“A good deal of hysteria, some of it reflexive, much of it recreational”

The media, social media, politicians, and pundits are reacting loudly and passionately about the President’s decision to weigh in on the sentencing of Roger Stone, the resignations of four Assistant United States Attorneys involved in the case, and the decision of the Department of Justice to submit a revised sentencing recommendation. And the hysteria should continue for the foreseeable future, with the sentencing of Mr. Stone now set for February 20th.

The media, social media, politicians, and pundits are reacting loudly and passionately about the President’s decision to weigh in on the sentencing of Roger Stone, the resignations of four Assistant United States Attorneys involved in the case, and the decision of the Department of Justice to submit a revised sentencing recommendation. And the hysteria should continue for the foreseeable future, with the sentencing of Mr. Stone now set for February 20th.

Whether you are outraged or relieved about what is happening in this case, your outrage or relief should at least be informed.

In an essay published on May 10, 2004 in the Wall Street Journal’s Opinion section titled “The Spirit of Liberty: Before Attacking the Patriot Act, Try Reading It”, then chief judge of the U. S. District Court, Southern District of New York Michael Mukasey reminded us that if we were to express opinions on something, those opinions should at least be informed. Judge Mukasey was writing about the USA PATRIOT Act, passed in October 2001 in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a statute which had “become the focus of a good deal of hysteria, some of it reflexive, much of it recreational.” Judge Mukasey wrote that “[l]ike any other act of Congress, the Patriot Act should be scrutinized, criticized and, if necessary, amended. But in order to scrutinize and criticize it, it helps to read what is actually in it.”

The Roger Stone case isn’t an act of Congress, but the facts of the case – set out in the 288 documents on the docket – should be read and understood before one expresses an opinion. But 288 documents is a lot of reading. Three of those documents should, in my opinion, be enough to provide enough of a balanced background to allow someone to have and express an informed opinion: the Government’s original Sentencing Memorandum, Roger Stone’s Sentencing Memorandum, and the Government’s Revised Sentencing Memorandum. These are all publicly available documents. I’ll summarize them here. But first, a stop to explain the Sentencing Guidelines that are used in all federal criminal cases and which have been the subject of much of the rational, irrational, reflexive, or recreational hysteria around the Roger Stone case.

Federal Sentencing Guidelines – a Primer

The following is an excerpt from my April 2019 article on the College Admissions Scandal – College Admissions Scandal – RegTech Consulting Article April 16, 2019.

The Federal Sentencing Guidelines are intended to provide “guideline ranges that specify an appropriate sentence for each class of convicted persons determined by coordinating the offense behavior categories with the offender characteristic categories.” US Sentencing Commission Link

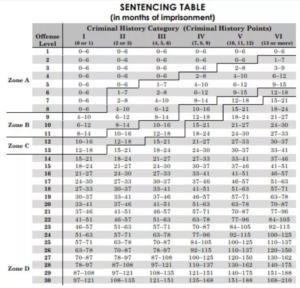

So there are two things to be considered: the defendant’s own criminal histories, if any, and the “offense level” of their crime, adjusted for various aggravating factors, and adjusted down for “acceptance of responsibility”. This gives an offense level of between 1 and 43, organized into four “zones”. The defendant’s criminal history is then considered, resulting in being placed into one of six criminal history categories. The result is a Sentencing Table with the seriousness of the crime on the Y axis and the seriousness of the criminal on the X axis. The court refers to, and can depart from, the ranges set out in the Table. A (partial) sentencing table (showing only the first 30 of the 43 offence levels) is seen below.

United States v. Roger J. Stone, U.S. District Court, District of Columbia Case 19CR00018 – Sentencing Scheduled for February 20, 2020

Government’s Original Sentencing Memorandum – Seeking imprisonment consistent with Sentencing Guidelines of 87-108 months

The Government’s original Sentencing Memorandum went through the history of the case. In January 2019 a federal grand jury indicted Roger Stone on seven criminal counts: one count of obstruction of a Congressional investigation (relating to his sworn testimony before the House Intelligence Committee), five counts of making false statements to Congress (“in his testimony before the House Intelligence Committee, Stone told the Committee five categories of lies”), and one count of witness tampering. In November 2019, after a lengthy trial, a jury convicted Roger Stone of all seven counts. The Memorandum also included a number of issues relating to the pre-trial conduct of Mr. Stone, and the court’s response to that conduct. An episode relating to an image Mr. Stone posted to Instagram of the judge with cross-hairs next to her head was included in the Memorandum.

The Government asked that “a sentence consistent with the applicable advisory Guidelines would accurately reflect the seriousness of his crimes and promote respect for the law.” At page 16 of its Memorandum, the Government set out the Guidelines Range based on an offense level of 29 and a Criminal History category of I (no criminal record), resulting in a range of imprisonment of 87 months to 108 months. That offense level of 29 was determined as follows:

14 for the base offense(s) level

+8 for threatening a witness

+3 for interference with the administration of justice

+2 for an offense that was extensive in scope, planning, or preparation

+2 for obstruction of justice

Roger Stone’s Sentencing Memorandum – Seeking probation below the Sentencing Guidelines of 15-21 months

Roger Stone’s attorneys’ Memorandum included a number of character references (letters) and focused on his exemplary personal life, a life they pointed out was very different than his public persona. They laid out a position that the sentencing guidelines should be based only on the base offense level of 14, without any enhancements, leaving a guideline range of 15 to 21 months, and that the Court should go below that range and sentence the defendant to a period of probation. They concluded ” the Court should impose a non-Guidelines sentence of probation with any conditions that the Court deems reasonable under the

circumstances.”

Government’s Amended Sentencing Memorandum (February 11) – Seeking imprisonment “far less than” Sentencing Guidelines of 87-108 months, but leaving it up to the Judge to decide how much less than

After the four Assistant US Attorneys withdrew from the case, new counsel from the Department of Justice filed an amended Sentencing Memorandum, setting out the Government’s position that:

“The prior filing submitted by the United States on February 10, 2020 (Gov. Sent. Memo. ECF No. 279) does not accurately reflect the Department of Justice’s position on what would be a reasonable sentence in this matter. While it remains the position of the United States that a sentence of incarceration is warranted here, the government respectfully submits that the range of 87 to 108 months presented as the applicable advisory Guidelines range would not be appropriate or serve the interests of justice in this case.”

And the Government concluded:

“The defendant committed serious offenses and deserves a sentence of incarceration that is “sufficient, but not greater than necessary” to satisfy the factors set forth in Section 3553(a). Based on the facts known to the government, a sentence of between 87 to 108 months’ imprisonment, however, could be considered excessive and unwarranted under the circumstances. Ultimately, the government defers to the Court as to what specific sentence is appropriate under the facts and circumstances of this case.”

Conclusion

You’ve read, or will read, the three sentencing memoranda. You have or will have a rudimentary understanding of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines and how they were applied in this case. From there, you can join the debate and express a reasonably learned opinion, backed by some knowledge of the facts. It is my opinion that everyone has a right to their opinion and to express that opinion, but it is their duty to express that opinion only after informing themselves of the facts and, to paraphrase Judge Mukasey, without resorting to reflexive, recreational hysteria.