The following comments to FinCEN’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making (ANPRM) on AML Program Effectiveness were submitted by Jim Richards, founder and principal of RegTech Consulting LLC. The ANPRM was published in the Federal Register on September 17, 2020. It gave the public 60 days to submit comments. These comments were submitted on November 7, 2020.

Background on Jim Richards

Jim Richards is the principal and founder of RegTech Consulting LLC, a private consulting firm focused on providing strategic advice on all aspects of financial crimes risk management to AML software providers, financial technology start-ups, cannabis-related businesses, mid-size banks, and money services businesses. Mr. Richards is also a Senior Advisor to Verafin Inc., the leading provider of fraud detection and BSA/AML collaboration software for financial institutions in North America.

From 2005 through April 2018 Mr. Richards served as the BSA Officer and Director of Global Financial Crimes Risk Management for Wells Fargo & Co. As BSA officer, he was responsible for governance, training, and program oversight for BSA, anti-money laundering (AML), and sanctions for Wells Fargo’s global operations. As Director of Global Financial Crimes Risk Management, he was responsible for BSA, AML, counter-terrorist financing (CTF), external fraud, internal fraud and misconduct, the identity theft prevention program, global sanctions, financial crimes analytics, and high-risk customer due diligence.

Prior to his role with Wells Fargo, Mr. Richards was the AML operations executive at Bank of America. There, he was responsible for the operational aspects of Bank of America’s global AML and CTF monitoring, surveillance, investigations, and related SAR reporting. Mr. Richards represented Bank of America and Wells Fargo as a three-term member of the BSA Advisory Group (BSAAG). Mr. Richards was also a founding board member of ACAMS.

Prior to his 20-year career in banking, Mr. Richards was a prosecutor in Massachusetts, a barrister in Ontario, Canada, and a Special Constable with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He is the author of “Transnational Criminal Organizations, Cybercrime, and Money Laundering” (CRC Press 1998) Mr. Richards has a Bachelor of Commerce (BComm.) degree and Juris Doctorate (JD) from the University of British Columbia.

Introduction to the ANPRM

On September 17, 2020, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) published an Advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) in the Federal Register (85 FR 58023, Docket Number 2020-20527), seeking “public comment on potential regulatory amendments to establish that all covered financial institutions subject to an anti-money laundering program requirement must maintain an ‘effective and reasonably designed’ anti-money laundering program [that] assesses and manages risk as informed by a financial institution’s risk assessment, including consideration of anti-money laundering priorities to be issued by FinCEN consistent with the proposed amendments; provides for compliance with Bank Secrecy Act requirements; and provides for the reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.”

The BSAAG and AML Effectiveness Working Group Recommendations

The ANPRM noted that the BSAAG created an Anti-Money-Laundering Effectiveness Working Group (AMLE WG) in June 2019 to develop recommendations for strengthening the national AML regime by increasing its effectiveness and efficiency. Apparently the AMLE WG worked to “identify regulatory initiatives that would allow financial institutions to reallocate resources to better focus on national AML priorities set by government authorities, increase information sharing and public-private partnerships, and leverage new technologies and risk-management techniques – and thus increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the nation’s AML regime” and came up with five broad categories of recommendations. These were endorsed by the BSAAG plenary in October 2019 and evaluated by FinCEN, resulting in the September 16, 2020 ANPRM.

I commend FinCEN Director Blanco and his staff, the BSAAG members, and the members of the AML Working Group for their thoughtfulness, hard work, and courage in making these recommendations and publishing the ANPRM.

With the ANPRM, FinCEN is seeking public comments on whether an effective and reasonably designed AML program should have three components:

- It assesses and manages risk as informed by a financial institution’s risk assessment, including consideration of anti-money laundering priorities to be issued by FinCEN consistent with the proposed amendments;

- It provides for compliance with Bank Secrecy Act requirements; and

- It provides for the reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.”

As the ANPRM noted, the intent of the regulatory amendments under consideration is “to modernize the regulatory regime to address the evolving threats of illicit finance, and provide financial institutions with greater flexibility in the allocation of resources, resulting in the enhanced effectiveness and efficiency of anti-money laundering programs.”

The notice has three substantive sections. Section II sets the stage, with a historical look at the BSA/AML laws and regulations, from the first Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act of 1970 through the 2016 changes to the customer due diligence and beneficial ownership regulations. It then goes through the recent efforts of the BSA Advisory Group’s Effectiveness Working Group to modernize the AML regime, which culminated in five recommendations: developing and focusing on AML priorities, reallocating compliance resources, monitoring and reporting changes, enhancing information sharing, and advancing regulatory innovation. Those five recommendations were then taken up by FinCEN and incorporated into its proposed regulatory changes. Section III sets out those proposed changes, framed as the elements of an effective and reasonably designed AML program. The third substantive section, section IV, sets out the issues for comment: eleven questions to be answered.

A Startling Admission: There is no Regulatory Requirement for Financial Institutions to Have an Effective and Reasonably Designed AML Program

Perhaps the single most interesting part of the notice is in section III, where FinCEN writes “after consulting with the staffs of various supervisory agencies, and having considered the BSAAG recommendations and other BSA modernization efforts” FinCEN “is publishing this ANPRM seeking comment on whether it is appropriate to clearly define a requirement for an ‘effective and reasonably designed’ AML program in BSA regulations.” This last statement – whether it is appropriate to clearly define a requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program in BSA regulations – is, in fact, a startling admission. For years financial institutions have been fined billions of dollars, even charged criminally, for violating BSA regulations by failing to maintain and implement an AML program, and yet those regulations (apparently) do not clearly set out what is required for an effective and reasonably designed AML program.

The Crux of the ANPRM – Refocusing on the Singular Purpose of the BSA/AML Regime

Currently, the federal banking agencies (the Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC) that supervise and examine approximately 10,000 banks and credit unions for AML program requirements, only look at whether the financial institution “has designed, implemented, and maintains an adequate BSA/AML compliance program that complies with BSA regulatory requirements.”[1] Those agencies’ field examiners are not instructed to determine whether the institution is providing timely, effective information to government authorities.

It can be fairly argued that parts of the first two components of FinCEN’s proposed requirement for an effective and reasonably designed AML program are already in place and being considered by the regulatory agencies: whether the institution’s program assesses and manages financial crimes risk as informed by its risk assessment and whether it provides for compliance with BSA requirements. It can equally be argued – indeed, it is irrefutable – that the regulatory agencies are not currently considering whether the institution’s program provides for the reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.

This third regulatory focus – whether the program actually provides for the reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities – would be new. But this is not a new concept: indeed, the very purpose of the very first BSA/AML law, the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act of 1970, was to require financial institutions to keep records and file reports that “have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings”. This singular purpose, which I refer to as providing timely, effective information to government authorities, remains today: 31 USC section 5311 sets out the declaration of purpose:

It is the purpose of this subchapter (except section 5315) to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.

Over the years, notably with statutory and regulatory changes in 1986 and 1992 (discussed below), the singular purpose of the BSA/AML regime of providing timely, effective information to government authorities, has been overshadowed by, and then lost to, the programmatic compliance-focused regulatory requirements. This proposed change – of adding back the original purpose of the BSA – would bring the focus back, in part, on the very purpose of the BSA/AML regime: to provide timely, actionable information to government authorities.

FinCEN’s Request for Comments and Answers to Eleven Questions

In addition to seeking general comments concerning the potential rulemaking to incorporate a requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program into AML program regulations and to provide clarity on its application, FinCEN requested comments on eleven questions. I have set out those questions and provided comments (answers) where needed. Following those questions and comments/answers, I have provided a brief conclusion.

Question 1

Does this ANPRM make clear the concept that FinCEN is considering for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program through regulatory amendments to the AML program rules? If not, how should the concept be modified to provide greater clarity?

The stated purpose of the ANPRM is clear, but operational clarity for financial institutions will only come if it is clear that the regulatory agencies examine to the regulations, and not to the regulatory expectations set out in the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual (the Manual). FinCEN writes that it is “publishing this ANPRM seeking comment on whether it is appropriate to clearly define a requirement for an ‘effective and reasonably designed’ AML program in BSA regulations.” Later, FinCEN clarifies that it is considering regulatory amendments that would explicitly define an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program as one that has three elements:

- Identifies, assesses, and reasonably mitigates the risks resulting from illicit financial activity — including terrorist financing, money laundering, and other related financial crimes — consistent with both the institution’s risk profile and the risks communicated by relevant government authorities as national AML priorities;

- Assures and monitors compliance with the recordkeeping and reporting requirements of the BSA; and

- Provides information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities consistent with both the institution’s risk assessment and the risks communicated by relevant government authorities as national AML

The NPRM should make it clear that only the second element currently exists in both Titles 12 and 31 and their respective regulations, and that the first and third elements are new. For example, the purpose of 12 CFR § 21.21 “Procedures for monitoring Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) compliance” is described in 21.21(a):

“This subpart is issued to assure that all national banks and savings associations establish and maintain procedures reasonably designed to assure and monitor their compliance with the requirements of subchapter II of chapter 53 of title 31, United States Code, and the implementing regulations promulgated thereunder by the Department of the Treasury at 31 CFR Chapter X.”

And subsection 21.21(c) provides, in part, that the bank “shall develop and provide for the continued administration of a program reasonably designed to assure and monitor compliance” with subchapter II of chapter 53. So although the foundational purpose of the BSA regime – to have private sector financial institutions keep records and provide reports that have a “high degree of usefulness” to government authorities – there is nothing in the regulation(s) that speaks to that purpose. Rather, the purpose is to “assure and monitor compliance” with 31 CFR chapter X. What is the purpose of that regulation; or what does that regulation require?

The regulation, 31 CFR chapter X, provides the “how” to the “what” set out in the legislation, subchapter II of chapter 53 of title 31. Section 5311 is the declaration of purpose: “It is the purpose of this subchapter (except section 5315) to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.”

The program requirements are set out in section 5318(a) and (h):

5318. Compliance, exemptions, and summons authority

(a) General power of Secretary. – The Secretary of the Treasury may (except under section 5315 of this title and regulations prescribed under section 5315)

(2) require a class of domestic financial institutions or nonfinancial trades or businesses to maintain appropriate procedures to ensure compliance with this subchapter and regulations prescribed under this subchapter or to guard against money laundering;

*****

(h) Anti-money laundering programs.

(1) In general. – In order to guard against money laundering through financial institutions, each financial institution shall establish anti-money laundering programs, including, at a minimum

(A) the development of internal policies, procedures, and controls;

(B) the designation of a compliance officer;

(C) an ongoing employee training program; and

(D) an independent audit function to test programs.

(2) Regulations – The Secretary of the Treasury, after consultation with the appropriate Federal functional regulator (as defined in section 509 of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act), may prescribe minimum standards for programs established under paragraph (1) …

So the law provides what Congress intended when it comes to the Bank Secrecy Act: the overall purpose is to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities, and that purpose is met, in part, by requiring financial institutions to maintain appropriate procedures and establish AML programs to guard against money laundering. The law also provides that minimum standards for these programs are to be prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury through regulations.

Those regulations are set out at 31 CFR chapter X. Chapter X includes general provisions required of all financial institutions (in section 1010) and then specific provisions for the eleven categories of financial institutions subject to the regulations (in sections 1020-1030) such as banks (1020), casinos (1021), MSBs (1022), etc. None of those sections includes a “purpose” statement, and none of them compel financial institutions to provide reports that have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities. None of them include the phrase “high degree of usefulness”.

Perhaps most important, though, none of the five full editions of the FFIEC BSA/AML Exam Manual, nor the 2016 and 2020 partial amendments, compel examiners to examine financial institutions on whether they provide reports that have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities or even include the phrase “high degree of usefulness”. Put another way, when conducting BSA examinations, neither FinCEN nor any of the financial regulatory agencies consider whether the institution is complying with the very purpose of the BSA.

To put this in perspective, the purpose of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is to encourage financial institutions to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they do business, including low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods. When conducting examinations of financial institutions’ CRA compliance, regulators will, in fact, look to whether those institutions are meeting the credit needs of the communities in which they do business, including low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods. Not so with the BSA: the purpose of the BSA is to require financial institutions to submit certain reports and keep certain records where they have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities, yet those institutions are not examined on whether the reports they submit or the records they keep have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.

Question 2

Are this ANPRM’s three proposed core elements and objectives of an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program appropriate? Should FinCEN make any changes to the three proposed elements of an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program in a future notice of proposed rulemaking?

As described above, FinCEN is considering regulatory amendments that would define an “effective and reasonably designed” program as one that:

- Identifies, assesses, and reasonably mitigates the risks resulting from illicit financial activity, including terrorist financing, money laundering, and other related financial crimes, consistent with both the institution’s risk profile and the risks communicated by relevant government authorities as national AML priorities;

- Assures and monitors compliance with the recordkeeping and reporting requirements of the BSA; and

- Provides information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities consistent with both the institution’s risk assessment and the risks communicated by relevant government authorities as national AML

The order of the three elements is important, as it suggests a priority. I suggest a reordering, or re-prioritization of the elements. I would begin with the very purpose of the BSA, which is for financial institutions to keep records, and submit reports, that provide a high degree of usefulness to law enforcement.

Also, only two of the three components have a “consistent with” provision. All three components should be risk-based. Also, the two components’ “consistent with” provisions are slightly different. The “identified, assesses, and reasonably mitigates the risks” component is to be consistent with an institution’s risk profile, while the “provides information” component is to be consistent with an institution’s risk assessment. A risk profile is based, in large part, on the assessment of the risks: both (all three) components should be the same, and the consistency should be against the institution’s risk profile rather than its risk assessment. The result would be this:

An “effective and reasonably designed” program as one that:

- Provides information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities;

- Identifies, assesses, and reasonably mitigates the risks resulting from illicit financial activity, including terrorist financing, money laundering, and other related financial crimes; and

- Assures and monitors compliance with the recordkeeping and reporting requirements of the BSA

consistent with both the institution’s risk profile and the risks communicated by relevant government authorities as national AML priorities.

As I wrote above, over the years, notably with statutory and regulatory changes in 1986 and 1992, the singular purpose of the BSA/AML regime of providing timely, effective information to government authorities, has been overshadowed by, and then lost to, the programmatic compliance-focused regulatory requirements. Those changes are worth describing.

The first change came about from the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986 (MLCA), PL 99–570, 100 Stat. 3207 (Oct. 27, 1986) was enacted to essentially solve two problems: customers of banks were avoiding the recordkeeping and reporting requirements by “structuring” their transactions, and financial institutions were ignoring their responsibilities to keep those records and file reports. The MLCA made structuring and money laundering crimes, and it required the federal regulatory agencies (1) to issue regulations for covered financial institutions to “establish and maintain procedures reasonably designed to assure and monitor the compliance” of such institutions with the reporting and some recordkeeping requirements of the BSA; and (2) to issue enforcement actions when those institutions fail to do so.

In its ANPRM, FinCEN writes that the MLCA “amended the BSA, underscoring the importance of reporting information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.” In fact, it did not. There is no mention of the importance of reporting information with a high degree of usefulness in the MLCA. And the effect of the new “procedures” regulations – and examination of and enforcement of those new regulations – was to begin the shift away from focusing on providing useful information to meeting regulatory, procedural regulations. The MLCA gave birth to two new industries: the professional money launderer, and the professional AML compliance officer.

The second change came about with the Annunzio-Wylie Anti-Money Laundering Act of 1992 (Annunzio-Wylie), Title XV of PL 102–550, 106 Stat. 3672 (Oct. 28, 1992). Annunzio-Wylie gave the industry the “four pillar program” requirements we are so familiar with today by authorizing Treasury to issue regulations requiring all financial institutions to maintain ‘‘minimum standards’’ of an AML program. The minimum standards, for both FinCEN and the banking agencies, require financial institutions to establish and maintain procedures “reasonably designed” to assure and monitor compliance with the requirements of the BSA and include (1) system of internal controls, (2) a BSA compliance officer, (2) independent testing, and (4) training. Like the MLCA, Annunzio-Wylie did not include references to providing information with a high degree of usefulness to law enforcement.

Title III of the Patriot Act (the International Counter Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act, part of the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001, PL 107-56, 115 Stat. 272 (Oct. 26, 2001) did remind the industry of the importance of providing information with a high degree of usefulness to government agencies. Since 1970, the purpose of the BSA (set out in 31 USC s. 5311) had been to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings. With the horrific events of 9/11, that purpose was expanded: to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.

But that expanded purpose did not make it into the regulations – either the banking agencies’ regulations in Title 12 or FinCEN’s regulations in Title 31. And notwithstanding that expanded purpose, the Patriot Act added more program requirements, notably the customer identification program (CIP) requirements. Regulations followed roughly two years after the Patriot Act was signed into law; and in April 2005 the first of five FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manuals was published. You will not find any instructions to regulatory agencies’ examiners in any of the Manuals that tells them to evaluate whether the financial institution is providing information with a high degree of usefulness to law enforcement. In fact, the phrase “high degree of usefulness” does not appear in the Manual, other than in Appendix D which is a list of the twenty-six types of financial institutions that are covered by the BSA and a twenty-seventh type that could be covered: “Any other business designated by the Secretary whose cash transactions have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory matters.” The irony, of course, is that if this other business is required to have a BSA program, and to keep records and provide reports on its cash transactions because they would have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory matters, it would not be examined on whether it did, in fact, provide reports of information with a high degree of usefulness. (and note to FinCEN: 31 USC 5312(a)(2)(Z) needs to be amended to add “, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.”).

Question 3

Are the changes to the AML regulations under consideration in this ANPRM an appropriate mechanism to achieve the objective of increasing the effectiveness of AML programs? If not, what different or additional mechanisms should FinCEN consider?

These proposed changes are an appropriate mechanism, primarily because they would shift the non-binding regulatory expectations from guidance documents and the BSA/AML Examination Manual, which do not have the force of law, to regulations, which do have the force of law and are enforceable. But more can and should be done.

Question 4

Should regulatory amendments to incorporate the requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program be proposed for all financial institutions currently subject to AML program rules? Are there any industry-specific issues that FinCEN should consider in a future notice of proposed rulemaking to further define an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program?

FinCEN notes that, as regulations for different segments of the financial industry have been promulgated at different times in the past, such AML program regulations have evolved and, consequently, contain provisions that differ among the various industries subject to AML program requirements. For example, the AML program requirement for money services businesses (31 CFR 1022.210(a)) already contains an effectiveness component.[2] FinCEN invites comments from all covered industries subject to AML program regulations as to how a requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program would impact their industry. Furthermore, FinCEN invites comment as to whether any industry-specific modifications would be appropriate to consider in future rulemaking.

Question 5

Would it be appropriate to impose an explicit requirement for a risk-assessment process that identifies, assesses, and reasonably mitigates risks in order to achieve an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program? If not, why? Are there other alternatives that FinCEN should consider? Are there factors unique to how certain institutions or industries develop and apply a risk assessment that FinCEN should consider? Should there be carve-outs or waivers to this requirement, and if so, what factors should FinCEN evaluate to determine the application thereof?

Yes, it would be appropriate to impose a regulatory requirement that an effective and reasonably designed AML program is risk-based, and a formal risk assessment process determines the risks (and corresponding controls and whether those controls are addressing and mitigating those risks).

As the regulatory agencies noted in their September 11, 2018 Interagency Statement Clarifying the Role of Supervisory Guidance, “[u]nlike a law or regulation, supervisory guidance does not have the force and effect of law, and the agencies do not take enforcement actions based on supervisory guidance. Rather, supervisory guidance outlines the agencies’ supervisory expectations or priorities and articulates the agencies’ general views regarding appropriate practices for a given subject area.”[3]

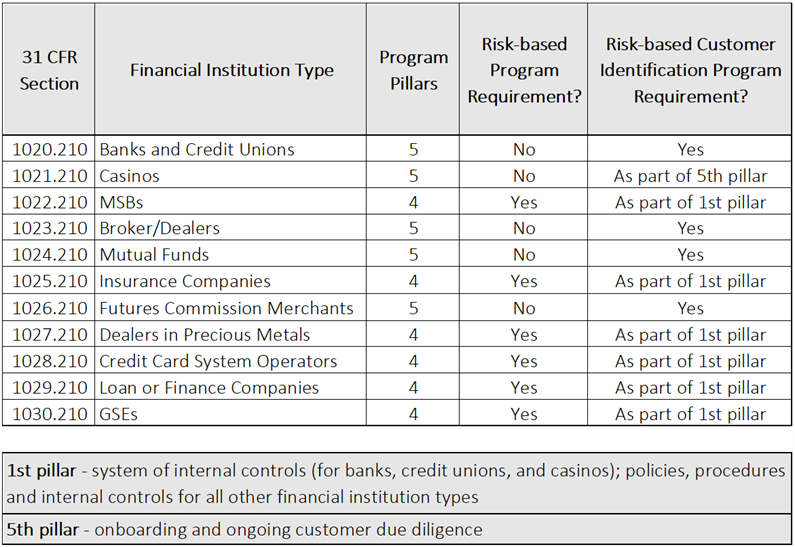

As set out above, 31 CFR Part X includes specific requirements for eleven classes of financial institutions. As summarized in the table below, six of the eleven classes already have requirements for risk-based AML programs, while all eleven have either explicit and risk-based Customer Identification Program (CIP) requirements or embed risk-based customer identification requirements in the internal control pillar of the AML program requirement.

A reasonably simple solution is to adopt and, where necessary, adapt the current risk-based program requirements to those financial institution types that currently do not have them.

Question 6

Should FinCEN issue Strategic AML Priorities, and should it do so every two years or at a different interval? Is an explicit requirement that risk assessments consider the Strategic AML Priorities appropriate? If not, why? Are there alternatives that FinCEN should consider?

The only reason a risk assessment would consider strategic AML priorities is for the institution to then adapt its program and underlying controls to those priorities. Programmatic and control changes can take years to design, test, and implement, and perfect. Requiring programs and controls to adapt to bi-annual changes to FinCEN’s strategic AML priorities will never allow an institution to actually implement a program. Any “strategic” priorities have to be priorities over a five year or longer time period; otherwise they are tactical.

And what are these national or strategic priorities? The most recent were set out in Treasury’s 2020 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing (February 6, 2020). That national strategy described ten vulnerabilities: lack of beneficial ownership requirements at the time of company formation, lack of BSA regulations impacting real estate professionals and key gatekeepers such as attorneys and accountants, correspondent banking, cash, complicit professionals, compliance weaknesses at regulated financial institutions, digital assets, MSBs, securities broker/dealers, and casinos. The national strategy listed three key priorities: (1) increase transparency and close legal framework gaps for beneficial ownership, real estate, and digital assets; (2) continue to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the regulatory framework; and (3) enhance the current AML/CFT operational framework.

Question 7

Aside from policies and procedures related to the risk-assessment process, what additional changes to AML program policies, procedures, or processes would financial institutions need to implement if FinCEN implemented regulatory changes to incorporate the requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program, as described in this ANPRM? Overall, how long of a period should FinCEN provide for implementing such changes?

Any regulatory change requires a financial institution to assess the change, determine the policy, systems/technology, and personnel changes that would need to be made, and determine the costs of and time needed to implement those changes across all of the businesses, delivery channels, and customer groups of the institution. For the very small percentage of financial institutions that have international operations, the non-US jurisdictional regulatory impacts must also be determined, and any changes made.

As FinCEN did with the beneficial ownership rule, I would provide a two-year implementation period.

Question 8

As financial institutions vary widely in business models and risk profiles, even within the same category of financial institution, should FinCEN consider any regulatory changes to appropriately reflect such differences in risk profile? For example, should regulatory amendments to incorporate the requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program be proposed for all financial institutions within each industry type, or should this requirement differ based on the size or operational complexity of these financial institutions, or some other factors? Should smaller, less complex financial institutions, or institutions that already maintain effective BSA compliance programs with risk assessments that sufficiently manage and mitigate the risks identified as Strategic AML Priorities, have the ability to “opt in” to making changes to AML programs as described in this ANPRM?

No comments.

Question 9

Are there ways to articulate objective criteria and/or a rubric for examination of how financial institutions would conduct their risk-assessment processes and report in accordance with those assessments, based on the regulatory proposals under consideration in this ANPRM?

In the narrative to this question, FinCEN wrote:

“FinCEN appreciates that, in order for the regulatory proposals as described in this ANPRM to achieve the objective of increased effectiveness of the overall U.S. AML regime, the supervisory process must support and reinforce this objective. Indeed, FinCEN has consulted with the staffs of various Federal supervisory agencies in developing this ANPRM, and FinCEN requests comments on how the supervisory regime could best support the objectives as identified in this ANPRM.”

So we know that FinCEN has consulted with the staffs of various Federal supervisory agencies, but we don’t know the nature of, or results from, those consultations. This question can only be answered by those supervisory agencies: are they going to support and reinforce the objective of increased effectiveness of the overall US AML regime, or keep the status quo?

Question 10

Are there ways to articulate objective criteria and/or a rubric for independent testing of how financial institutions would conduct their risk-assessment processes and report in accordance with those assessments, based on the regulatory proposals under consideration in this ANPRM?

I would defer to auditors on how they can set out objective criteria or a statement of purpose (rubric) on how they would independently test a more formalized, regulatory-driven risk assessment process.

Question 11

A core objective of the incorporation of a requirement for an “effective and reasonably designed” AML program would be to provide financial institutions with greater flexibility to reallocate resources towards Strategic AML Priorities, as appropriate. FinCEN seeks comment on whether such regulatory changes would increase or decrease the regulatory burden on financial institutions. How can FinCEN, through future rulemaking or any other mechanisms, best ensure a clear and shared understanding in the financial industry that AML resources should not merely be reduced as a result of such regulatory amendments, but rather should, as appropriate, be reallocated to higher priority areas?

I first became a BSA Officer at a large bank in the late 1990s, and continued as a BSA Officer until April 2018 at successively large financial institutions. The regulatory burden increased with each year, with each legislative change (there have been only two substantive regulatory changes in the last twenty years – in 2001 and 2004), each regulatory change, with every change in regulatory expectation and guidance (e.g., the five full editions of the BSA Exam Manuals from 2005 through 2014, and the partial changes to the Exam Manual in 2016 and 2020), and with heightened expectations from the increasing number and severity of regulatory sanctions and enforcement actions. The regulatory burden has never decreased. In fact, the single biggest risk a BSA Officer must manage today is regulator risk – managing the management of risk management so as not to incur MRAs, MRIAs, non-public Part 30 orders, or public enforcement actions.

The BSAAG AML Working Group’s first recommendation addresses this issue of how to ensure that resources are effectively allocated. The title of that first recommendation was “Developing and Focusing on AML Priorities”, and the Working Group “recommended that stakeholders refocus the national AML regime to place greater emphasis on providing information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities based on national AML priorities, in order to promote effective outputs over auditable processes and to ensure clearer standards for measuring effectiveness in evaluating AML programs.”

But there is one critical aspect of this that does not appear to have been assessed, let alone resolved: in order for regulated financial institutions to be examined on how well they are providing information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities, those government authorities will need to provide feedback on what information does, in fact, have a high degree of usefulness. Currently, there is no systemic way for law enforcement to provide feedback to institutions on whether a particular SAR or CTR (the two primary BSA reports), or any SAR or CTR, or any type of typology of SAR or CTR, provides information with a high degree of usefulness, and what type of use – tactical or strategic – that information has.

I have offered solutions on how law enforcement can (and should) provide feedback, principally through what I have described as “Tactical or Strategic Value” Suspicious Activity Reports, or TSV SARs. See https://regtechconsulting.net/uncategorized/fincen-files-reforming-aml-regimes-through-tsv-sars-tactical-or-strategic-value-suspicious-activity-reports/

The Working Group’s second recommendation dealt with BSA compliance resource reallocation, and recommended reducing or eliminating activities that are not required by law or regulation, make limited contributions to meeting risk-management objectives, and supply less useful information to government authorities. The Working Group concluded that resources freed from these activities could be reallocated to address areas of risk and national AML priorities. The Working Group specifically suggested that the application of existing model-risk-management guidance to AML systems be revised.

Revising existing model-risk-management guidance to AML systems assumes there is existing model-risk-management guidance to AML systems. But there isn’t any such guidance. The model risk management guidance – from 2000 and revised in 2011 – was never intended to be applied against AML systems. None of the five editions of the FFIEC Exam Manual, the four after the original 2000 guidance and the one following the 2011 revision of the guidance, make any reference to the model risk management guidance. If AML systems are to be subject to strict model governance, then that governance must be set out in binding regulation subject to public review and comment. And AML systems should not be subject to the same strict model governance requirements as Value-At-Risk models, liquidity models, or even consumer lending models. Nothing has more adversely impacted the ability of large financial institutions to fight financial crime, human trafficking, kleptocracy, nuclear proliferation, etc., as the strict, pedantic, dogmatic application of model risk governance.

Conclusion

I commend FinCEN, the members of the BSAA Advisory Group – particularly those members that served on the AML Working Group – for the hard work, collaboration, and courage it took to make and accept the recommendations and publish the Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making.

Everyone in the public- and private-sector AML/CFT communities wants to (in the words of the AML Working Group) “identify regulatory initiatives that would allow financial institutions to reallocate resources to better focus on national AML priorities set by government authorities, increase information sharing and public-private partnerships, and leverage new technologies and risk-management techniques – and thus increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the nation’s AML regime.” As the BSA Exam Manual instructs us (at page 7):

“The BSA is intended to safeguard the U.S. financial system and the financial institutions that make up that system from the abuses of financial crime, including money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit financial transactions. Money laundering and terrorist financing are financial crimes with potentially devastating social and financial effects. From the profits of the narcotics trafficker to the assets looted from government coffers by dishonest foreign officials, criminal proceeds have the power to corrupt and ultimately destabilize communities or entire economies. Terrorist networks are able to facilitate their activities if they have financial means and access to the financial system. In both money laundering and terrorist financing, criminals can exploit loopholes and other weaknesses in the legitimate financial system to launder criminal proceeds, finance terrorism, or conduct other illegal activities, and, ultimately, hide the actual purpose of their activity.”

The Exam Manual then continues with this:

“Banking organizations must develop, implement, and maintain effective AML programs that address the ever-changing strategies of money launderers and terrorists who attempt to gain access to the U.S. financial system. A sound BSA/AML compliance program is critical in deterring and preventing these types of activities at, or through, banks and other financial institutions.”

This is where I differ, and where I have directed most of my comments. Although a sound BSA/AML compliance program is important in deterring and preventing financial crime at or through banks and other financial institutions, the primary function of a program is providing timely, actionable information to law enforcement. I suggest the following:

“Banking organizations must provide government authorities with timely and effective reports of information that have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism, and in order to be able to do so must develop, implement, and maintain effective AML programs that address the ever-changing strategies of money launderers and terrorists who attempt to gain access to the U.S. financial system. Providing timely, effective information that has a high degree of usefulness to government authorities is critical in deterring and preventing these types of activities at, or through, banks and other financial institutions.”

It is this shift from a inputs- or process-centric regime to an outputs- or results-centric regime that is reflected in the third leg (which I would make the first leg) of FinCEN’s proposed “effective and reasonably designed” AML program requirements.

Requiring financial institutions to provide timely, effective information that has a high degree of usefulness to government authorities is the singular purpose of the BSA.[4] If financial institutions are to be examined for their compliance with the BSA, and held accountable for failing to comply with the BSA, they must be examined on whether they are, in fact, providing timely, effective information that has a high degree of usefulness to government authorities. Today, they are not. Hopefully, in the near future, through the rule-making process that FinCEN has initiated, they will be. The result will be a more efficient and effective US AML regime that is better able to protect and defend individuals, communities, institutions, the financial system, and our homeland.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment.

Jim Richards

November 7, 2020

Endnotes

[1] April 15, 2020 revision to the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual, page 18. This is a change from the 2014 Manual, which instructed examiners to “determine whether the bank has developed, administered, and maintained an effective program for compliance with the BSA and all of its implementing regulations.” Whether the standard is “adequate” or “effective”, examiners are not asked to determine whether the institution is providing timely, effective information to government authorities.

[2] Specifically, it provides that each money services business, as defined by §1010.100(ff), shall develop, implement, and maintain an effective anti-money laundering program. An effective anti-money laundering program is one that is reasonably designed to prevent the money services business from being used to facilitate money laundering and the financing of terrorist activities.

[3] On November 5, 2020 those same agencies published a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (85 FR 70512) seeking to codify the September 11, 2018 Interagency Statement.

[4] In fact, the proposed AML Act of 2020, an amendment to the proposed National Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2021, would amend 31 USC s. 5311 to add four additional “purposes” to the BSA to the current purpose of providing information that is highly useful to government agencies. The first of the four new purposes would be “to prevent the laundering of money and financing of terrorism through the establishment by financial institutions of reasonably designed risk-based programs.” The AML Act (section 5101) would also amend 31 USC s. 5318(h), the AML program requirement to reflect these changes in purpose.