In the last five years, FinCEN’s workload has gone up three times as much as its budget: if we care about preventing terrorist financing, human trafficking, and public corruption, Congress must fund our nation’s financial intelligence unit.

FinCEN is a bureau in the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Director of FinCEN reports to the Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence (TFI). In carrying out its mission, FinCEN has numerous statutory areas of responsibility:

- Developing and issuing regulations under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA);

- Enforcing compliance with the BSA in partnership with law enforcement and other regulatory partners;

- Serving as the U.S. Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) and maintaining a network of information sharing with FIUs in 164 partner countries;

- Receiving millions of new financial reports each year;

- Securing and maintaining a database of over 300 million reports;

- Analyzing and disseminating financial intelligence to federal, state, and local law enforcement, federal and state regulators, foreign FIUs, and industry; and

- Bringing together the disparate interests of law enforcement, FIUs, regulatory partners, and industry.

What is FinCEN’s mission? According to its most recent Congressional budget justification and annual performance plan and report (Fiscal Year 2021) submitted earlier this year (see https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/266/12.-FinCEN-FY-2021-CJ.pdf), FinCEN’s mission statement is “to safeguard the financial system from illicit use, combat money laundering, and promote national security through the strategic use of financial authorities and the collection, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence.”

FinCEN has a daunting and important mission – to safeguard the financial system – and Congress has placed upon FinCEN many critical responsibilities in safeguarding the financial system, everything from developing and enforcing the regulations for tens of thousands of private sector entities, receiving millions of reports (actually, more than 20 million) intended to provide a high degree of usefulness to government authorities, safeguarding those reports, and analyzing those reports and getting information back to over 6,700 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies (according to an FBI/DOJ notice published in the Federal Register on June 30, 2020).

With this daunting mission, and millions of reports to collect and analyze, tens of thousands of private sector entities to regulate, and thousands of law enforcement agencies to support, FinCEN must be a massive agency with an impressive budget.

Let’s take a look.

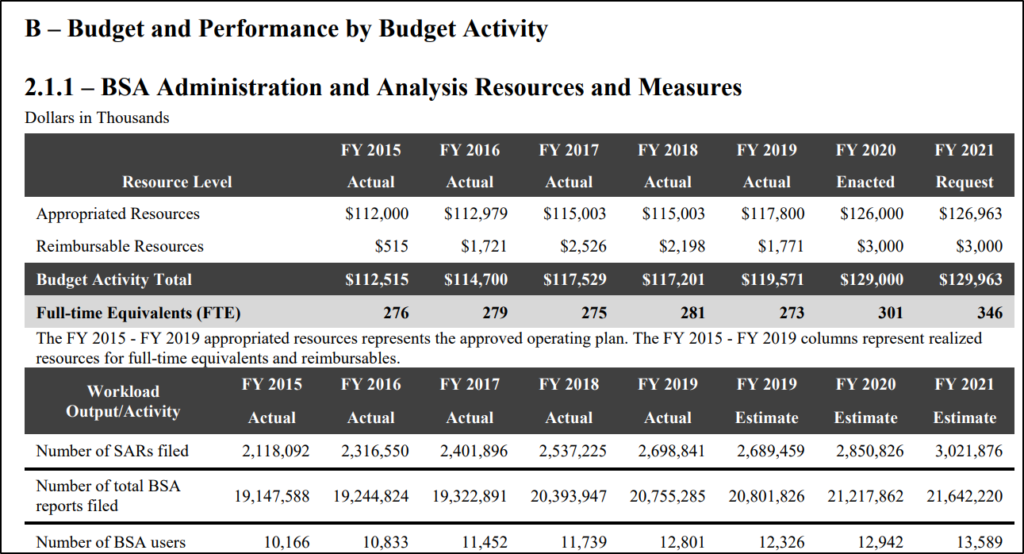

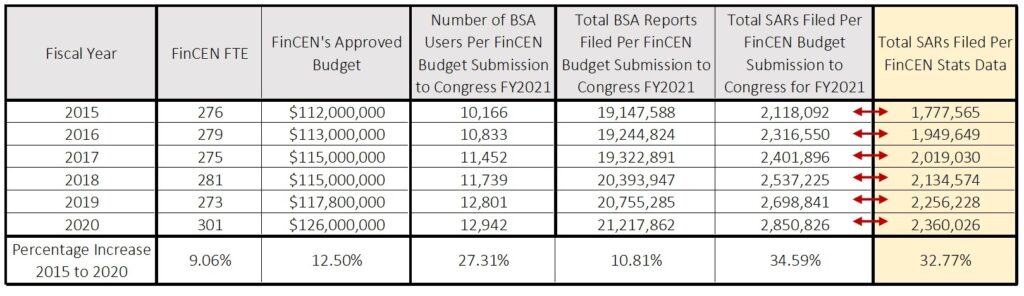

The first thing that should jump out at you, and will be a surprise to most people, is how small FinCEN is: less than 300 people and a budget that is eclipsed by many global banks’ financial crimes risk management departments. That aside, and clipped directly from the FY2021 budget request, this table shows FinCEN’s resource levels – people and budget – for six fiscal years and its requested resource levels for 2021. (FinCEN’s fiscal year – the federal government’s fiscal year – runs from October 1 to September 30). This table also shows FinCEN’s “workload output/activity”, or at least three measurable parts of its overall workload: (1) the total number of BSA reports filed each fiscal year, (2) the total number of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) each year (a subset of the total number of BSA reports), and (3) the number of people (generally law enforcement) who use, or access, FinCEN’s BSA database. What is not measured and shown here is the other work or output or activities FinCEN is responsible for (developing and enforcing BSA regulations and analyzing BSA reports and getting information back to law enforcement, for example).

A quick glance at this table suggests that the workload is going up: SARs have gone from just over 2 million in FY2015 to an estimated 3 million in FY2021; the total number of BSA reports continues to go up; and the number of BSA users has gone from 10,166 in FY2015 to an estimated 13,589 in FY2021.

Have FinCEN’s resources kept pace with its workload?

This is an important question. The recent “FinCEN Files” release by Buzzfeed News and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has caste a very negative spotlight on some large global banks as being the reason for, or the facilitators of, financial crime and corruption. Those stories have resulted in calls to reform what the media and others are calling a broken, ineffective, and inefficient regime. Although the journalists haven’t focused on FinCEN, it too has been receiving some unwarranted attention. Questions are being asked: banks and other financial institutions are reporting all this suspicious activity, so what is FinCEN doing about it?

FinCEN’s resources are not keeping pace with its workload.

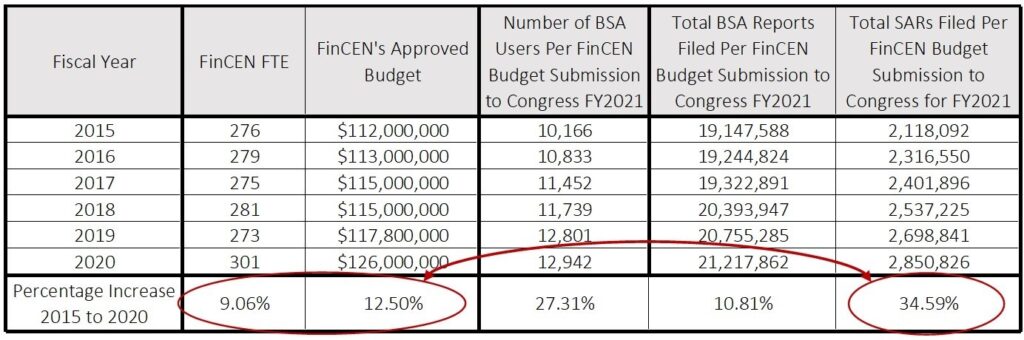

I reformatted FinCEN’s budget numbers in order to better compare the annual resource numbers with the workload numbers. Given the FinCEN Files focus on Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs), I’ve highlighted those:

What appears obvious from this is that the number of SARs has gone up about three times as fast as FinCEN’s resources: SARs are up almost 35% in five years, but FinCEN’s staffing has gone up just 9% and its overall budget has gone up just 12.5%. FinCEN’s resources aren’t keeping pace with its workload.

FinCEN has received more than 2 million SARs in each of the last six years … or has it?

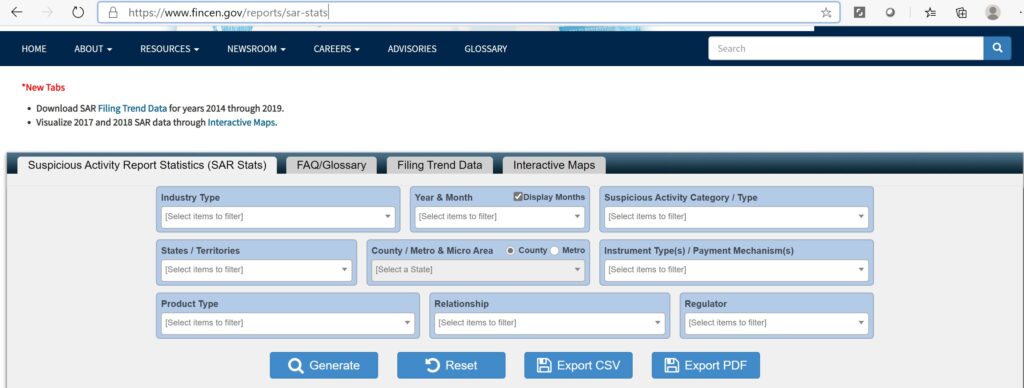

This is not a criticism of FinCEN. But when I saw those numbers in the budget request, I paused. FinCEN has a “SAR Stats” feature that allows the public to access FinCEN’s data on the number of SARs filed, by what type of filers, when, for what kind of suspicious activity, etc. It’s a great resource, and I use it a lot, and didn’t recall seeing more than 2 million SARs as far back as 2015. So I went back into the SAR Stats page …

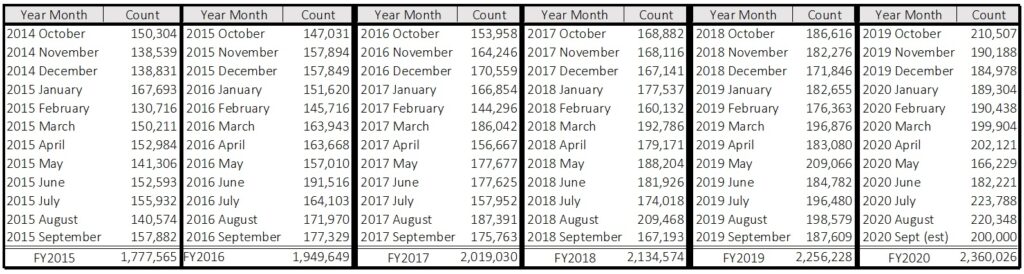

… and I exported the total number of SARs filed, by month, for the entire period of available data – January 2014 through August 2020. Here’s what FinCEN provided (reformatted):

These are the actual numbers exported from the FinCEN website (with the exception of September 2020, which isn’t yet available: I estimated the number of SARs filed for that one month). At first glance one can see that not all six fiscal years had more than 2 million filed SARs. So I put the two sets of data – the 2021 budget submission and the FinCEN SAR Stats – together for easier comparison:

These are the actual numbers exported from the FinCEN website (with the exception of September 2020, which isn’t yet available: I estimated the number of SARs filed for that one month). At first glance one can see that not all six fiscal years had more than 2 million filed SARs. So I put the two sets of data – the 2021 budget submission and the FinCEN SAR Stats – together for easier comparison:

I can’t explain the differences – there is likely a reason why the two sets of SAR data are different. But both show an increase in the number of SARs filed over the last five fiscal years that is triple the increase in FinCEN’s resources that are available to manage those SARs, analyze them, and disseminate actionable intelligence back to more than 6,000 law enforcement agencies in order to protect our financial system.

I can’t explain the differences – there is likely a reason why the two sets of SAR data are different. But both show an increase in the number of SARs filed over the last five fiscal years that is triple the increase in FinCEN’s resources that are available to manage those SARs, analyze them, and disseminate actionable intelligence back to more than 6,000 law enforcement agencies in order to protect our financial system.

Congress must support the fight against financial crime

If Congress is serious about fighting financial crime and protecting our financial system, it must provide FinCEN with the appropriate resources. So far it has failed to do so.