The Scottsdale Research Institute case may be a significant step forward in the normalization of cannabis. And it may address one of the most vexing clinical cannabis catch-22 situations there is today.

Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act lists drugs that are both harmful and have no currently accepted medical use. Marijuana or cannabis was included in Schedule I since the passage of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, and has remained there, notwithstanding great public, political, and other pressure to reschedule or even deschedule it.

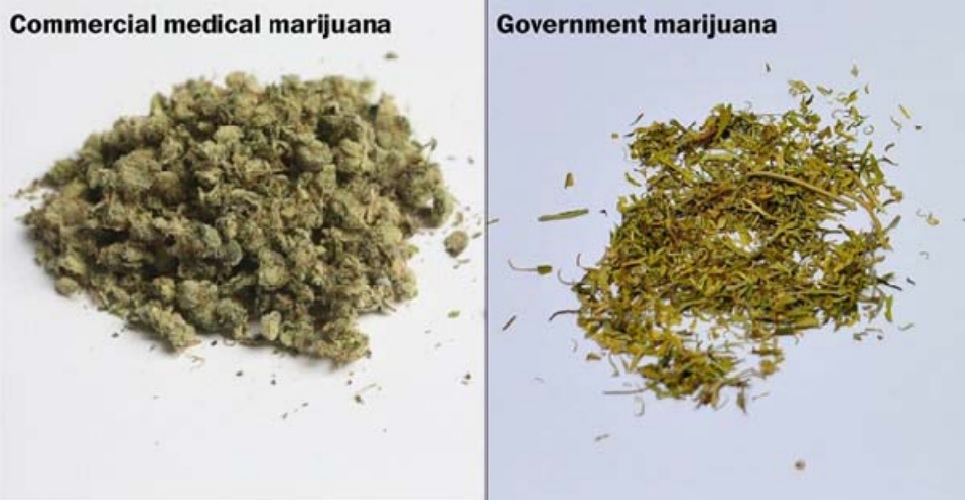

Congress has the ability to reschedule marijuana. Let’s assume that they’re not prepared to act anytime soon: that would take courage and compromise, two things that appear to be lacking in this Congress. But the DEA also has the ability to reschedule marijuana, but it has not done so, and various DEA publications have indicated that it won’t do so because of a dearth of clinical trials demonstrating currently accepted medical use, or medical efficacy. One of the reasons for the dearth of clinical trials is a lack of availability of approved research-grade cannabis. Under the Controlled Substance Act, the DEA controls who gets to product cannabis for clinical trials. Currently, there is one such approved facility, the University of Mississippi. And the cannabis produced by that facility is, by most accounts, not very good (the picture here is from the Scottsdale Research Institute court filing, mentioned below). So why aren’t there more facilities approved to grow cannabis for medical research?

The DEA controls that, too. From 1970 (when the CSA was passed and cannabis was included in Schedule I), dozens of applications to produce cannabis for medical research were filed, and none were approved. In late 2015 a federal law was passed that compelled the DEA to act on these applications – to approve or deny them – within 90 days. Again, dozens of applications have been filed. And none have been acted on.

An interesting case is now before the US Court of Appeals (District of Columbia) called In re: Scottsdale Research Institute, LLC, District of Columbia Court of Appeals, case No. 19-1120, where a medical research company is seeking to compel the DEA to act on its application to produce pharmaceutical-grade cannabis. The facts are important …

A doctor in Arizona, Dr. Suzanne Sisley, has the necessary federal approvals to run a clinical trial to determine whether cannabis is effective in treating veterans’ PTSD (as Dr. Sisley writes in her Declaration supporting the petition, she “struggled for seven years [from 2009 to 2016] to get approval from four different federal agencies to conduct clinical trials of cannabis as a treatment for PTSD symptoms in veterans.”). But she cannot begin those trials without pharmaceutical grade cannabis, which the only approved supplier cannot provide. In 2016 she (actually, her company and the appellant in this case, Scottsdale Research Institute, LLC, or “SRI”) submitted an application to grow her own cannabis for her clinical trials, but the DEA hasn’t acted on that application, notwithstanding the law that says it has to. Without pharmaceutical-grade cannabis to run her FDA-approved clinical trials, she was stuck. This petition, called a Writ of Mandamus, was brought to compel the DEA to act. Notably, the Writ of Mandamus does not seek to compel the DEA to grant the application to produce cannabis for research: as SRI writes in its petition, “mandamus here will not divest the agency of its discretion. It simply allows the process contemplated by the statute to begin, not end. The agency still maintains discretion to deny or delay the application.”

So let’s sum up:

- The DEA won’t consider rescheduling cannabis without clinical trials.

- Clinical trials require approved, pharmaceutical-grade cannabis.

- The DEA decides who produces pharmaceutical-grade cannabis.

- The only DEA-approved producer of pharmaceutical-grade cannabis cannot produce pharmaceutical-grade cannabis.

- Since 2016, the DEA has been required by law to either approve or reject applications to produce cannabis for medical research within 90 days of receiving the application.

- The DEA has received dozens of applications from entities seeking to produce pharmaceutical-grade cannabis.

- The DEA has neither approved nor rejected any of those applications in the 3+ years it has been compelled by law to do so.

- SRI is bringing a federal court action to compel the DEA to consider its application.

As Dr. Sisley and SRI’s petition to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals provides:

“Millions of Americans believe cannabis holds the key to ending their pain and suffering, making the need for clinical trials acute no matter the outcome of SRI’s clinical trials. If those studies show that thirty-eight states (and counting), doctors, legislators, and the American public are all wrong—i.e., that cannabis lacks medical utility—then we must know this now. Those using cannabis to treat conditions like PTSD may be jeopardizing their health and welfare. But in the more likely alternative— i.e., SRI’s studies prove that cannabis has medical value—DEA’s delay inexcusably deprives combat veterans and others of a treatment option necessary to ease their pain. Either way, more delay is unconscionable.”

The Court of Appeals issued a preliminary ruling on July 29th regarding SRI’s June 11th petition: the DEA has 30 days to file a response, and SRI then has 14 days to file a reply to that response. Notably, after receiving SRI’s 284-page petition, the Court of Appeals has limited the DEA’s response to 7,800 words, and SRI’s reply to 3,900 words. (This article is 800 words long, by the way).

I doubt that clinical trials will prove that cannabis lacks medical utility – but whether something has medical utility isn’t really the question. Many non-approved, and unapprovable, products have some medical utility, but can’t be safely used as federally-approved medicines. Let’s allow the clinical researchers to do their jobs. Let’s allow – perhaps we need to compel – federal regulatory agencies to do their jobs. And wherever and however this comes out at the end, at least we will know what safe and appropriate medical uses there are for cannabis, or components of cannabis.