Executive Summary of the AML Act of 2020

On December 3, 2020 the Senate and House jointly issued a Conference Report on the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 (the “NDAA”). The Conference Report is 4,517 pages long.[1] The NDAA contains eight divisions – Division F is the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (the “AML Act of 2020”). The House passed the NDAA on December 8th with a vote of 335-78 (out of 435 Members): the Senate passed the NDAA on December 11th with a vote of 84-13 (out of 100 Senators). The NDAA will be headed to the President’s desk, where he can sign it into law or veto it. If vetoed, both chambers have veto-proof majorities (two-thirds) and can over-ride the veto, if they choose to exercise those powers.

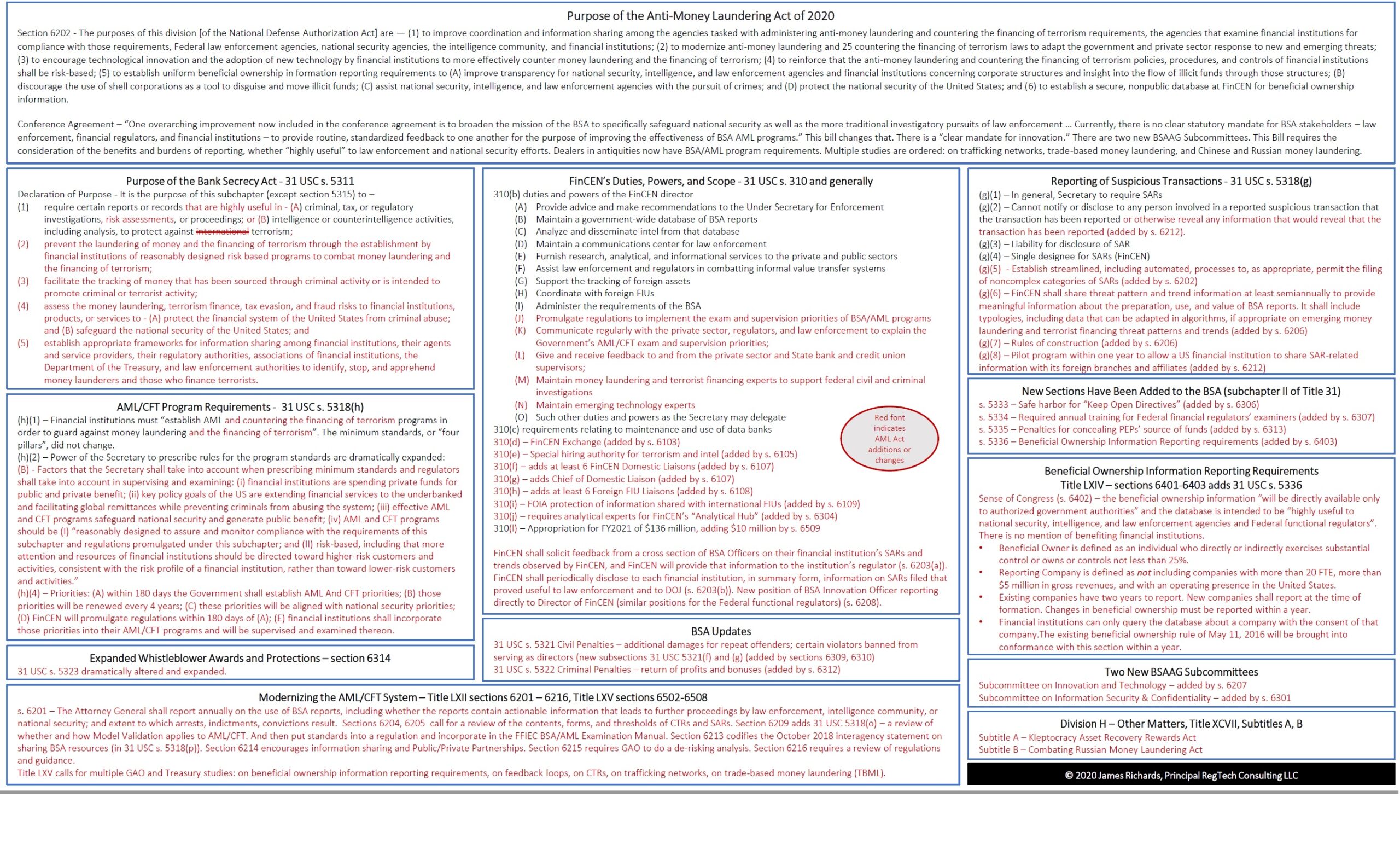

If signed by the President, or Congress over-rides a Presidential veto, the AML Act of 2020 will usher in the most profound changes to the U.S. anti-money laundering regime since the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001.[2] As described in more detail below, the AML Act of 2020 broadens the mission or purpose of the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) to include national security; formalizes the risk-based approach for financial institutions’ compliance programs; greatly expands the duties, powers, and functions of FinCEN; aligns the regulatory agencies’ supervision and examination priorities with the expanded purposes of the BSA; increases civil and criminal penalties for violations of the BSA; calls for multiple studies and reports; and establishes a beneficial ownership information reporting regime. The result is that the US is moving from a US-focused, regulator-versus-regulated, compliance-focused regime to a global, public/private partnership focused on fighting all financial crimes.

Of note is what is not in the AML Act that should be there. What is not in the AML Act are any references to, or changes to, the laws that give duties and powers to the Federal functional regulators. What we call the Bank Secrecy Act is actually three different laws, or parts of the US Code: 12 USC s. 1829b (“retention of records by insured depository institutions”), 12 USC Part 21 (“financial recordkeeping”, sections 1951-1959), and 31 USC subchapter II (“ records and reports on monetary instruments and transactions”, sections 5311-5314, 5316-5322). As explained in the following section, title 12 is “Banks & Banking” and includes the laws relating to the Federal functional regulators, and title 31 is “Money & Finance” and includes the laws relating to Treasury and FinCEN. The AML Act changes the title 31 laws (and regulations) but not the title 12 laws (and regulations) that collectively make up the BSA.[3] It remains to be seen how the title 12 regulators will be impacted, and how willing they will be to being impacted, by the title 31 changes.

Finally, whatever the impacts of the AML Act will be may not be fully realized for years. For example, the USA PATRIOT Act, which included Title III, the International Counter-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act of 2001, was passed in October 2001; regulations implementing the Act were issued in 2002 and 2003; and regulatory guidance, in the form of the first FFIEC BSA/AML Exam Manual, wasn’t published until April 2005 (and that Manual was revised in 2006, 2007, 2010, and 2014 to reflect changing regulatory guidance). We can expect something similar with the AML Act of 2020: it calls for multiple studies and reports to Congress over the next two years; regulations will need to be issued over the next year to three years; the Exam Manual will need to be revised; regulators will need to be trained; and regulatory guidance will evolve.

I was pleased to see that many of the things I’ve been calling for over the years have been included in the AML Act. Most notably are the provisions relating to – even requiring – the public sector consumers of BSA reports to provide feedback to the private sector producers of BSA reports. My most recent article on what I’ve called “TSV SARs” or Tactical or Strategic Value SARs, is from October 1, 2020: Reforming the AML Regime Through TSV SARs

Background on the US Code, Code of Federal Regulations, and Regulatory Guidance

For those not familiar with how US laws and regulations work, a short primer is in order.

The Conference Report and AML Act of 2020 contain references to the United States Code (“USC”), the Code of Federal Regulations (“CFR”), and regulatory guidance such as the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual.

Legislation, or laws, are set out in the United States Code, the codification by subject matter of the general and permanent laws of the United States. The U.S. Code is divided by broad subjects into 53 titles and published by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives.[4] The first six titles set out the laws relating to the functioning of the government generally. Titles 7 through 50 are alphabetical: title 7 is Agriculture, title 50 is War & National Defense. The main titles relating to anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) are:

- Title 12 Banks & Banking – laws relating to the Federal financial regulatory agencies such as the Federal Reserve, FDIC, OCC

- Title 18 Crimes & Criminal Procedure – criminal laws such as structuring and operating an unlicensed money transmitter

- Title 26 – Internal Revenue Code – tax-related crimes and some BSA-related forms such as the Form 8300 (reporting cash received by a trade or business)

- Title 31 Money & Finance – the Bank Secrecy Act is part of title 31: subchapter II, sections 5311 – 5322. The AML Act of 2020 adds sections 5333-5336 to subchapter II

- Title 50 War & National Defense – U.S. sanctions laws administered by OFAC are in this title.[5]

Laws are described by the title and the section: 31 USC s. 5311, for example, is the “purpose” section of the laws known as the BSA that are codified in title 31.

Where laws generally describe “what” Congress has enacted, how those laws are implemented and enforced are set out in regulations issued by the appropriate executive branch agency or department, such as the Treasury Department and the Federal financial regulators. Regulations are set out in the Code of Federal Regulations. The OCC’s regulations are set out in Part 21 of title 12 of the Code ofFederal Regulations – 12 CFR Part 21 – while FinCEN’s regulations are set out in Part X of title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations – 31 CFR Part X.[6]

Regulations provide the “how” and follow the “what of the law: an example of laws and corresponding regulations is 31 USC s. 5318(h), the law that requires all financial institutions to have AML/CFT programs, and its implementing regulation at 31 CFR s. 1020.200, the general program requirements for banks.

All of the Federal functional regulators and FinCEN issue what is called “supervisory guidance” to set out their expectations or priorities. For AML and CFT purposes, this supervisory guidance has been collected and compiled by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, or FFIEC, into an examination manual that includes their collective guidance to their examiners on AML and CFT laws, regulations, and expectations. It is available at https://bsaaml.ffiec.gov. Although this guidance does not create enforceable requirements – those requirements are in the laws and regulations – the guidance does shape how financial institutions design, build, maintain, and update their programs, and how auditors and examiners test and examine those programs.

Explanation of this Summary of the AML Act of 2020

As set out above, the Conference Report for the NDAA is over 4,500 pages long. The AML Act of 2020, Division F of the NDAA, is at pages 2,843 – 3,078 (it is 235 pages long). The AML Act of 2020 is made up of 56 sections in five titles.[7] Sections 6001-6003 set out the title of the act, its purposes, and definitions of key terms. Following those three introductory sections are the five titles:

- Title LXI – Strengthening Treasury Financial Intelligence, Anti-Money Laundering, and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Programs (sections 6101-6112)

- Title LXII – Modernizing the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism System (sections 6201-6216)

- Title LXIII – Improving Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Communication, Oversight, and Processes (sections 6301-6314)

- Title LXIV – Establishing Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements (sections 6401-6403)

- Title LXV – Miscellaneous (sections 6501-6511)

Scattered throughout many of the titles and sections are changes to particular aspects of, or themes of, the current AML/CFT regime. This summary, therefore, is arranged by those aspects or themes rather than going through the fifty-six sections and five titles in order. Text appearing in red font indicates a change or addition to language in laws or regulations: the intent is for the reader to see what has been added (or, in one case, taken away) from existing laws or regulations.

This is by no means a complete review, assessment, analysis, and commentary on the AML Act of 2020. However, I trust it is a good primer for those interested in contributing to the discussion around, and efforts to promote, a more effective, efficient, courageous, compassionate, and inclusive public and private sector effort at mitigating and, to the extent possible, eliminating money laundering ,terrorist financing, and other financial crimes.

Purposes of the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020

Section 6202 of the AML Act describes the purposes of the Act. The full text of this section is set out below:

- to improve coordination and information sharing among the agencies tasked with administering anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism requirements, the agencies that examine financial institutions for compliance with those requirements, Federal law enforcement agencies, national security agencies, the intelligence community, and financial institutions;

- to modernize anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism laws to adapt the government and private sector response to new and emerging threats;

- to encourage technological innovation and the adoption of new technology by financial institutions to more effectively counter money laundering and the financing of terrorism;

- to reinforce that the anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism policies, procedures, and controls of financial institutions shall be risk-based;

- to establish uniform beneficial ownership in formation reporting requirements to (A) improve transparency for national security, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies and financial institutions concerning corporate structures and insight into the flow of illicit funds through those structures; (B) discourage the use of shell corporations as a tool to disguise and move illicit funds; (C) assist national security, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies with the pursuit of crimes; and (D) protect the national security of the United States; and

- to establish a secure, nonpublic database at FinCEN for beneficial ownership information.

The Conference Report (at page 4,456 of the 4,517-page report) included some interesting language on the purposes of the Act:

“One overarching improvement now included in the conference agreement is to broaden the mission of the BSA to specifically safeguard national security as well as the more traditional investigatory pursuits of law enforcement … Currently, there is no clear statutory mandate for BSA stakeholders – law enforcement, financial regulators, and financial institutions – to provide routine, standardized feedback to one another for the purpose of improving the effectiveness of BSA AML programs … [and there is a] clear mandate for innovation.”

Changes to the Purpose of the Bank Secrecy Act – 31 USC s. 5311

The additions to the “purpose” section of the BSA may be the single biggest change to the current AML/CFT regime. As set out below, section 5311 of title 31 is the declaration of purpose. From 1970 through 2001, that purpose was simply “to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations, or proceedings.” The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 added a clause relating to international terrorism: the amended section provided that the purpose was “to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations, or proceedings, or intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.”

As can be seen below, the original (post-2001) purpose has been changed in three ways. First, changing reports “where they have a high degree of usefulness” to reports “that are highly useful”. [8] Second, those reports are now to be used in regulatory risk assessments. And third, it appears that BSA reports are intended for all terrorism purposes, not just international terrorism (domestic and international). The new section 5311 declaration adds four new purposes: strong private sector programs, tracking dirty money, conduct national risk assessments to protect the financial system and national security generally, and to encourage public private sector information sharing. And note the language in subsection (5) where “service providers” has been added, a recognition of the growing regtech/fintech industry. The Declaration of Purpose now provides that:

It is the purpose of this subchapter (except section 5315) to –

- require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness that are highly useful in – (A) criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations, risk assessments, or proceedings; or (B) intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism;

- prevent the laundering of money and the financing of terrorism through the establishment by financial institutions of reasonably designed risk based programs to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism;

- facilitate the tracking of money that has been sourced through criminal activity or is intended to promote criminal or terrorist activity;

- assess the money laundering, terrorism finance, tax evasion, and fraud risks to financial institutions, products, or services to – (A) protect the financial system of the United States from criminal abuse; and (B) safeguard the national security of the United States; and

- establish appropriate frameworks for information sharing among financial institutions, their agents and service providers, their regulatory authorities, associations of financial institutions, the Department of the Treasury, and law enforcement authorities to identify, stop, and apprehend money launderers and those who finance terrorists.

Changes to the AML/CFT Program Requirements – 31 USC s. 5318(h)

Section 5318 of title 31 is the catch-all “compliance” section of the BSA. In addition to the SAR reporting requirements in subsection 5318(g), and the Customer Identification Program requirements in subsection 5318(l), this section has the requirements for financial institutions’ AML/CFT programs in subsection 5318(h).

Subsection (h)(1) is the so-called “four pillars” or minimum requirements of a program: “In order to guard against money laundering through financial institutions, each financial institution shall establish anti-money laundering programs, including, at a minimum –

(A) the development of internal policies, procedures, and controls;

(B) the designation of a compliance officer;

(C) an ongoing employee training program; and

(D) an independent audit function to test programs.

Subsection (h)(1) is changed to reflect the CFT aspects of the regime. It now requires financial institutions to “establish AML and countering the financing of terrorism programs in order to guard against money laundering and the financing of terrorism”. The minimum standards, or “four pillars”, did not change.

Perhaps this was a lost opportunity to reconcile the four pillar program requirements in 31 USC s. 5318(h) with the five pillar program requirements in 31 CFR s. 1010.210 and with the four pillar program requirements in 12 CFR s. 21.21.[9]

Subsection (h)(2) gives the Treasury Secretary the power to prescribe rules (regulations) for the AML program standards. This subsection is dramatically altered with the addition of factors that the Secretary shall take into consideration. And a new subsection, (h)(4), is added that sets out a new requirement that the Government shall establish national priorities, updated every four years, that need to be incorporated into institutions’ AML/CFT programs and, notably, how those national priorities are incorporated will be examined by the regulatory agencies:

(h)(2)(B) – Factors that the Secretary shall take into account when prescribing minimum standards and regulators shall take into account in supervising and examining: (i) financial institutions are spending private funds for public and private benefit; (ii) key policy goals of the US are extending financial services to the underbanked and facilitating global remittances while preventing criminals from abusing the system; (iii) effective AML and CFT programs safeguard national security and generate public benefit; (iv) AML and CFT programs should be (I) “reasonably designed to assure and monitor compliance with the requirements of this subchapter and regulations promulgated under this subchapter; and (II) risk-based, including that more attention and resources of financial institutions should be directed toward higher-risk customers and activities, consistent with the risk profile of a financial institution, rather than toward lower-risk customers and activities.”

(h)(4) – Priorities: (A) within 180 days the Government shall establish AML And CFT priorities; (B) those priorities will be renewed every 4 years; (C) these priorities will be aligned with national security priorities; (D) FinCEN will promulgate regulations within 180 days of (A); (E) financial institutions shall incorporate those priorities into their AML/CFT programs and will be supervised and examined thereon.

Changes to FinCEN’s Duties, Powers, and Scope – 31 USC s. 310

Part 3 of title 31 sets out the organization, function, powers, and duties of the Treasury Department generally, and each of the bureaus or divisions within the Treasury Department. Section 310 of Part 3 is the section for the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN.

As can be seen below, the duties and powers of the FinCEN director set out in section 310(b) have been greatly expanded. The current subsection has nine duties – (A) through (I) – and a catch-all (J). That catch-all has been moved down to (O) as five new duties and powers have been added – (J) through (N):

(A) Provide advice and make recommendations to the Under Secretary for Enforcement

(B) Maintain a government-wide database of BSA reports

(C) Analyze and disseminate intel from that database

(D) Maintain a communications center for law enforcement

(E) Furnish research, analytical, and informational services to the private and public sectors

(F) Assist law enforcement and regulators in combatting informal value transfer systems

(G) Support the tracking of foreign assets

(H) Coordinate with foreign FIUs

(I) Administer the requirements of the BSA

(J) Promulgate regulations to implement the exam and supervision priorities of BSA/AML programs

(K) Communicate regularly with the private sector, regulators, and law enforcement to explain the Government’s AML/CFT exam and supervision priorities

(L) Give and receive feedback to and from the private sector and State bank and credit union supervisors

(M) Maintain money laundering and terrorist financing experts to support federal civil and criminal investigations

(N) Maintain emerging technology experts

(O) Such other duties and powers as the Secretary may delegate

Subsection 310(c) on FinCEN’s requirements relating to maintenance and use of its data banks, did not change. However, the AML Act added seven new subsections that greatly expand FinCEN’s purpose, reach, authority, and staffing/budget:

- 310(d) – FinCEN Exchange (added by s. 6103, which (i) codifies in the statute the Exchange that FinCEN established two years ago; and (ii) requires FinCEN to report to Congress on the effectiveness of the Exchange within one year then once every two years for five years)

- 310(e) – Special hiring authority for terrorism and intel (added by s. 6105, this gives both FinCEN and its parent agency, the Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, or OTFI, the ability to makes certain hires without going through the usual federal government steps. Like section 6305, FinCEN and OTFI must report to Congress within a year)

- 310(f) – adds at least 6 FinCEN Domestic Liaisons (added by s. 6107)

- 310(g) – adds Chief of Domestic Liaison (added by s. 6107, which creates a Deputy Director of Domestic Liaison reporting to the FinCEN Director, with an Office of Domestic Liaison located in Washington DC. The six Domestic Liaisons will report regionally, and can be co-located with Federal Reserve offices, as needed. Same requirements to report to Congress.)

- 310(h) – adds at least 6 Foreign FIU Liaisons (added by s. 6108, these positions will be similar to Treasury attaches and will work with Egmont and FATF)

- 310(i) – FOIA protection of information shared with international FIUs (added by s. 6109)

- 310(j) – requires analytical experts for FinCEN’s “Analytical Hub” (added by s. 6304)

- 310(l) – Appropriation for FY2021 of $136 million, adding $10 million by s. 6509

In addition to the changes set out in 31 USC s. 310, the AML Act added some general provisions. Section 6203(a) of the AML Act provides that FinCEN shall solicit feedback from a cross section of BSA Officers on their financial institution’s SARs and trends observed by FinCEN, and FinCEN will provide that information to the institution’s regulator. Section 6203(b) of the AML Act requires that FinCEN shall periodically disclose to each financial institution, in summary form, information on SARs filed that proved useful to law enforcement and to DOJ. And section 6208 creates a new position of BSA Innovation Officer reporting directly to Director of FinCEN (similar positions for the Federal functional regulators).

Other Changes to the Bank Secrecy Act – 31 USC Subchapter II, ss. 5311 – 5322

31 USC s. 5321 Civil Penalties – section 6309 adds new subsection 31 USC 5321(f) and provides for enhanced or additional penalties for repeat offenders of 3x the profit gained or loss avoided as a result of the violation or 2x the maximum penalty. Section 6310 adds new subsection 31 USC 5321(g) and bans those who have committed “egregious violations”, defined as criminal convictions where the maximum sentence is more than one year and civil violations where the individual willfully committed the violation and the violation facilitated money laundering or terrorist financing, from serving on a financial institution board for ten years.

Section 6312 adds subsection 31 USC s. 5322(e) to the criminal penalties section. It requires the return of any profit gained by reason of the criminal violation and, if the offender was a partner, director, officer, or employee, they must repay the institution any bonus paid during the calendar year in which the violation occurred or the year thereafter. I expect there to be some questions raised about this subsection around why the offending institution is re-paid bonuses, and situations where directors are not paid bonuses (they rarely are).

Expanded Whistleblower Awards and Protections – 31 USC s. 5323

Section 6314 extensively altered and expanded the whistleblower section of title 31. The current section only allows for “informants” to receive rewards of between $12,500 and $150,000, and there is nothing in the section about protecting informants (whistleblowers) from retaliation. This new section increases the rewards to up to 30% of the penalty, and includes detailed provisions on protecting whistleblowers.

Modernizing the AML/CFT System Generally

Title LXII (sections 6201 – 6216) and title LXV (sections 6502 – 6508) collectively are intended to, and do, modernize the AML/CFT system.

- 6201 – The Attorney General shall report annually on the use of BSA reports, including whether the reports contain “actionable information” that leads to further proceedings by law enforcement, intelligence community, or national security; and extent to which arrests, indictments, convictions result. Note the term “actional information”: is it different from information that provides a “high degree of usefulness” (the current language of section 5311) or is “highly useful” (the new language of section 5311)?

- Sections 6204, 6205 call for a review of the contents, forms, and thresholds of CTRs and SARs. I have argued against raising the SAR or CTR thresholds[10]

- Section 6209 adds 31 USC 5318(o) – a review of whether and how Model Validation applies to AML/CFT. Following that review, the new standards would be put into a regulation and incorporated in the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual. This could be an impactful change: the current pedantic application of strict model validation requirements is a drain and distraction on effective financial crime programs. As I recently wrote:

Revising existing model-risk-management guidance to AML systems assumes there is existing model-risk-management guidance to AML systems. But there isn’t any such guidance. The model risk management guidance – from 2000 and revised in 2011 – was never intended to be applied against AML systems. None of the five editions of the FFIEC Exam Manual, the four after the original 2000 guidance and the one following the 2011 revision of the guidance, make any reference to the model risk management guidance. If AML systems are to be subject to strict model governance, then that governance must be set out in binding regulation subject to public review and comment. And AML systems should not be subject to the same strict model governance requirements as Value-At-Risk models, liquidity models, or even consumer lending models. Nothing has more adversely impacted the ability of large financial institutions to fight financial crime, human trafficking, kleptocracy, nuclear proliferation, etc., as the strict, pedantic, dogmatic application of model risk governance. [11]

- Section 6213 adds 31 USC s. 5318(p), thereby codifying the October 2018 interagency statement on sharing BSA resources

- Section 6214 encourages information sharing and Public/Private Partnerships, and requires the Secretary to convene a supervisory team of agencies, private sector experts, etc., to examine strategies to increase such cooperation.

- Section 6215 requires the GAO to publish a de-risking analysis within one year, followed by a strategy from the Secretary one year thereafter. This section includes a definition of de-risking: “actions taken by a financial institution to terminate, fail to initiate, or restrict a business relationship with a customer, or a category of customers, rather than manage the risk associated with that relationship consistent with risk-based supervisory or regulatory requirements, due to drivers such as profitability, reputational risk, lower risk appetites of banks, regulatory burdens or unclear expectations, and sanctions regimes.”

- Section 6216 requires a review of regulations and guidance within one year.

- Title LXV calls for multiple GAO and Treasury studies:

- Study on beneficial ownership information reporting requirements (section 6502 and both GAO and Treasury shall report separately within two years),

- Study on feedback loops (section 6503 and GAO to report within eighteen months),

- Study on CTRs (section 6504 and GAO to report no later than December 31, 2025)[12],

- Study on trafficking networks (section 6505 and GAO to report within one year),

- Study on trade-based money laundering (TBML) (section 6506 and Treasury to report within one year)[13],

- Study on money laundering by China (section 6507 and Treasury to report within one year), and

- Study on the efforts of authoritarian regimes to exploit the financial system of the US (Treasury and Justice to conduct the study within one year and report within two years).

- Section 6305 is an assessment of (actually, it contemplates the creation of) BSA No-Action Letters. Within 180 days of the passage of the Act, the Director must report to the House Financial Services Committee and the Senate Banking Committee on (i) whether to establish a process to issue no-action letters in response to inquiries on the application of the BSA or any AML/CFT law or regulation to specific conduct, including a request for a statement as to whether FinCEN or any relevant Federal functional regulator intends to take an enforcement action against the person with respect to such conduct. This would be a major change. Since 1987 FinCEN has an “Administrative Ruling” regime, whereby a financial institution may submit an Administrative Ruling request seeking FinCEN’s interpretation of a particular BSA regulation to the facts set out in the request. FinCEN’s response, the Administrative Ruling itself, has precedential value and may be relied upon by others similarly situated only if the ruling is published on FinCEN’s website. According to a notice published in the Federal Register on December 11, 2020, FinCEN received 98 Administrative Ruling requests from 2018-2020. According to FinCEN’s website, it only published 5 of those 98 requests (so 93 of the 98 are not of value to other institutions). And it takes months, sometimes years, for FinCEN to issue these rulings. For all of these reasons, a “No Action Letter” regime may be more effective than the current Administrative Ruling regime.

Changes to the Reporting of Suspicious Transactions – 31 USC s. 5318(g)

Reporting of suspicious transactions, or Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs), is set out in subsection (g) of section 5318. The AML Act changes the SAR regime in a number of ways, including .

5318(g)(1) – gives the Secretary the ability to issue regulations to require financial institutions to report suspicious transactions.

(g)(2) – Notification Prohibited – A filing financial institution and any officer, director, or employee of a filing financial institution cannot notify or disclose to any person involved in a reported suspicious transaction that the transaction has been reported or otherwise reveal any information that would reveal that the transaction has been reported (this language was added by section 6212 and codifies what was in the regulation and regulatory guidance).

(g)(3) – Liability for disclosure of SAR

(g)(4) – Single designee for SARs (FinCEN)

(g)(5) – Establish streamlined, including automated, processes to, as appropriate, permit the filing of noncomplex categories of SARs (added by section 6202, this is similar to provisions that were in FinCEN’s September 16, 2020 Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking)

(g)(6) – FinCEN shall share threat pattern and trend information at least semiannually to provide meaningful information about the preparation, use, and value of BSA reports. It shall include typologies, including data that can be adapted in algorithms, if appropriate on emerging money laundering and terrorist financing threat patterns and trends (added by s. 6206, this appears to compel FinCEN to go back to its semi-annual SAR Activity Reports, which were discontinued in 2013)

(g)(7) – Rules of construction (added by s. 6206)

(g)(8) – Pilot program within one year to allow a US financial institution to share SAR-related information with its foreign branches and affiliates (added by s. 6212, this would close an anomaly in the law and regulation, where foreign banks operating in the United States could share SAR information with their home-country head office, but US banks could not share SAR information with their foreign branches and affiliates. There was an exception: prohibited jurisdictions are China and Russia, any state sponsor of terrorism, any jurisdiction subject to sanctions, and any jurisdiction determined by the Secretary that cannot reasonably protect the security and confidentiality of such information).

New Sections Have Been Added to the BSA (subchapter II of Title 31)

- 5333 – Safe harbor for “Keep Open Directives” (added by s. 6306, this section would require law enforcement to notify FinCEN of any “keep open request” made of a financial institution to keep an account “or transaction” open. Financial institutions are not required to comply)

- 5334 – Required annual training for Federal financial regulators’ examiners (added by s. 6307, one would have assumed that examiners would be required to be trained on the regulatory requirements they are examining. This new section requires annual training, and the training is to be done in consultation with FinCEN and all levels of law enforcement – federal, state, tribal, and local.)

- 5335 – Penalties for concealing PEPs’ source of funds (added by s. 6313, this new section applies to PEPs or Senior Foreign Political Figures where the aggregate value of monetary transactions is not less than $1 million and the transaction(s) affect(s) interstate or foreign commerce. It provides that no person shall knowingly conceal, falsify, or misrepresent, ot attempt to do so, a material fact concerning the ownership or control of assets involved in a monetary transactions. And, if the transaction(s) involve(s) an entity found to be of primary money laundering concern under section 5318A, the same person cannot conceal the source of funds. This section will be complex to administer.)

- 5336 – Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting requirements (added by s. 6403 – see below)

Two New BSAAG Subcommittees

Section 1564 of the Annunzio-Wylie AML Act of 1992 created the BSA Advisory Group (BSAAG). The AML Act of 2020 adds two subcommittees: the Subcommittee on Innovation and Technology added by s. 6207 (adding subsection 1564(d)) and the Subcommittee on Information Security & Confidentiality added by s. 6302 (adding subsection 1564(e)). Both subcommittees have a five-year “sunset” clause, or terminate in five years, unless the Secretary renews them for as many one-year terms as the Secretary chooses. The mandate of the Subcommittee on Innovation and Technology is to study and make recommendations on how to “most effectively encourage and support technological innovation [and reduce] obstacles to innovation that may arise from existing regulations, guidance, and examination practices.” This subcommittee will also include the BSA Innovation Officers authorized by section 6208.

New Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements

The New Requirements

Title LXIV – sections 6401-6403 adds 31 USC s. 5336

Section 6402 is the “Sense of Congress” section. That section provides, in part, that the beneficial ownership information “will be directly available only to authorized government authorities” and the database is intended to be “highly useful to national security, intelligence, and law enforcement agencies and Federal functional regulators”. There is no mention of making the information directly available to financial information or even having it benefit financial institutions. As seen from Congressman McHenry’s comments (see Appendix A), that was the intent: the registry is quite limited.

Under the AML Act:

- Beneficial Owner is defined as an individual who directly or indirectly exercises substantial control or owns or controls not less than 25%.

- Reporting Company is defined as not including companies with more than 20 FTE, more than $5 million in gross revenues, and with an operating presence in the United States.

- Existing companies have two years to report. New companies shall report at the time of formation. Changes in beneficial ownership must be reported within a year.

- Financial institutions can only query the database about a company with the consent of that company. The existing beneficial ownership rule of May 11, 2016 will be brought into conformance with this section within a year.

Why were the beneficial ownership registry provisions watered down so much? The answer to that question could be found in comments made by Congressman Patrick McHenry, (R. NC 10). His floor comments from December 8, 2020, as captured in the House Congressional Record, are included in Appendix A. His comments bear particular weight, as Congressman McHenry is the Ranking Member on the House Financial Services Committee.

The Impact on the Current Beneficial Ownership Rule

Congressman McHenry commented that this new reporting rule “rescinds the current beneficial ownership reporting regime set out in 31 CFR 1010.230 (b)–(j), which is costly and burdensome to small businesses.” However, it may not be as cut-and-dried as he states. The section that Rep. McHenry is referring to is 6403(d). That section provides:

Section 6403(d) REVISED DUE DILIGENCE RULEMAKING.

(1) IN GENERAL. – Not later than 1 year after the effective date of the regulations promulgated under section 5336(b)(4) of title 31, United States Code, as added by subsection (a) of this section, the Secretary of the Treasury shall revise the final rule entitled “Customer Due Diligence Requirements for Financial Institutions” (81 Fed. Reg. 29397 (May 11, 2016)) to –

(A) bring the rule into conformance with this division and the amendments made by this division;

(B) account for the access of financial institutions to beneficial ownership information filed by reporting companies under section 5336, and provided in the form and manner prescribed by the Secretary, in order to confirm the beneficial ownership information provided directly to the financial institutions to facilitate the compliance of those financial institutions with anti-money laundering, countering the financing of terrorism, and customer due diligence requirements under applicable law; and

(C) reduce any burdens on financial institutions and legal entity customers that are, in light of the enactment of this division and the amendments made by this division, unnecessary or duplicative.

(2) CONFORMANCE.

(A) IN GENERAL. – In carrying out paragraph (1), the Secretary of the Treasury shall rescind paragraphs (b) through (j) of section 1010.230 of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations upon the effective date of the revised rule promulgated under this subsection.

(B) RULE OF CONSTRUCTION. – Nothing in this section may be construed to authorize the Secretary of the Treasury to repeal the requirement that financial institutions identify and verify beneficial owners of legal entity customers under section 1010.230(a) of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations.

(3) CONSIDERATIONS. – In fulfilling the requirements under this subsection, the Secretary of the Treasury shall consider—

(A) the use of risk-based principles for requiring reports of beneficial ownership information;

(B) the degree of reliance by financial institutions on information provided by FinCEN for purposes of obtaining and updating beneficial ownership information;

(C) strategies to improve the accuracy, completeness, and timeliness of the beneficial ownership information reported to the Secretary; and

(D) any other matter that the Secretary determines is appropriate.

The result of this is that the Secretary shall rescind the current beneficial ownership rule but can replace it with a rule that is similar, if not identical to the current beneficial ownership rule. The current beneficial ownership rule provides financial institutions with more information on more legal entities sooner and requires them to use that information for not only onboarding due diligence, including customer risk rating, but ongoing due diligence (investigations of potential suspicious activity). It also gives financial institutions immediate access to existing legal entities’ beneficial ownership information where those entities open new accounts. This new beneficial ownership information registration requirement only includes the smallest legal entities, existing legal entities have two years to provide their owners’ information, and, most importantly, financial institutions have limited access to the registry as they need their customer’s approval to access the customer’s information. The differences between the existing rule and new law are recognized in subsection (B), which directs the Secretary to “account for the access of financial institutions to beneficial ownership information filed by reporting companies under section 5336 … in order to confirm the beneficial ownership information provided directly to the financial institutions to facilitate the compliance of those financial institutions with” AML, CFT, and CDD requirements.

Division H – Other Matters, Title XCVII, Subtitles A, B

- Subtitle A – Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Rewards Act

- Subtitle B – Combating Russian Money Laundering Act

Appendix A – Corporate Transparency Act – Congressional Comments

House Congressional Record from December 8, 2020 CREC-2020-12-08-pt1-PgH6919-3.pdf (congress.gov) at pages H6932-6933 (bold red font has been added for emphasis, and the footnote has been added from the original text):

Mr. MCHENRY. Mr. Speaker, I rise in support of the conference report to the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2021. Combating illicit finance and targeting bad actors is a nonpartisan issue. However, Congress’ actions must be thoughtful and data driven. An example of this is H.R. 2514, the COUNTER Act, which is included in this conference report. Division G is a compilation of bipartisan policies that will modernize and reform the Bank Secrecy Act and anti-money laundering regimes. These policies will strengthen the Department of Treasury’s financial intelligence, anti-money laundering, and counter terrorism programs.

I would like to thank Chairman CLEAVER and Ranking Member STIVERS for their work on this bill and the language included in Division G. In addition to Division G, the conference report contains an amendment replacing the text of H.R. 2513, the Corporate Transparency Act, with new legislation. H.R. 2513, which passed the House on October 22, 2019, and again as an amendment to H.R. 6395 on July 21, 2020, attempted to establish a new beneficial ownership information reporting regime to assist law enforcement in tracking down terrorists and other bad actors who finance terrorism and illicit activities. But, it did so to the detriment of America’s small businesses.

Beneficial ownership information is the personally identifiable information (PII) on a company’s beneficial owners. This information is currently collected and held by financial institutions prior to a company gaining access to our financial system.

However, bad actors and nation states, such as China and Russia, are becoming more proficient in using our financial system to support illicit activity. As bad actors become more sophisticated, so to must our tools to deter and catch them. One such tool is identifying the beneficial owners of shell companies, which are used as fronts to launder money and finance terrorism or other illicit activity. Beneficial ownership information assists law enforcement to better target these bad actors.

Although well-intentioned, H.R. 2513 had numerous deficiencies in its reporting regime. First, H.R. 2513 placed numerous reporting and costly reporting requirements on small businesses. It lacked protections to properly protect small businesses’ personal information stored with a little-known government office within the Department of Treasury—known as FinCEN. The bill authorized access to this sensitive information without any limitation on who could access the information and when it could be accessed. Finally, it failed to hold FinCEN accountable for its actions.

The text of H.R. 2513 is replaced with new language that I negotiated, along with Senate Banking Committee Chairman CRAPO. This substitute, which is reflected in Division F of the conference report, is a significant improvement over the House-passed bill in three key areas.

First, Division F limits the burdens on small businesses. Unlike H.R. 2513, the language included in the conference report protects our nation’s small businesses. It prevents duplicative, burdensome, and costly reporting requirements for beneficial ownership data from being imposed in two ways. It rescinds the current beneficial ownership reporting regime set out in 31 CFR 1010.230 (b)–(j), which is costly and burdensome to small businesses. Rescinding these provisions ensures that it cannot be used in a future rule to impose another duplicative, reporting regime on America’s small businesses. In addition, Division F requires the Department of Treasury to minimize the burdens the new reporting regime will have on small businesses, including eliminating any duplicative requirements.

House Republicans ensured the directive to minimize burdens on small businesses is fulfilled. Division F directs the Secretary of the Treasury to report to the House Committee on Financial Services and the Senate Committee on Banking annually for the first three years after the new rule is promulgated. The report must assess: the effectiveness of the new rule; the steps the Department of Treasury took to minimize the reporting burdens on reporting entities, including eliminating duplicative reporting requirements, and the accuracy of the new rule in targeting bad actors. The Department of Treasury is also required to identify the alternate procedures and standards that were considered and rejected in developing its new reporting regime. This report will help the Committees understand the effectiveness of the new rule in identifying and prosecuting bad actors. Moreover, it will give the Committees the data needed to understand whether the reporting threshold is sufficient or should be revised.

Second, Division F includes the strongest privacy and disclosure protections for America’s small businesses as it relates to the collection, maintenance, and disclosure of beneficial ownership information. The new protections set out in Division F ensure that small business beneficial ownership information will be protected just like an individual’s tax return information. The protections in Division F mirror or exceed the protections set out in 26 U.S.C. 6103, including:

- Agency Head Certification. Division F requires an agency head or designee to certify that an investigation or law enforcement, national security or intelligence activity is authorized and necessitates access to the database. Designees may only be identified through a process that mirrors the process followed by the Department of Treasury for those designations set out in 26 U.S.C. 6103.

- Semi-annual Certification of Protocols. Division F requires an Agency head to make a semi-annual certification to the Secretary of the Treasury that the protocols for accessing small business ownership data ensure maximum protection of this critically important information. This requirement is non-delegable.

- Court authorization of State, Local and Tribal law enforcement requests. Division F requires state, local and tribal law enforcement officials to obtain a court authorization from the court system in the local jurisdiction. Obtaining a court authorization is the first of two steps state, local and tribal governments must take prior to accessing the database. Separately, state, local and tribal law enforcement agencies must comply with the protocols and safeguards established by the Department of Treasury.

- Limited Disclosure of Beneficial Ownership Information. Division F prohibits the Secretary of Treasury from disclosing the requested beneficial ownership information to anyone other than a law enforcement or national security official who is directly engaged in the investigation.

- System of Records. Division F requires any requesting agency to establish and maintain a system of records to store beneficial ownership information provided directly by the Secretary of the Treasury.

- Penalties for Unauthorized Disclosure. Division F prohibits unauthorized disclosures. Specifically, the agreement reiterates that a violation of appropriate protocols, including unauthorized disclosure or use, is subject to criminal and civil penalties (up to five years in prison and $250,000 fine).

Third, Division F contains the necessary transparency, accountability and oversight provisions to ensure that the Department of Treasury promulgates and implements the new beneficial ownership reporting regime as intended by Congress. Specifically, Division F requires each requesting agency to establish and maintain a permanent, auditable system of records describing: each request, how the information is used, and how the beneficial ownership information is secured. It requires requesting agencies to furnish a report to the Department of Treasury describing the procedures in place to ensure the confidentiality of the beneficial ownership information provided directly by the Secretary of the Treasury.

Separately, Division F requires two additional audits. First, it directs the Secretary of Treasury to conduct an annual audit to determine whether beneficial ownership information is being collected, stored and used as intended by Congress. Separately, Division F directs the Government Accountability Office to conduct an audit for five years to ensure that the Department of Treasury and requesting agencies are using the beneficial ownership information as set out in Division F. This is the same audit that GAO conducts as it relates to the Department of Treasury’s collection, maintenance and protection of tax return information. This information will ensure that Congress has independent data on the efficacy of the reporting regime and whether confidentiality is being maintained.

Division F also requires the Department of Treasury to issue an annual report on the total number of court authorized requests received by the Secretary to access the database. The report must detail the total number of court authorized requests approved and rejected and a summary justifying the action. This report to Congress will ensure the Department of Treasury does not misuse its authority to either approve or reject court authorized requests.

Finally, Division F requires the Director of FinCEN, who is responsible for implementing this reporting regime, to testify annually for five years. This testimony is critical. For far too long FinCEN has evaded any type of congressional check on its activities. Yet, it has amassed a great deal of authority. Now, Congress will shine a light on its operations. It is my expectation that FinCEN will provide Congress with hard data on its effectiveness in targeting bad actors, including the effectiveness of this new authority to collect, maintain, and use beneficial ownership information.

One final comment about the importance of FinCEN’s annual testimony. In the months leading up to the House’s consideration of H.R. 2513 last October, I sought data from FinCEN and from the Treasury Department, along with the Department of Justice, to better understand the need for this legislation. No such data was forthcoming. Rather, FinCEN gave anecdotes of very scary stories to justify the need for a new reporting regime. It is my expectation that FinCEN will provide Congress with the necessary data to justify this new reporting regime and the burdens it is placing on legitimate companies. I will conclude by thanking Chairwoman MALONEY for her work over the last twelve years on this issue and her willingness to work with me to strengthen this bill. I believe we have a better product. I urge my colleagues to support the conference agreement.

Endnotes

[1] https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20201207/CRPT-116hrpt617.pdf

[2] The NDAA has broad, bipartisan support in both the House and the Senate. If the President vetoes the bill, as he has threatened to do, Congress can override the veto with a two-thirds super-majority vote in both chambers. More than two-thirds of the members of each chamber voted in favor of that chamber’s version of the bill. The Conference Report is the agreed-upon reconciliation of the two versions.

[3] See footnote 7 for an example of this anomaly of changing the title 31 laws and regulations but not the corresponding title 12 laws and regulations.

[4] US laws are available at https://uscode.house.gov

[5] In an article I published on October 28, 2019, I referred to the sometimes conflicting nature of these titles as “the clash of the titles”. See The Current BSA/AML Regime is a Classic Fixer-Upper … and Here’s Seven Things to Fix – RegTech Consulting, LLC

[6] Regulations are available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/cfr/2020

[7] There are also two titles in Division H (“Other Matters”) that also impact financial crimes, specifically kleptocracy and Russian money laundering. Those are described below.

[8] Records and reports that have a “high degree of usefulness” were also referenced in the two parts of title 12 – 12 USC s. 1829b and 12 USC Part 21, sections 1951-1959 – that, with 31 USC sections 5311-5314, 5316-5332, make up the Bank Secrecy Act. The AML Act is changing “high degree of usefulness” to “highly useful” in title 31, but not in title 12. That may be an oversight.

[9] In addition, Congress could have, but chose not to treat the Customer Identification Program, or CIP requirements, as a new fifth (or sixth) pillar or minimum standard. Subsection 5318(i) is the “customer identification program” section. It requires financial institutions to identify and verify accountholders, and for the Secretary to implement regulations for the minimum standards in doing so. The regulations set out whether and to what extent the eleven different types of financial institutions are to implement a formal customer identification program (for banks, broker dealers, mutual funds, and futures commission merchants in 31 CFR 1020, 1023, 1024, and 1026, respectively), or to implement some form of customer verification as part of their overall AML program (for casinos, MSBs, insurance companies, loan or finance companies, and government supervised entities in 31 CFR 1021, 1022, 1025, 1029, and 1030, respectively). Two of the eleven types of financial institutions, dealers in precious metals and credit card system operators, do not have to identify or verify the identity of customers. The result is that most financial institutions must have both an AML program and a Customer Identification Program: Congress had the opportunity to consolidate these two programs into one overall program but chose not to. It was a lost opportunity to further streamline the regulatory regime.

[10] See FinCEN Files – Reforming AML Regimes Through TSV SARs (Tactical or Strategic Value Suspicious Activity Reports) – RegTech Consulting, LLC

[11] FinCEN’s Proposed AML Program Effectiveness Rule – Comments of RegTech Consulting LLC – RegTech Consulting, LLC

[12] This was an interesting timeline: a GAO study on the effectiveness of the CTR regime, the utility of CTRs, and an analysis of the effects of raising the reporting threshold must begin no later than January 1, 2025 – four years from the passage of the AML Act! – and must be reported no later than December 31, 2025.

[13] Section 6506 is the only “study and report” section that specifically provides that (in this case) the GAO can contract out the study.