may determine that aggregating the businesses’ transactions is appropriate because the transactions were made on behalf of a single person.

If a financial institution determines that the businesses are independent, then it should not aggregate the separate transactions of these businesses. Alternatively, once a financial institution determines that the businesses are not independent of each other or their common owner, then the transactions of these businesses should be aggregated going forward. (2014 Exam Manual, page 82, three footnotes omitted)

The paragraph that describes the complexities of CTRs is “multiple currency transactions totaling more than $10,000 during any one business day are treated as a single transaction if the bank has knowledge that they are by or on behalf of the same person. Transactions throughout the bank should be aggregated when determining multiple transactions.” This same paragraph is the source of the wide range in regulatory expectations across the industry, as some institutions do not have the systems or other capabilities (they lack knowledge) to aggregate across conductors, across accounts, across delivery channels. The Exam Manual instructs examiners to “determine whether the bank aggregates all or some currency transactions within the bank.” (page 87). But not all institutions can, nor do all examiners expect their institutions to, identify and aggregate all cash transactions conducted at bank branches, cash vaults (and those can be outsourced to other institutions), ATMs, and even mail-in services. As a result, determining who is conducting the cash transaction(s), on whose behalf the transaction(s) are being done, through which delivery channel(s), can be so daunting for smaller institutions that they don’t do it, and their regulators don’t expect them to do it.

I expect that the low time and cost estimates in this Report are a result, in part, of a lack of identification of all conductors, beneficiaries, and delivery channels. The GAO estimated that the costs to identify, research, complete, and file a CTR ranged from about $3 to about $12 (or about $7 on average) for the 11 banks.

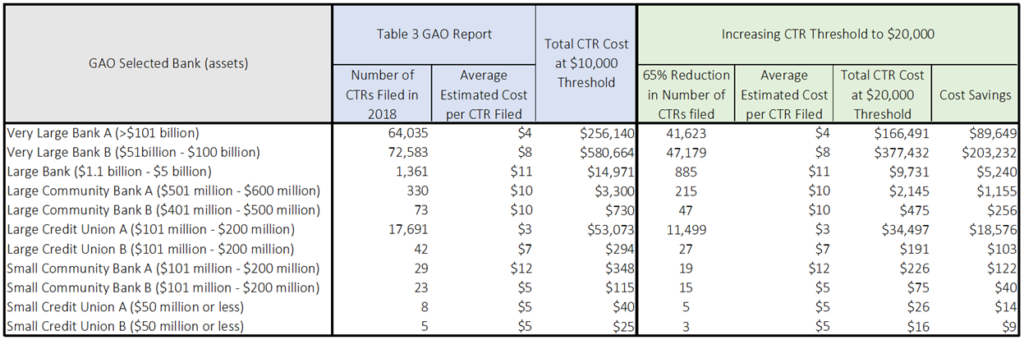

Proposed Changes to the CTR Threshold

The Report considered the impact of increasing the CTR threshold (pages 65-67). Increasing the CTR threshold has been the most common, and in my opinion least understood, proposal to reduce banks’ BSA compliance burdens. Proponents of increasing the threshold commonly point out that the

$10,000 threshold was set when the BSA was first enacted in 1970. As the GAO notes:

FinCEN’s analysis indicates that … increasing the CTR threshold from $10,000 to $20,000 would have resulted in banks filing around 65 percent fewer CTRs. Increasing the threshold to $30,000 would have resulted in banks filing around 81 percent fewer CTRs. Finally, increasing the threshold to $61,276 (original 1970 threshold adjusted for inflation) would have resulted in banks filing around 94 percent fewer CTRs.

As with the arguments for raising the SAR threshold to account for inflation, these arguments are misguided and ill-informed. First, the original 1970 threshold of $10,000 was for a single cash transaction: there was no aggregation. Second, that threshold was established before ATMs, before credit cards, before mobile or online or other electronic banking. I argue that single cash transactions of $5,000 are even rarer or more unusual today than cash transactions of $10,000 were twenty, thirty, or forty years ago. Multiple Federal Reserve studies show that the average cash transaction is less than $20, and the median cash transaction is $2 – $3. A more effective way to reduce overall compliance costs is to simplify the CTR reporting requirement to single cash transactions greater than $10,000 (allowing for fully automated reporting), leaving all other aggregated cash transactions and the “by or on behalf of” identification and analysis to the Suspicious Activity Report.

I agree with law enforcement’s opposition to raising the CTR threshold:

Officials from six federal law enforcement agencies told us that they generally oppose raising the CTR threshold, largely because it would reduce the amount of financial intelligence available to them for investigations, analysis, and prosecutions. For example, fewer CTRs could reduce opportunities for law enforcement to link financial transactions to criminal activity and identify subjects, coconspirators, and assets related to ongoing investigations. Officials also said that increasing the CTR threshold would make it easier for criminals to launder greater amounts of illicit proceeds. Further, officials told us the $10,000 threshold may continue to be warranted because, as customers have shifted to electronic payments, large cash transactions may especially signal potentially suspicious activity. Finally, some officials said that law enforcement has used lower-dollar CTRs to investigate terrorism, fraud, and money laundering. (pages 66-67)

The GAO noted that five of the six industry associations that they interviewed generally supported increasing the CTR reporting threshold to reduce costs. But what costs would be reduced? I used the GAO data on the number of CTRs filed and average estimated costs, then reduced the number of CTRs filed by 65% (FinCEN’s estimated reduction in CTRs by moving the threshold to $20,000).

The result is that increasing the CTR threshold from $10,000 to $20,000 would materially reduce the compliance costs for only the largest banks: even the “Large Bank” would see its total compliance costs go down by only $5,240. Given that 42% of law enforcement uses CTRs frequently, 39% of them find CTRs very useful, and some of the most egregious crimes – human trafficking and terrorist financing – involve very small dollar amounts, these cost savings are not worth the potential human costs. I recommend that the $10,000 CTR threshold remain.

Cost of Managing Three (of Four (or Five?)) Pillars of a BSA/AML Program

There are four (or five) pillars to a BSA/AML program: a system of internal controls, a designated BSA compliance officer, independent testing (audit), and training.[12] The GAO considered the BSA compliance officer costs to be embedded in the other components of a program (CDD, reporting, training, etc., so did not consider those costs separately. The GAO described internal controls as the policies, procedures, and processes banks use to manage risks and ensure compliance (pages 51-52). They considered the costs of updating policies, procedures, and processes and conducting a risk assessment, and concluded that the two very large banks spent $200,000 and $500,000, while the average of all the others was $1,800.

In multiple parts of the Report the GAO cautioned that their findings for these eleven banks cannot be generalized to other banks (see, for example, page 40). After seeing the results for the costs attributed to the system of internal controls, I agree. It is inconceivable to me that any financial institution in the United States, no matter how small, can spend $220 in personnel time to develop, maintain, update, and implement BSA/AML policies, procedures, and processes AND conduct an annual and ongoing risk assessments to ensure those controls are appropriately risk-based. $220 is between 1 and 5 hours of time, depending on the position. It is simply not possible to run an effective, even adequate program for a year by dedicating 1 to 5 hours. In fairness, the GAO did not consider the effectiveness of any of the banks and credit unions it surveyed.

One thing did emerge from the data that may be worth commenting on. The two large credit unions indicated they spent $183 and $297 on their system of internal controls. Their two bank peers – the two large community banks – indicated they spend $3,232 and $4,379, or roughly fifteen times what the two credit unions spent. The GAO may consider an audit of the relative supervisory programs of the NCUA and FDIC.[13]

Cost of AML Software

I combined Tables 2 and 6 with Figure 14 to show the number of SAR filed, the average estimated cost per SAR filed (employee time), and the dedicated BSA/AML software costs (which are in addition to the estimated cost per SAR filed). The GAO noted that 10 of the 11 banks that used specialized software used it to assist with customer due diligence requirements, such as verifying customers’ identities and assigning risk profiles to their accounts. Eight of the 10 banks used surveillance monitoring software to identify suspicious activity. What this chart suggests is that transaction monitoring and customer surveillance monitoring and alerting systems, and case management systems to manage the investigative processes, are the most costly.

In an interesting section on pages 59-60 dealing with whether banks passed on their BSA/AML costs to their customers (they generally did not), the GAO noted that “at least six of the banks said they did not offer accounts to money services businesses because of the potentially greater and more costly due diligence, monitoring, and reporting involved.”

Issue 3 – Supervision/Examination of BSA Compliance Program

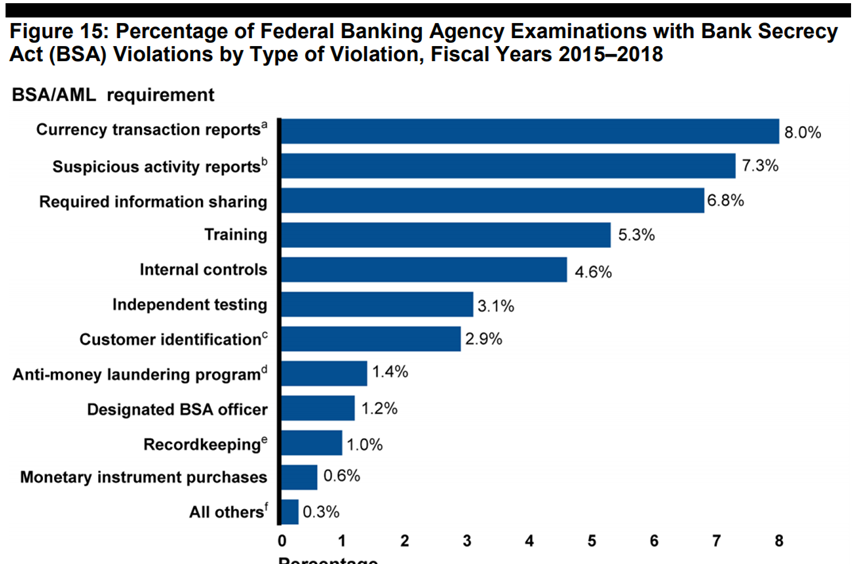

The GAO chose to use this statement as their sidebar/headline introducing this section of the Report on page 60: “Federal Banking Agencies Are Required to Conduct BSA Compliance Examinations and Cited Nearly a Quarter of Banks Under Their Supervision for BSA Violations”. That is an accurate, but deceptive statement. Two pages later, in another sidebar, the GAO wrote: “FinCEN Data Show Nearly a Quarter of the Examined Banks Had BSA Violations, but Many Violations Were Technical.” And then two pages later, in the last paragraph of this section on page 64, the GAO wrote that “the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC issued 123 BSA-related formal enforcement actions in fiscal years 2015–2018 – representing less than 1 percent of the total BSA examinations that they conducted during the same period.

This is unfortunate, as the message from the headline – a quarter of all banks are violating the BSA – is different from the reality – although a quarter of banks have technical violations of the BSA, less than 1 percent have substantive violations requiring formal enforcement actions.

Figure 15 (page 63) of the Report sets out the percentage of federal banking agency exams with BSA violations, by type of violation. As can be seen in the chart below, the most common type of violation was CTR (8.0%) then SAR (7.3%). Notably, an overall program violation was cited in only 1.4% of the exams, and those program violations resulted in public enforcement actions in less than 1 percent of the exams. This is clear evidence that the vast majority of banks and credit unions are taking their BSA/AML responsibilities seriously, and doing a good job.

US Attorneys’ Annual Statistical Report for Fiscal Year 2019

This statistical report is not part of the GAO Report. The DOJ statistical reports are available going back to fiscal year 1955 (the federal government’s fiscal year ends on September 30th). They are available at https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/annual-statistical-reports.

The reports provide an incredible amount of information on federal criminal cases by US Attorney’s office, by major type of criminal offence, by number of cases filed and completed, how they are completed (guilty, not guilty, dismissed, other), whether dispositioned in district court or by magistrate, length of case, etc.

Why is this important? The GAO report tells us that in 2018 banks and credit unions filed about 1 million SARs and 14 million CTRs. The GAO report also tells us that six major federal law enforcement agencies – DEA, FBI, HIS, IRS-CI, USAOs, and USSS – have almost 29,000 investigators, 8,000 analysts, and 5,300 prosecutors. That 53 percent of them used SARs frequently, and 50 percent found them very useful. That 59 percent of them used BSA reports to start or assist new investigations and 72 percent used them to conduct or assist in ongoing investigations. That 41 percent of them used BSA reports to analyze trends or patterns, and 44 percent used them to work on criminal prosecutions. That 74 percent of them used BSA reports in potential drug trafficking prosecutions, and 27 percent used them in potential human trafficking prosecutions. But the GAO Report doesn’t tell us how many criminal prosecutions there were. The US Attorney’s Statistical Report tells us.

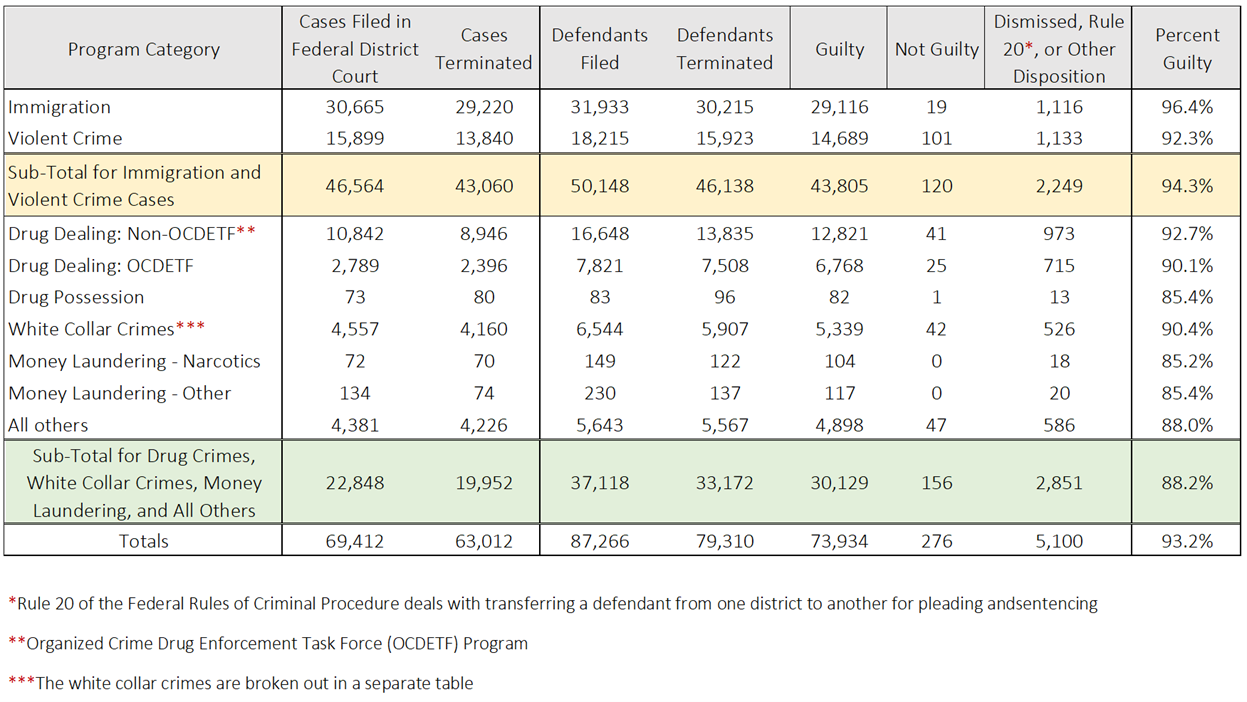

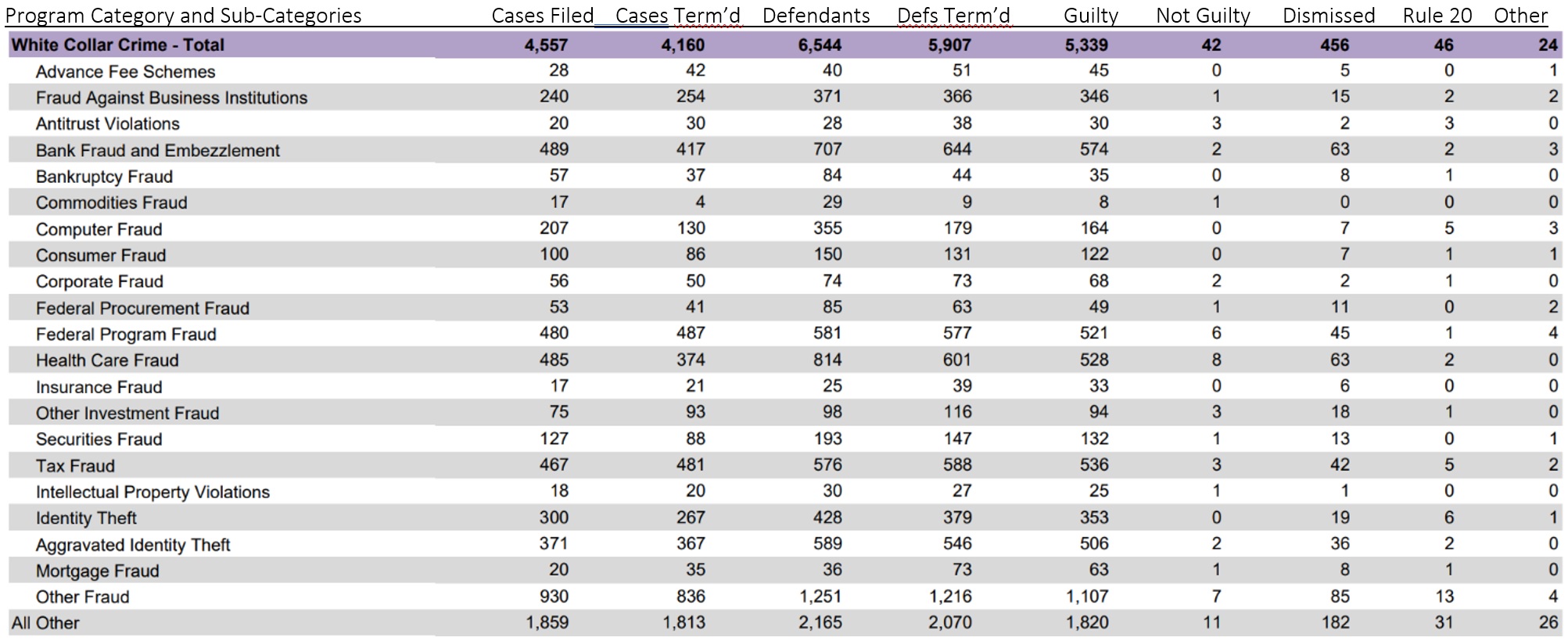

Each of the program categories has a number of crimes. The table below summarizes a four-page table from the US Attorneys’ Statistical Report. It shows that in fiscal year 2019 (October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019), there were a total of 69,412 cases filed in Federal District Court naming 87,266 defendants. 63,012 cases involving 79,310 defendants were terminated: 73,934 defendants, or 93.2% pled or were found guilty (0.3% were found not guilty).

I chose to differentiate the Immigration and Violent Crime program categories from all other federal criminal program categories. I made the assumption that BSA reports were not likely to have been utilized in immigration or violent crime cases. This leaves 22,848 federal criminal cases that were brought in fiscal year 2019 that law enforcement likely, or could have, used BSA reports.

Recall Figure 6 on page 4 of this document, which summarized ten tables of data (Tables 0-89) from pages 149-156 of the GAO Report, where the GAO asked law enforcement which potential criminal activities they used BSA reports. Figure 6 showed that 74% of law enforcement agents indicated they used BSA reports for potential drug trafficking. Here, we can see that 13,631 “drug dealing” cases were filed in FY2019.

Looking at the data, and the issues, at their most basic level, we have 20 million BSA reports and something less than 25,000 federal criminal cases where those reports could have been useful. Even assuming that 100% of the 25,000 federal criminal cases used BSA reports (and law enforcement indicated that only half of them used SARs and CTRs frequently and found them very useful), we don’t know which reports were used for what purposes in what types of cases.

As the GAO noted on page 35 of their Report: “systematically collecting information on outcomes from use of BSA reports is essential to understanding the value of the program and a critical step toward streamlining and improving the program for the future.”

The “White Collar Crimes” category of crimes is interesting, as it closely reflects many of the categories set out in the Suspicious Activity Report form itself.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The first conclusion is that about half of federal law enforcement agents frequently use SARs and CTRs, and find them very useful. This means that half don’t use them, or if they do, don’t find them very useful. So there is room for improvement. And this overall, or average, usage/usefulness isn’t reflected in all criminal investigations: BSA reports are used in about one of every four human smuggling and human trafficking investigations. I recommend that FinCEN mount a concerted effort to target those agencies that are not using SARs and CTRs frequently, as well as work with those agencies focused on human smuggling and human trafficking investigations.

The second conclusion tracks the GAO recommendation: FinCEN needs to do more to give state and local/county law enforcement agencies access to the FinCEN BSA database and do what they can to ensure those agencies are using the BSA reports. According to the GAO, only 54% of state agencies and 1% of local and county agencies have direct access to the FinCEN BSA database.

The third conclusion is that FinCEN does not have the resources to analyze and disseminate information, intelligence, and BSA reports out to state and local law enforcement agencies. The GAO found that about 1% of 15,000 state and local law enforcement agencies had direct access to the BSA database, but as I wrote on page 6, FinCEN is to monitor and disseminate: 31 U.S.C. § 310(b)(2)(C) provides that the FinCEN Director is empowered to “analyze and disseminate the available data in accordance with applicable legal requirements and policies and guidelines established by the Secretary of the Treasury and the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Enforcement to– (i) identify possible criminal activity to appropriate Federal, State, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies …”. Congress needs to fund FinCEN appropriately so it can really be a true financial intelligence unit (rather than a financial information depository organization) by analyzing and disseminating more actionable intelligence to all law enforcement agencies.

It is difficult to draw any conclusions on the second issue, the cost of BSA compliance. Indeed, the GAO warns us against drawing any conclusions: they indicated on a number of occasions that the information they obtained from the eleven banks in their sample “cannot be generalized to other banks”. That appears to be a fair warning. Any conclusions for the overall BSA/AML/CFT regime should only be drawn if and when the GAO conducts similar audits of the un- or under-represented parts of the private sector participants. I suggest two audits: one of the four mega banks, which account for about half of all SARs and CTRs filed by all 10,000+ banks and credit unions (collectively, “depository institutions” in FinCEN’s reporting methodology); and Money Services Businesses, or MSBs, which file almost as many SARs as depository institutions (and the MSB industry is as dominated by two large institutions, Western Union and MoneyGram, as depository institutions are dominated by the big four).

One conclusion, and recommendation I will make, though, relates to the differences between the cost estimates that the GAO found from its limited survey of eleven banks and credit unions, and FinCEN’s May 26, 2020 estimates of the burden and costs of part of the SAR process. From these differences it is easy to conclude, and recommend, that any future estimate of the SAR burden and cost that FinCEN publishes must include the entire SAR process: from suspicious activity monitoring, to alert generation, to alert disposition, case management, investigations, SAR decisions, preparation, filing, recordkeeping, responding to law enforcement requests for supporting documentation, and the internal testing and auditing, and external examinations of, that process.

As to the third issue, the supervision and examination of BSA compliance, I recommend that the BSAAG provide guidance to the private sector and regulatory agencies on how to better position the private sector’s overall compliance with BSA/AML laws, regulations, and regulatory guidance. This is particularly important with so much media, political, and social pressure on parts of the industry as a result of the FinCEN Files. As the GAO report found, less than 1% of BSA examinations result in enforcement actions, which means more than 99% of BSA examinations conclude that the financial institution is generally meeting its regulatory obligations. That story is not being told well.

We also need to put to rest the inane and ill-informed notions of raising the mandatory CTR and SAR filing thresholds. According to the GAO report – which we apparently should not rely on – CTRs don’t cost very much, so any percentage savings wouldn’t be enough to offset the loss of intelligence to law enforcement. And the amount being reported doesn’t create complexity and cost: it is the aggregation of multiple transactions across multiple delivery channels and the “by and on behalf of” requirements. The better solution is to keep the threshold at more than $10,000, make it a single transaction reporting the accountholder … and everything else (aggregation, conductors, different channels, etc.) moves to a determination of whether the activity was suspicious. And raising the mandatory SAR threshold from $5,000 to $10,000 won’t address the fundamental problem: we don’t know which SARs law enforcement finds useful.

Tactical or Strategic Value (TSV) SARs

The GAO described what needs to be done to reform the AML regime. At page 35 of their Report:

Systematically collecting information on outcomes from the use of BSA reports is essential to understanding the value of the program and a critical step toward streamlining and improving the program for the future.

So that is what needs to be done. But how can we systematically collect information on outcomes from the use of BSA reports? And if the purpose of the BSA/AML regime is to produce reports that have a high degree of usefulness to government agencies, how do we identify and measure what is useful?

I’ll begin to answer those questions by posing another question: should private sector SARs that cost billions of dollars to produce be “free” to public sector law enforcement agencies? Put another way, should the public sector law enforcement agency consumers of SARs need to provide something in return to the private sector producers of SARs?

I say they should. And here’s what I propose: that in return for the privilege of accessing and using private sector SARs, law enforcement should have to pay for that privilege. Not with money, but with effort. The public sector consumers of SARs should be required to notify the private sector producers which of those SARs provide tactical or strategic value.

A 2018 Mid-Size Bank Coalition of America (MBCA) survey found the average MBCA bank had 9,648,000 transactions/month being monitored, resulting in 3,908 alerts/month (0.04% of transactions alerted), resulting in 348 cases being opened (8.9% of alerts became a case), resulting in 108 SARs being filed (31% of cases or 2.8% of alerts). The MBCA survey didn’t ask whether any of those SARs were of interest or useful to law enforcement. Anecdotally, the four U.S. mega banks indicate that law enforcement shows interest in (through requests for supporting documentation or grand jury subpoenas) in six percent to eight percent of the SARs they file.

I argue that the Alert/SAR and even Case/SAR ratios are all of interest, but tracking any of the inputs or process steps to SARs filed is like a car manufacturer tracking how many cars it builds, but not how many cars it sells, or how well those cars perform, how long they last, and how popular they are. The better measure for AML programs is “SARs purchased”, or SARs that provide value to law enforcement.

Also, there is much being written about how machine learning and artificial intelligence will transform anti-money laundering programs. Indeed, ML and AI proponents are convinced – and spend a lot of time trying to convince others – that they will disrupt and revolutionize the current “broken” AML regime. Among other targets within this broken regime is AML alert generation and disposition and reducing the false positive rate. The result, if we believe the ML/AI community, is a massive reduction in the number of AML analysts that are churning through the hundreds and thousands of alerts, looking for the very few that are “true positives” worthy of being labelled “suspicious” and reported to the government. But the fundamental problem that every one of those ML/AI systems has is that they are using the wrong data to train their algorithms and “teach” their machines: they are looking at the SARs that are filed, not the SARs that have tactical or strategic value to law enforcement.

Tactical or Strategic Value Suspicious Activity Reports – TSV SARs

The best measure of an effective and efficient financial crimes program is how well it is providing timely, effective intelligence to law enforcement. And the best measure of that is whether the SARs that are being filed are providing tactical or strategic value to law enforcement. How do you determine whether a SAR provides value to law enforcement? One way would be to ask law enforcement, and hope you get an answer. That could prove to be difficult. Can you somehow measure law enforcement interest in a SAR? Many banks do that by tracking grand jury subpoenas received to prior SAR suspects, law enforcement requests for supporting documentation, and other formal and informal requests for SARs and SAR-related information. As I write above, an Alert-to-SAR rate may not be a good measure of whether an alert is, in fact, “positive”. What may be relevant is an Alert-to-TSV SAR rate.

A TSV SAR is one that has either tactical value – it was used in a particular case – or strategic value – it contributed to understanding a typology or trend. And some SARs can have both tactical and strategic value. That value is determined by law enforcement indicating, within seven years of the filing of the SAR (more on that later), that the SAR provided tactical (it led to or supported a particular case) or strategic (it contributed to or confirmed a typology) value. That law enforcement response or feedback is provided to FinCEN through the same BSA Database interfaces that exist today – obviously, some coding and training will need to be done (for how FinCEN does it, see below). If the filing financial institution does not receive a TSV SAR response or feedback from law enforcement or FinCEN within seven years of filing a SAR, it can conclude that the SAR had no tactical or strategic value to law enforcement or FinCEN, and may factor that into decisions whether to change or maintain the underlying alerting methodology. Over time, the financial institution could eliminate those alerts that were not providing timely, actionable intelligence to law enforcement. And when FinCEN shares that information across the industry, others could also reduce their false positive rates.

FinCEN’s TSV SAR Feedback Loop

FinCEN is working to provide more feedback to the private sector producers of BSA reports. As FinCEN Director Ken Blanco recently stated:

“Earlier this year, FinCEN began the BSA Value Project, a study and analysis of the value of the BSA information we receive. We are working to provide comprehensive and quantitative understanding of the broad value of BSA reporting and other BSA information in order to make it more effective and its collection more efficient. We already know that BSA data plays a critical role in keeping our country strong, our financial system secure, and our families safe from harm — that is clear. But FinCEN is using the BSA Value Project to improve how we communicate the way BSA information is valued and used, and to develop metrics to track and measure the value of its use on an ongoing basis.”[14]

FinCEN receives every SAR. Indeed, FinCEN receives a number of different BSA-related reporting: SARs, CTRs, CMIRs, and Form 8300s. It’s a daunting amount of information. As FinCEN Director Ken Blanco noted in the same speech:

“FinCEN’s BSA database includes nearly 300 million records — 55,000 new documents are added each day. The reporting contributes critical information that is routinely analyzed, resulting in the identification of suspected criminal and terrorist activity and the initiation of investigations.

“FinCEN grants more than 12,000 agents, analysts, and investigative personnel from over 350 unique federal, state, and local agencies across the United States with direct access to this critical reporting by financial institutions. There are approximately 30,000 searches of the BSA data taking place each day. Further, there are more than 100 Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) review teams and financial crimes task forces across the country, which bring together prosecutors and investigators from different agencies to review BSA reports. Collectively, these teams reviewed approximately 60% of all SARs filed.

Each day, law enforcement, FinCEN, regulators, and others are querying this data: 7.4 million queries per year on average. Those queries identify an average of 18.2 million filings that are responsive or useful to ongoing investigations, examinations, victim identification, analysis and network development, sanctions development, and U.S. national security activities, among many, many other uses that protect our nation from harm, help deter crime, and save lives.”

This doesn’t tell us how many of those 55,000 daily reports are SARs, but we do know that in 2018 there were 2,171,173 SARs filed, or about 8,700 every (business) day. And it appears that FinCEN knows which law enforcement agencies access which SARs, and when. And we now know that there are “18.2 million filings that are responsive or useful to ongoing investigations, examinations, victim identification, analysis and network development, sanctions development, and U.S. national security activities” every year. But which filings?

The law enforcement agencies know which SARs provide tactical or strategic value, or both. So if law enforcement finds value in a SAR, it should acknowledge that, and provide that information back to FinCEN. FinCEN, in turn, could provide an annual report to every financial institution that filed, say, more than 250 SARs a year (that’s one every business day, and is more than three times the number filed by the average bank or credit union). That report would be a simple relational database indicating which SARs had either or both tactical or strategic value. SAR filers would then be able to use that information to actually train or tune their monitoring and surveillance systems, and even eliminate those alerting systems that weren’t providing any value to law enforcement.

Why give law enforcement seven years to respond? Criminal cases take years to develop. And sometimes a case may not even be opened for years, and a SAR filing may trigger an investigation. And sometimes a case is developed and the law enforcement agency searches the SAR database and finds SARs that were filed five, six, seven or more years earlier. Between record retention rules and practical value, seven years seems reasonable.

Law enforcement agencies have tremendous responsibilities and obligations, and their resources and budgets are stretched to the breaking point. Adding another obligation – to provide feedback to the banks, credit unions, and other private sector institutions that provide them with reports of suspicious activity – may not be feasible. But the upside of that feedback – that law enforcement may get fewer, but better, reports, and the private sector institutions can focus more on human trafficking, human smuggling, and terrorist financing and less on identifying and reporting activity that isn’t of interest to law enforcement – may far exceed the downside.

Final Word

As I wrote in the introduction, the Tactical or Strategic Value (TSV) SAR is not the only solution; indeed, we need more public/private sector partnerships, we need to move to cross-institutional and cross-jurisdictional collaborative investigations, we need more effective information sharing, and we need more efficient and effective monitoring/surveillance, alerting, investigations, and reporting. But the key to any reform is public sector feedback: I’m offering the TSV SAR as the vehicle for that feedback. I’m open to any better solutions, but perhaps we can start with the TSV SAR.

For more on alert-to-SAR rates, the TSV feedback loop, machine learning and artificial intelligence, see other articles I’ve written:

The TSV SAR Feedback Loop – June 4 2019

AML and Machine Learning – December 14 2018

Rules Based Monitoring – December 20 2018

FinCEN FY2020 Report – June 4 2019

FinCEN BSA Value Project – August 19 2019

BSA Regime – A Classic Fixer-Upper – October 29 2019

Jim Richards Walnut Creek, CA September 26, 2020

[1] 31 U.S. Code § 5311, declaration of purpose. From 1970 to 2001, the purpose of the records and reports was to provide a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings. The USA PATRIOT Act amended section 5311 by adding “or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism”.

[2] For a full analysis of FinCEN’s cost and burden estimate, see https://regtechconsulting.net/aml-regulations-and-enforcement-actions/fincens-estimate-of-the-costs-and-burden-of-filing-sars-is-evolving-but-needs-private-sector-input/

[3] Compare this information with the US Attorney’s Statistical Report, in the Appendix.

[4] In footnote 59 on page 25 the GAO set out its definition of human trafficking used for the survey: “we defined … human trafficking to include the movement of nonconsenting persons, often across borders, potentially through force, fraud, or coercion.”