For years, FinCEN has used a one-size-fits-all-SARs method of determining the costs and burden of filing Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs): a flat two hours, or 120 minutes. With a new-found ability to slice-and-dice its SAR data, FinCEN has now determined that the back half of the SAR filing process takes between 45 and 315 minutes, depending on the type of SAR. And it’s looking for feedback from the private sector on how to enhance this estimate.

Posted June 2, 2020

On May 26, 2020, FinCEN published a notice in the Federal Register titled “Proposed Updated Burden Estimate for Reporting Suspicious Transactions Using FinCEN Report 111 – Suspicious Activity Report”. This is a notice required under the Paperwork Reduction Act, or PRA: agencies are required to periodically assess and estimate the burdens and costs of their regulatory regimes.

This is a ground-breaking notice, for it is the first such notice where: (1) FinCEN has been able to analysis the SAR Database to quantitatively assess the numbers, characteristics, and types of SARs, by institution type, by type of work required to be done, and by what types of involved positions; and (2) perhaps just as important, FinCEN has shown a willingness to provide this information and to seek feedback from the private sector on other available information that could be incorporated into future analyses. FinCEN must be commended for both.

In prior PRA notices, FinCEN has simply estimated that the SAR filing process takes a total of two hours for each and every SAR filed. With this notice, FinCEN identified and attempted to capture burden and cost estimates for, five categories of SARs, two types of filing (batch and discrete), the six stages in the SAR filing process, and the four types of positions involved in the process.

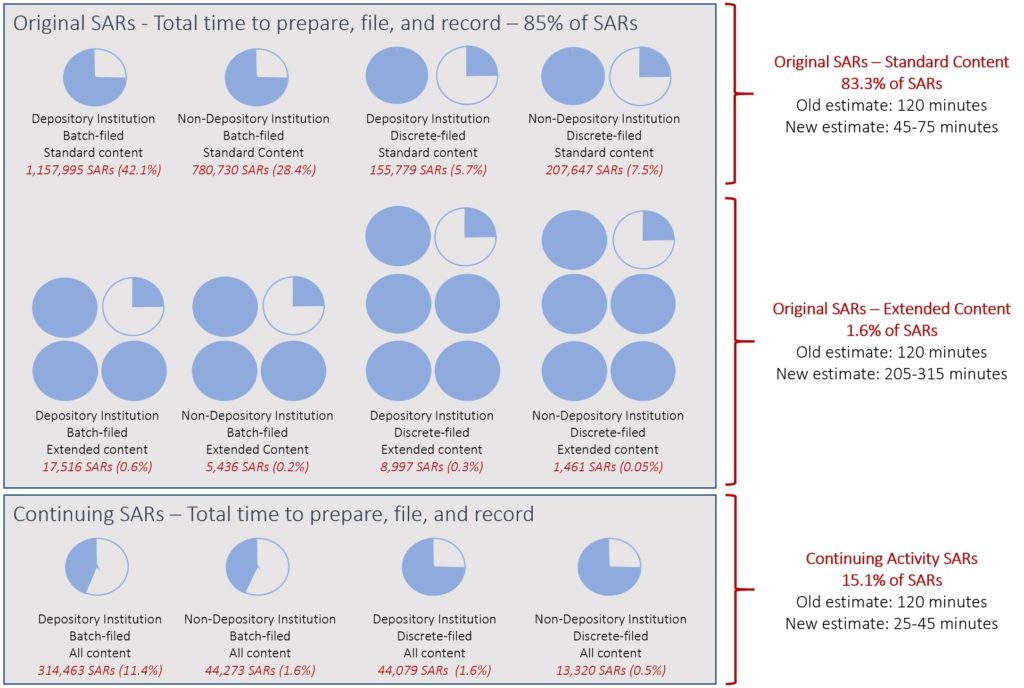

Five categories of SARs: (1) depository institutions’ (banks and credit unions) original SARs with standard content; (2) depository institutions’ original SARs with extended content; (3) non-depository institutions’ original SARs with standard content; (4) non-depository institutions’ original SARs with extended content; and (5) all filers’ continuing activity SARs. The standard and extended content analysis looked at combinations of (1) the number of named suspects; (2) the number of suspicious activities’ categories marked on the SAR form; (3) the length and make-up of the narrative; and (4) whether there was an attachment.

Six stages in the SAR filing process: (1) maintaining a monitoring system; (2) reviewing alerts; (3) transforming alerts into cases; (4) case review; (5) documentation of the SAR/no SAR determination; and (6) the SAR filing process. The current two-hour per SAR PRA estimate only considered the 6th stage: this notice added the 4th and 5th stage, and FinCEN acknowledged that it needs further data, and comments from the private sector, in order to include the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd stages.

Four types of people: (1) general supervision (oversight); (2) direct supervision; (3) clerical (SAR investigation); and (4) clerical (filing).

With this notice, FinCEN is changing its PRA burden estimate of 120 minutes per SAR to an estimate ranging from 25 minutes to 315 minutes per SAR for the last 3 of the 6 stages in the SAR filing process, and is inviting comments on these new estimates and on how to include and estimate the first 3 of the 6 stages.

Comments from the public are due by July 27, 2020.

Below is my analysis and commentary on the FinCEN notice. The text of the Notice is in regular font: my analysis and comments are in red italics.

Renewal Without Change of the Bank Secrecy Act Reports by Financial Institutions of Suspicious Transactions

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-26/pdf/2020-11247.pdf

Agency Information Collection Activities; Proposed Renewal; Comment Request;

AGENCY: Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), Treasury.

ACTION: Notice and request for comments.

SUMMARY: As part of its continuing effort to reduce paperwork and respondent burden, FinCEN invites comments on the proposed renewal, without change, of currently approved information collections relating to reports of suspicious transactions. Under the Bank Secrecy Act regulations, financial institutions are required to report suspicious transactions using FinCEN Report 111 (the suspicious activity report, or SAR). Although no changes are proposed to the information collections themselves, this request for comments covers a proposed updated burden estimate for the information collections.

This request for comments is made pursuant to the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995.

DATES: Written comments are welcome, and must be received on or before [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AFTER THE DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THIS DOCUMENT IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER.]

JRR Comment: Very simply, FinCEN is proposing updates to the way it estimates the burden – both time and cost – for preparing and filing Suspicious Activity Reports, and is seeking comments on these proposed updates. FinCEN’s newfound ability to analyze the data it has seems to have allowed it to shift from a two-hours-for-all-SARs approach to a much more nuanced, data-driven approach.

ADDRESSES: Comments may be submitted by any of the following methods:

- Federal E-rulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov. Follow the instructions for submitting comments. Refer to Docket Number FINCEN-2020-0004 and the specific Office of Management and Budget (OMB) control numbers 1506-0001, 1506-0006, 1506-0015, 1506-0019, 1506-0029, 1506-0061, and 1506-0065.

- Mail: Policy Division, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, P.O. Box 39, Vienna, VA 22183. Refer to Docket Number FINCEN-2020-0004 and OMB control numbers 1506-0001, 1506-0006, 1506-0015, 1506-0019, 1506-0029, 1506-0061, and 1506-0065.

Please submit comments by one method only. Comments will also be incorporated into FinCEN’s review of existing regulations, as provided by Treasury’s 2011 Plan for Retrospective Analysis of Existing Rules. All comments submitted in response to this notice will become a matter of public record. Therefore, you should submit only information that you wish to make publicly available.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: The FinCEN Regulatory Support Section at 1-800-767-2825 or electronically at frc@fincen.gov.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

I. Statutory and Regulatory Provisions

The legislative framework generally referred to as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) consists of the Currency and Financial Transactions Reporting Act of 1970, as amended by the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001 (USA PATRIOT Act) (Public Law 107– 56) and other legislation. The BSA is codified at 12 U.S.C. 1829b, 12 U.S.C. 1951–1959, 31 U.S.C. 5311–5314 and 5316–5332, and notes thereto, with implementing regulations at 31 CFR Chapter X.

The BSA authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury, inter alia, to require financial institutions to keep records and file reports that are determined to have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, and regulatory matters, or in the conduct of intelligence or counter-intelligence activities, to protect against international terrorism, and to implement counter-money laundering programs and compliance procedures.[1] Regulations implementing Title II of the BSA appear at 31 CFR Chapter X. The authority of the Secretary to administer the BSA has been delegated to the Director of FinCEN.[2] Under 31 U.S.C. 5318(g), the Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to require financial institutions to report any suspicious transaction relevant to a possible violation of law or regulation. Regulations implementing 31 U.S.C. 5318(g) are found at 31 CFR 1020.320, 1021.320, 1022.320, 1023.320, 1024.320, 1025.320, 1026.320, 1029.320, and 1030.320. The information collected under these requirements are made available to appropriate agencies and organizations as disclosed in FinCEN’s Privacy Act System of Records Notice relating to BSA Reports.[3]

II. Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA)[4]

Title: Reports by Financial Institutions of Suspicious Transactions (31 CFR 1020.320, 1021.320, 1022.320, 1023.320, 1024.320, 1025.320, 1026.320, and 1029.320). OMB Control Numbers: 1506-0001, 1506-0006, 1506-0015, 1506-0019, 1506-0029, 1506-0061, and 1506-0065.[5]

Report Number: FinCEN Report 111 – Suspicious Activity Report (SAR).

Abstract: FinCEN is issuing this notice to renew the OMB control numbers for the SAR regulations and the SAR report.

Type of Review: Renewal without change of currently approved information collections.

Affected Public: Businesses or other for-profit institutions, and non-profit institutions.

SAR Regulations

Estimated Burden: An administrative burden of one hour is assigned to each of the SAR regulation OMB control numbers in order to maintain the requirements in force.[6]

JRR Comment: One hour is the current “administrative burden” of preparing and filing a SAR.

The reporting and recordkeeping burden is reflected in FinCEN Report 111 – SAR, under OMB control number 1506-0065. The rationale for assigning one burden hour to each of the SAR regulation OMB control numbers is that the annual burden hours would be double counted if FinCEN estimated burden in the industry SAR regulation OMB control numbers and in the FinCEN Report 111 – SAR OMB control number.

FinCEN Report 111 – SAR

Type of Review:

- Propose for review and comment a re-calculation of the portion of the PRA burden that has been subject to notice and comment in the past (the “traditional annual PRA burden”).

- Propose for review and comment a method to estimate the portion of the PRA burden that FinCEN previously had not included (the “supplemental annual PRA burden”).

JRR Comment: FinCEN is acknowledging that its current burden estimate (i) needs to be re-calculated, and (ii) needs to be augmented. And it now has the means to do so through its BSA Value Project.

Frequency: As required.

Estimated Number of Respondents: 12,148 financial institutions.[7]

JRR Comment: The estimated number of respondents – 12,148 financial institutions – and the accompanying footnote is the first interesting nugget of information. The footnote includes the phrase “not all financial institutions identify suspicious activity that would warrant a SAR filing”. This is a benign phrase, hidden in a footnote, that could be the headline of a GAO report: arguably, every regulated financial institution, no matter how small, should identify and report at least one suspicious transaction in any given year. See my comments below Table 1.

Estimated Reporting and Recordkeeping Burden:

In this notice, FinCEN introduces two substantial modifications to the scope and the methodology we previously used to estimate the annual PRA burden associated with the SAR. First, with respect to the scope of the estimate, FinCEN’s traditional annual PRA burden estimate associated with the SAR included only the filer’s annual operational burden and cost associated with (a) producing and filing the report, and (b) storing a copy of the filed report. Starting with this notice, FinCEN intends to add a supplemental annual PRA burden estimate that reflects the annual costs involved in (a) determining whether alerts that were elevated for further review merit filing a SAR, and (b) documenting the decision not to file a SAR when a case does not merit it.[8]

JRR Comment: This is where FinCEN explains what it is proposing to do. FinCEN recognizes that there is a complex process to monitor for and alert on unusual activity, determine whether to investigate that activity, to investigate that activity and, if it is suspicious to prepare and file a SAR or if not suspicious to document why it is not suspicious. Later, FinCEN describes these as the six stages in the SAR filing process. In Footnote 8, though, FinCEN acknowledges that it “lacks the granular data to estimate the costs of certain steps in that process”. In fact, it lacks the data to include the burdens for steps 1-3, which arguably may be the most burdensome from both time and cost perspectives.

Second, with respect to the methodology underlying the PRA burden and cost estimates, rather than continuing to allocate a single PRA burden and cost to the completion, submission, and storage of any type of SAR, FinCEN proposes to estimate the individual PRA burden and cost of different categories of SARs, grouped by the SARs’ estimated degree of complexity. Because there is no direct way to measure the complexity and related effort and cost of producing each SAR, FinCEN uses key features of SARs filed in 2019 to categorize them based on similar combinations of those key features, under the assumption that such combinations of key features reflect similar levels of effort and cost necessary to produce the SARs.

JRR Comment: This is where FinCEN is acknowledging that not all SARs are the same. Later, FinCEN identifies five types of SARs for its burden estimates, differentiated by (i) whether they are original SARs or “continuing activity” SARs; (ii) whether filed by banks and credit unions (collectively, “depository institutions” or “DIs”) or all other types of filers (“Non-DIs”); (iii) whether they are “standard” complexity or “extended” complexity; and (iv) whether they were batch-filed or filed as a discrete, stand-alone SAR.

Part 1 below sets out the breakdown of the SARs filed during 2019 according to the key features that are used to group SARs into categories subject to similar PRA burden and cost. Part 1 also contains the analysis of how some combinations of key features worked or failed to work as proxies for a SAR’s complexity and, therefore, burden and cost.

Part 2 uses the results of the analysis in Part 1 to estimate the individual and total annual PRA burden and cost of each category of SARs. The methodology described in Part 2 covers both the traditional and the supplemental annual PRA burden estimate.

Part 1. Breakdown of the 2019 SAR Filings

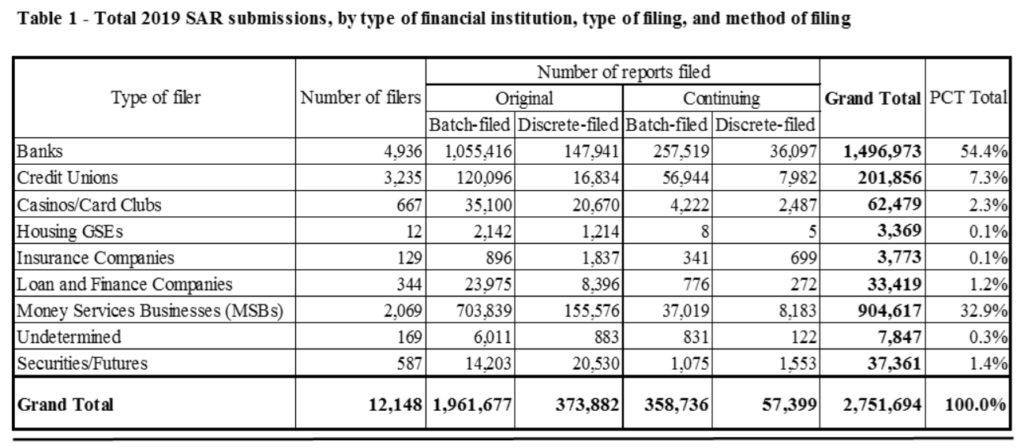

In 2019, 12,148 financial institutions (the “filing population”) submitted 2,751,694 SARs (the 2019 SAR submissions).[9] The distribution of the 2019 SAR submissions, by type of filing (original or continuing),[10] type of financial institution,[11] number of reports per filer per year, and method of filing (batch or discrete),[12] is presented in Table 1 below:

Table 1 shows that banks submitted slightly over half of the total number of SARs filed in 2019. Money services businesses (MSBs) and credit unions contributed 32.9% and 7.3% of the total, respectively. Approximately 85% of the filings from all financial institutions consisted of original reports. In addition, approximately 85% of the reports were batch filed.

JRR Comment: The most interesting aspect of Table 1 is not what is included in the Table – which is the number of financial institutions, by type, that filed SARs in 2019, but what is not included in the Table – the total number of financial institutions, by type.

- Banks – FDIC data shows that there were 5,186 banks at the end of 2019. So 95% of banks filed at least one SAR in 2019, which means that 5% or 250 banks didn’t file a single SAR in 2019.

- Credit Unions – NCUA data shows that there were 5,236 credit unions at the end of 2019. Using this data, 62% of credit unions filed at least one SAR in 2019, which means that 38% or 2,001 credit unions didn’t file a single SAR in 2019.

- Securities/Futures – In this “catch all” category, FinCEN’s May 11, 2016 Final Rule for CDD/Beneficial Ownership provided that there were 16,404 entities in this class. SEC data suggests ~3,800 registered entities. At best, 15% of the regulated financial institutions in the Securities/Futures class are filing SARs.

- Money Services Businesses (MSBs) – There are 22,736 MSBs registered with FinCEN. So less than 10% of registered MSBs filed at least one SAR in 2019.

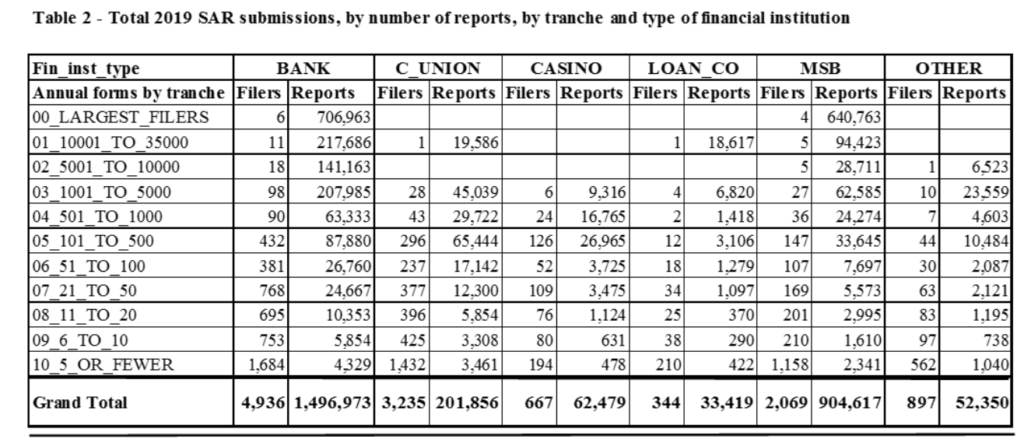

To determine the concentration of 2019 SAR submissions among the filing population, FinCEN grouped filers in tranches according to the number of SARs filed during the year. Table 2 sets out the number of reports per tranche,[13] and Table 3 sets out (i) each tranche as a percentage of the total filer population, and (ii) each tranche’s reports as a percentage of the 2019 SAR submissions.[14]

JRR Comment: It is useful to group filers according to the number of SARs filed. But what would be more useful is to group them by size of institution. The problem, though, is determining what “size” is across diverse institution types. Total deposits might be the best proxy for banks and credit unions (better than total assets, which can be located outside the United States and aren’t tied to transactions as much as deposits are), but that measure doesn’t work for MSBs or Casinos.

However, 95% of SARs are filed by Depository Institutions (62%) and MSBs (33%). I would propose that Depository Institutions be grouped by tranches of Total Deposits, and MSBs be grouped by number of domestic agent locations.

Ten filers (six banks and four MSBs) made up the first tranche (00_LARGEST FILERS). As set out in Table 3, these ten filers accounted for nearly half of the 2019 SAR submissions. Slightly less than 2% of the filing population (Tranches 00 to 03) submitted 81% of all the reports. Additionally, out of the filing population, 81% contributed slightly less than 4% of the filings, while 56% submitted fewer than 10 reports per year.

JRR Comment: These two tables are critical. First, though, is some much-needed context for banks and credit unions. Of the 5,236 credit unions, only 10 have assets greater than $10 billion, and the largest is $90 billion. 90% of credit unions have less than $565 million in assets. Of the 5,186 banks, 143 have assets of more than $10 billion, 32 are larger than $90 billion, and the 4 largest are all over $1.5 trillion in assets. But most banks, like credit unions, are very small: 75% of banks have less than $565 million in assets.

Looking at 50 or fewer SARs filed per year – or less than one per week – shows that 80% of banks and 81% of credit unions that filed SARs in 2019 filed fewer than 1 per week on average. And almost 60% of each filed fewer than 10 in the entire year.

The ten largest SAR filers – six banks and four Money Services Businesses – filed more than 540 SARs every business day, on average! The top 2% of banks and credit unions filed more than 80% of the SARs.

Question – is it time for a bifurcated regulatory approach, similar to the CCAR/DFAST approach taken for capital and liquidity purposes?

JRR Comment: The main flaw in the approach of grouping institutions by the number of SARs filed is that you could have a $100 million asset (deposits) institution, or a 10-agent MSB appropriately filing 50 SARs a year, and a $100 billion asset institution or a 100-agent MSB inappropriately filing 50 SARs a year, yet they are included in the same tranche.

Unlike currency transaction reports, for example, which are more easily categorized because they are filed based on objective criteria (i.e., transaction type and threshold), each SAR may require a widely disparate level of effort depending largely on the amount of research and subjective analysis required to determine: (a) whether to file a report; (b) how to attribute the suspicious behavior to money laundering, financing of terrorism, or fraud typologies; (c) who the main persons involved in the activity are; and (d) how to explain in concise terms the rationale that led the filer to decide to file a SAR.

As FinCEN has no direct way to gauge the amount of work involved in the production of each SAR, FinCEN broke down the 2019 SAR submissions by additional key features, so that, individually or in combination, these additional key features could serve as a proxy to group SARs with similar levels of estimated complexity, and therefore, with similar estimated PRA burden. The additional key features in the SARs that FinCEN has concentrated its analysis on are: (a) the number of persons identified as subjects; (b) the number of distinct suspicious activities selected;[15] (c) the length of the narrative section; and (d) whether or not the report contains an attachment.[16]

JRR Comment: One can debate whether these are the best proxies for complexity, but this is a tremendous first step in determining relative complexity and estimated PRA burden.

- Number of Subjects/Suspects – this is a good proxy. As a general rule, the more suspects, the more complex the underlying activity.

- Number of distinct suspicious activities selected – Footnote 15 indicates that the SAR has 18 categories of suspicious activities. I’m not sure where that number comes from. There are 11 categories of suspicious activity, each with 1 or more sub-types of activity (a total of 79 sub-types plus “other” for each category). There are also 10 instrument types and 21 product types. I recommend that FinCEN use some AI/Machine Learning techniques to analyze the combinations of suspicious activity types, instruments, and products. FinCEN attempted this in its “tractable segmentation” approach, below.

- Length of narrative – FinCEN recognizes some of the shortcomings of this attribute, and adjusts for it, but this is a good first step.

- Attachment – FinCEN recognizes the shortcomings, adjusts for it … and it is a good first step.

I didn’t see anything about the amount being reported (with more reported activity indicating more complexity), or the period of time between the first reported activity and the last reported activity (the greater the period of activity indicating more complexity), or the period of time between the first reported activity and the date of the SAR (which could indicate a lookback or review).

Once FinCEN identifies the combination of key features that are common to the largest number of reports submitted by a given type of filer (the “standard content” for that type of filer), FinCEN may take such combination as a proxy for the content and estimated complexity of a “standard” SAR for that filer type. Reports submitted by filers of the same type that contain different features (more subjects, more suspicious activities, a longer narrative) may represent SARs with “extended content” that are more complex, and therefore carry a larger PRA burden and cost for that filer type. Based on the data available, FinCEN is considering only two levels of SAR complexity.

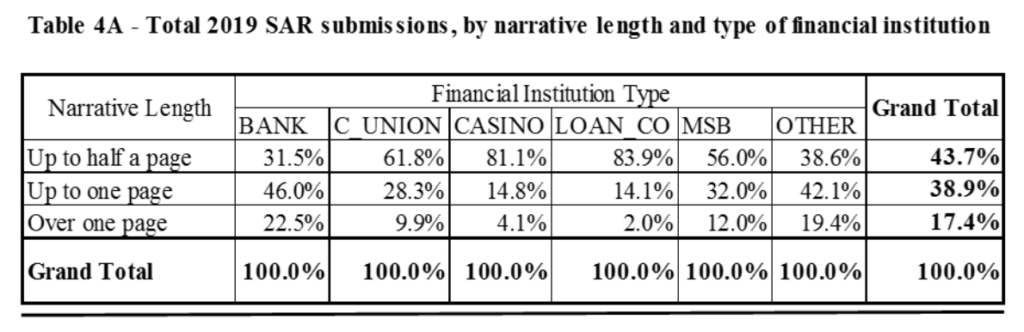

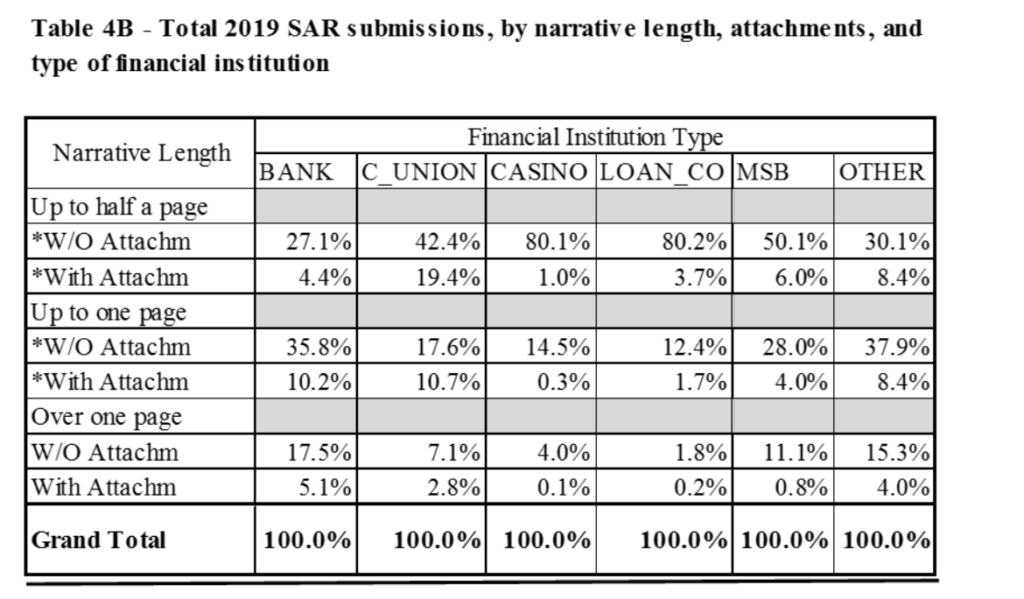

Table 4A shows a breakdown of the 2019 SAR submissions by type of financial institution and narrative length. Table 4B shows the percentage of reports with and without attachments, by type of financial institution, and narrative length.

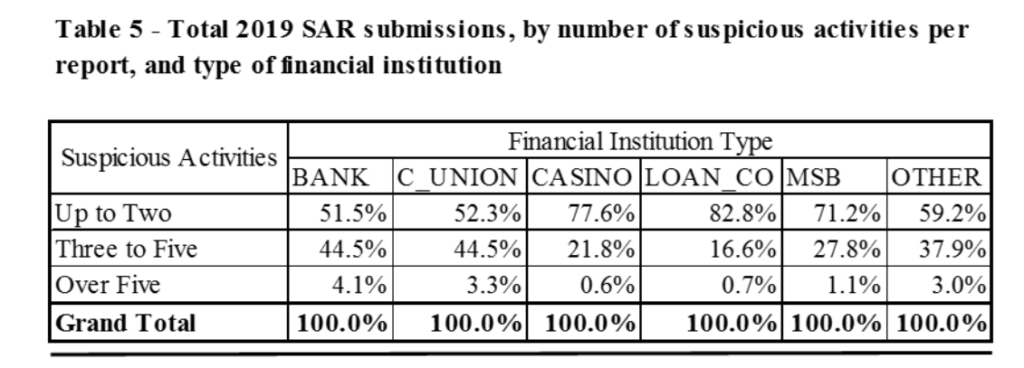

Table 5 breaks down the 2019 SAR submissions by type of financial institution and number of suspicious activities identified in each report.[17]

JRR Comment: The differences in the number of selected suspicious activities can be caused by differences in style, practices, or training from one institution to another. For example, one filer may consider a check fraud involving an elderly customer to be one category (check fraud), another two categories (check fraud, Elder Financial Exploitation), another six categories (check fraud, identity theft, providing questionable or false documentation, Elder Financial Exploitation, forgeries, identity theft).

I would combine the “tranche and type” data from Tables 2 and 3 with the number of suspicious activity categories from Table 5: the data may show that the fewer SARs an institution files, the fewer suspicious activity categories there are.

Approximately 44% of the SARs submitted by all filers have narratives not exceeding 2,000 characters (half a page), and another 39% have narratives above half a page but not exceeding one page. Most SARs (60%) identify up to two suspicious activities, while another 38% list between three and five.

FinCEN analyzed key features of the 2019 SAR submissions described in Tables 1 through 5 to generate a tractable segmentation of the SAR universe into different levels of burden. FinCEN based this segmentation on the following observations:

- FinCEN was not able to limit the criteria for selecting categories of SAR burden to the type of financial institution or the tranche of a filer alone because of large variations in the combination of features within each type of financial institution or tranche. It was possible, however, to arrive at a small number of complexity categories by combining key features that highlight significant differences between depository institution filers (banks and credit unions), MSBs, and other types of financial institution filers (non-depository institutions).

- Based on the analyzed complexity features as well as FinCEN’s extensive use of SARs in its work, in general and on average,[18] the content of SARs shows the following general features:

- There appears to be a positive correlation between the number and complexity of a financial institution’s main business lines, and the value registered by some of the key features selected: the higher the number and complexity of the filer’s business lines, the higher the number of suspicious transactions identified and the longer the narrative.

- In general, non-depository institutions with a single primary business line (i.e., loan and finance companies or casinos) file reports that (a) list up to two suspicious transactions involving one subject and a single transaction or a small number of transactions over a short period of time, and (b) use relatively short narratives of up to half a page to explain the basis for their suspicion.

- Some SARs filed by non-depository institutions have features indicating complexity, particularly longer narratives, despite the SARs not being complex. A sample of the SARs filed by two of the largest non-depository institutions showed that in 94% of the SARs with longer narratives, the increased length was due to listing transactions the filer appeared to have tracked automatically. Six percent of those SARs appeared to have required greater analytical effort. To estimate the number of SARs with extended content filed by non-depository institutions in 2019, FinCEN therefore applied the six percent threshold to the total number of SARs with narratives over one page filed by non-depository institutions.

- Nearly three quarters of original SARs filed by depository institutions report only up to two subjects involved in up to five suspicious activities, described in a narrative that does not exceed one page, and on their face do not appear complex.

JRR Comment: This is one of the most important statements in this Notice. Essentially, FinCEN is saying that ¾ of the 2.7 million SARs filed are not complex. Can these SARs be filed without human intervention with little, if any, material loss in utility or value to law enforcement?

Many SARs filed by depository institutions, however, have features indicating complexity. This may reflect any combination of the factors laid out in the tables above – number of subjects per SAR, number of suspicious transactions listed per SAR, length of the narrative, and presence of an attachment. However, some SARs that appear complex based on these features often are not in reality. Depository institutions, which in general tend to offer many business lines mostly to established customers, sometimes include in SARs a comparison of other information they maintain. This can increase the apparent complexity of SARs analyzed against the complexity factors FinCEN identified without necessarily being indicative of a SAR requiring extensive research. FinCEN controlled for this by removing from the complex category SARs that had a high ratio of digits to non-digit text in the SAR narrative, because a high ratio of digits often indicates the algorithmic inclusion of transaction data in the SAR narrative.

JRR Comment: This was a great catch by FinCEN. And below might have been a miss by FinCEN. Whether “continuing activity” SARs require “substantially less effort”, or any less effort than original SARs, is worth exploring.

- For all financial institutions, FinCEN estimates that the review of cases documenting the need to file continuing SARs, and the filing of the continuing SARs themselves, will require substantially less effort than the review of cases leading to the filing of original SARs, and the actual filing of such original SARs.

- Lastly, FinCEN assumes that financial institutions that batch file SARs have a degree of automation they can employ to the partial filling of the report. Batch filers will also store electronic files that may contain several reports per file. Based on these assumptions, FinCEN allocates a lower PRA burden per report to these filers. This burden consists of the actual time of submission per report (which may be close to instantaneous), and the administrative and supervisory tasks involved in this stage.

As noted, reflecting the observations above, FinCEN identified five categories of SARs to generate a tractable segmentation of complexity for analyzing estimated PRA burden: (a) continuing SARs; (b) original SARs with standard content filed by nondepository institutions; (c) original SARs with extended content filed by non-depository institutions; (d) original SARs with standard content filed by depository institutions; and (e) original SARs with extended content filed by depository institutions.

JRR Comment: This is the first of three steps FinCEN takes in estimating the SAR burden – identifying the five categories of SARs. The second and third steps follow: identifying the six stages in the SAR filing process, and the four types of people involved in that process, respectively.

Part 2. PRA Burden and Cost Estimates

Based on industry input, including input obtained over the past year in a project assessing how to improve the effectiveness of BSA data and measure its value for each stakeholder group, FinCEN understands that the SAR filing process comes at the end of a larger process that varies in complexity depending on the type and size of the financial institution:[19]

JRR Comment: On the following page is FinCEN’s six-stage SAR production process. This is a good first step, but I disagree with the approach that, for purposes of the PRA burden and cost estimates, the SAR process is distinct from the overall BSA/AML program process (and burden and cost). The singular purpose of the BSA/AML program regime is to provide timely, actionable intelligence to law enforcement and the intelligence community by way of BSA reports and recordkeeping – primarily SARs and CTRs. Therefore, integral to the SAR production process are the program requirements of risk assessment, CIP/CDD, training, independent testing, examination management, etc. These costs will be included in future notices.

Stage 1 – Maintaining a Monitoring System: Commensurate with the size of the filer and the complexity of its operations, each filer will run, update, and upgrade a monitoring system that reflects its assessment of risk. This monitoring system will vary in complexity from a manual review process to a fully automated one.[20]

JRR Comment: The use of the singular “monitoring system” minimizes the complexity of even the smallest institution’s program to have employees escalate unusual activity (referrals), to have manual or automated monitoring systems identify unusual activity (alerts), and the regulatory and operational requirements to run, update, and upgrade those systems. Larger, more complex institutions will run dozens of monitoring and surveillance systems.

Stage 2 – Reviewing Alerts: When the monitoring system issues an alert, the filer will have to determine whether the alert reveals a true potential risk event, or is a false positive.

JRR Comment: As FinCEN explains below, it is not including this stage in its burden and cost estimate “due to the lack of the necessary granular information”. Transaction monitoring and customer surveillance systems, and the alerts that are generated, are a major part of the burden and cost of AML programs. The issue of high false positive rates – anecdotally 95 percent or more of alerts are so-called “false positives” – is often-discussed, always-lamented, and remains an intractable problem. See: https://regtechconsulting.net/uncategorized/rules-based-monitoring-alert-to-sar-ratios-and-false-positive-rates-are-we-having-the-right-conversations/. Also see: https://regtechconsulting.net/uncategorized/flipping-the-three-aml-ratios-with-machine-learning-and-artificial-intelligence-why-bartenders-and-aml-analysts-will-survive-the-ai-apocalypse/

Stage 3 – Transforming Alerts into Cases: If, based on the filer’s analysis, the alert points to a true potential risk event, the filer will gather additional information to present the case to the reviewing level that will eventually decide whether the event merits the filing of a SAR.

JRR Comment: FinCEN has done a good job recognizing that many institutions have an alert review or alert triage process to determine if an alert should “go to case” or not. But like stages 1 and 2, this third stage is not included in the burden and cost analysis at this time.

Stage 4 – Case Review: The appropriate level will review the case to determine whether or not the event constitutes a suspicious activity that must be reported.

Stage 5 – Documentation of Determination: This notice takes into account that filers document decisions they make as part of Stage 4 that lead them to conclude that an event does not warrant the filing of a SAR.

Stage 6 – SAR Filing Process: If an event warrants the filing of a SAR, the filer will follow its SAR filing process, including: (a) selecting supporting documentation; (b) completing the report, including drafting the narrative; (c) filing the report through batch or discrete filing; and (d) storing the filed report and supporting documentation in physical or electronic form.

Each stage requires the filer’s use of human and technological resources, which combination will vary according to the sophistication of the filer. Previously, FinCEN limited its annual SAR PRA burden estimate to Stage 6 mentioned above, the SAR filing process (the “traditional annual PRA burden”). In this notice, FinCEN expands its PRA burden estimate to include Stages 4 and 5 listed above (the “supplemental annual PRA burden”).

JRR Comment: Stages 4 and 5 are the “supplemental annual PRA burden” that FinCEN is adding. Until now, FinCEN only included Stage 6 in its PRA estimate. Now FinCEN is considering Stages 4, 5, and 6.

FinCEN is not addressing the burden associated with Stages 1 to 3 above due to the lack of the necessary granular information. Notably, FinCEN would need information regarding: (i) the levels of burden and cost attributed to differing monitoring systems; (ii) varying levels of complexity in determining whether alerts represent true alerts; and (iii) the amount of research involved in assembling cases to determine whether true alerts warrant the filing of a SAR. Furthermore, FinCEN would need additional information to identify the proportion of these costs that are strictly connected to the filing of a SAR relative to the same costs associated with a filer’s other regulatory or business requirements. FinCEN intends to address the information required for the estimate of the burden and cost of Stages 1 to 3 in a future notice. FinCEN acknowledges that each stage of the SAR production contributes to the next (including those stages of the process not included in this notice). FinCEN assesses, however, that the information provided by this notice, though not a complete estimate of the SAR PRA burden, improves the estimate and creates a foundation for a future estimate of the costs of all six stages.

JRR Comment: It is incumbent on the industry to provide FinCEN with data and information on Stages 1, 2, and 3 of the process, as well as on the other aspects of a program that are not reflected in these six stages: the program requirements of risk assessment, CIP/CDD, training, independent testing, examination management, etc., that are integral to, and part of, the SAR production and filing process.

FinCEN recognizes that SAR cases that are more complex may take a longer time to review at multiple stages, such as the case investigation point in Stage 4 and the SAR filing point in Stage 6. However, for ease of presentation, FinCEN calculated the extra burden of handling complex cases in our burden estimate for Stage 6, and attributed a burden that represents our estimate of the standard administrative work connected to continuing and original SARs to Stages 4 and 5. Therefore, the total estimate proposed in this notice will be the aggregate of the following estimates of the PRA burden related to:

- Evaluating cases for potential SAR filing (Stage 4). This will be part of the supplemental annual PRA burden calculation.

- Recordkeeping of cases not converted into SARs (Stage 5). This will be part of the supplemental annual PRA burden calculation.

- The SAR filing process (Stage 6). This will be part of the traditional annual PRA burden calculation and will include the PRA burden associated with the filing of (i) continuing SARs, (ii) original SARs filed by non-depository financial institutions, and (iii) original SARs filed by depository financial institutions.

JRR Comment: Up to this point, FinCEN has introduced the first two of the three components of its PRA burden and cost estimate: the five categories of SARs, and the six stages of the SAR filing process. Now FinCEN turns to the third component: the people involved in the process. FinCEN has identified four.

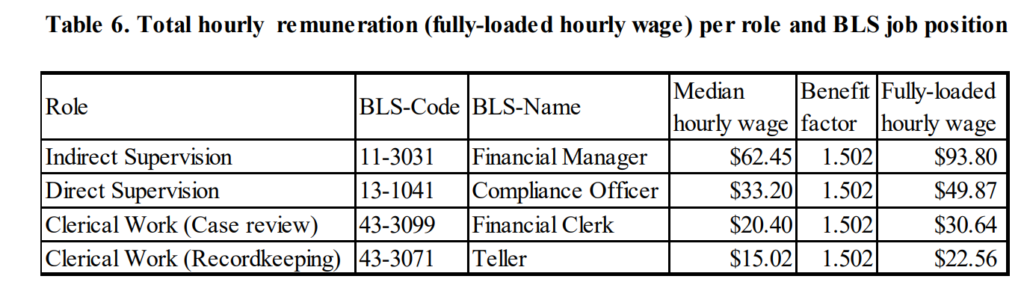

FinCEN identified four staff positions and corresponding roles involved in the SAR process in order to estimate the hourly costs associated with the burden hour estimates calculated in this part. Those are: (i) general supervision (providing process oversight); (ii) direct supervision (reviewing operational-level work and cross-checking all or a sample of the filings against their supporting documentation); (iii) clerical work (engaging in case evaluation to support the determination of whether a SAR must be filed); and (iv) clerical work (engaging in producing, filing, and storing SARs and supporting documentation).

JRR Comment: This is where the private sector should provide detailed comments. It has not been my experience that fraud investigators and AML analysts are performing “clerical work”, classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as “Financial Clerks” with a mean (average) hourly wage of $20.40. Based on that same data, the mean annual wage is $43,500, with a broad range across the US of $25,980 to $60,600. The same job code for the financial services NAICS (522000) shows an annual mean salary of $44,500 and a 90th percentile salary of $62,330 (10% of the people in that category make more than $62,330). Data from the private sector will (I believe) show that the annual average salary for financial crimes investigators and analysts will be more than $62,330.

FinCEN calculated the fully loaded hourly wage for each of these four roles by taking the median wage as estimated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and computing an additional benefits cost as follows:[21]

JRR Comment: Financial institutions must provide comments (supported by data and information) to FinCEN on these four roles and the range and median salaries for those roles. For example, the BLS data shows that the average salary for the Compliance Officer position is $66,236 with a broad range of $39,790 to $111,640. Data should show that most compliance officers earn in excess of $100,000. And differentiating between Depository Institutions, Securities/Futures, and Non-DIs will be critical.

FinCEN estimates that, in general and on average, each role would spend different amounts of time on each stage of the process covered by this notice, as described in the specific estimates below.

1. Estimate of the burden and cost of evaluating cases for potential SAR filing

To estimate the PRA burden involved in evaluating each case generated by one or more alerts, FinCEN starts with the number of cases that, after review, resulted in the filing of 2,751,694 SARs in 2019. As set out in Table 1 above, of that total number of filings, 2,335,559 reports were original SARs, and 416,135 were continuing SARs.

JRR Comment: This may not be an accurate assumption. Again, the private sector needs to provide comments (supported by data) on the burdens and costs of filing continuing activity SARs.

In the case of continuing SARs, FinCEN assumes that the filer will be monitoring the specific transactions of the previously identified subject, and filing a continuing SAR every ninety days (if the subject did not discontinue the activity), and noting the cumulative monetary amount involved in the suspicious activity. FinCEN therefore assesses that the number of continuing suspicious activity cases will equal the number of continuing SARs.

In the case of original SARs, however, a filer may need to review a large number of cases to determine which cases justify the filing of a report. A paper issued by the Bank Policy Institute in 2018 (the “BPI Paper”)[22] contains the estimates of 13 large, midsize, and small banks (with assets under management of more than $500 billion, between $200 to $500 billion, and between $50 and $200 billion, respectively) about their average conversion rate[23] of cases to SARs. The BPI Paper states that, on average, banks filed SARs on 42% of alerts turned into cases (i.e., alerts that are not considered false positives).[24] In the absence of similar data for other types of financial institutions, FinCEN adopts the bank average conversion rate from cases to SARs set out in the BPI Paper (42%) to approximate the number of cases that could have generated the number of original SARs filed in 2019. If 42% of cases result in the filing of a SAR, the total filing population would have had to review approximately 5,560,854 cases[25] to report the 2,335,559 original SARs submitted in 2019.[26]

JRR Comment: FinCEN got the case-to-SAR conversion rate of 42 percent from the BPI paper. FinCEN refers to pages 5-7 of the BPI paper. Notably, the BPI survey respondents were 19 banks that all had assets of $50 billion or more: there are only 43 such banks. These 19 banks were grouped into small ($50 – $200 billion, at which time there were 33 such banks in total), midsize ($200 – $500 billion in assets, at which time there were 6 such banks in total), and large (greater than $500 billion, at which the time there were 4 such banks). Thirteen (13) of the 19 banks provided data on Alert-to-Case-to-SAR numbers:

- Large Banks – generated 2.8 million alerts of which 20% (560,000) became cases, of which 42% (235,200) became SARs;

- Midsize banks – generated 117,000 alerts of which 9.5% (11,115) became cases, of which 54% (6,002) became SARs;

- Small banks – generated 107,000 alerts of which 8% (8,560) because cases, of which 53% (4,537) became SARs.

Combined, the three tranches of banks generated 3,024,000 alerts which resulted in 579,675 cases, which eventually became 245,739 SARs. This overall Case-to-SAR conversion rate was 42%.

FinCEN estimates that the average burden involved in considering whether a case merits filing an original SAR, for all types of financial institutions and for any type of suspicious transactions, would be 20 minutes per case. FinCEN estimates that the average burden involved in reviewing cases involving continuing SARs will be much lower, at 3 minutes per case.

JRR Comment: These two assumptions – 20 minutes to determine whether a case merits filing an original SAR, and 3 minutes to determine whether continuing activity merits filing a continuing activity SAR – should be tested by financial institutions’ comments to FinCEN. These are important assumptions which may not prove true.

FinCEN assumes that the review of cases will involve the participation of three of the roles described above, as follows:[27]

Table 7

JRR Comment: Once a case is opened, the common practice is to assign it to a fraud investigator or AML analyst to determine whether the overall activity of the customer meets the definition of “suspicious activity”. If it does, the analyst will then prepare a SAR: if the analyst determines that a SAR is not warranted, they will document their decisioning and close the case. Depending on the type of case, there may be procedures for reviewing those decisions.

Financial institutions should review their data and provide comments to FinCEN: the data will likely show that 80%-90% of the total time spent determining whether a SAR is merited is on case review, 10%-20% on direct supervision, and 0%-10% on indirect supervision.

Footnote 27 below is confusing to me: in my experience, fraud investigators and AML analysts – those people that are working cases, determining whether a SAR should be filed, and preparing and filing the SAR – are not maintaining agendas, documenting minutes of meetings, or assembling files for review by SAR committees.

The total annual PRA burden of this stage involving cases related to both continuing and original SARs would be 1,874,424 hours, at a total cost of $91,846,776, as described in Tables 8A and 8B below.

Tables 8A, 8B

2. Estimate of the burden and cost of documenting cases not converted into SARs

With 2,335,559 cases resulting in SAR filings and an estimated conversion rate of 42%, out of the estimated 5,560,854 cases, 3,225,295 would be cases involving a decision not to file. FinCEN estimates that the average burden hours of documenting the rationale as to why a case does not merit filing a SAR, for all types of financial institutions and in the context of any type of suspicious transactions, would be 25 minutes per report.

JRR Comment: FinCEN is estimating that it takes 20 minutes to determine whether a SAR is merited, and an extra 5 minutes to document the reasons for not filing a SAR if a SAR is not merited. Financial institutions should provide comments, supported by data and information, on these estimates.

FinCEN assumes that documenting the rationale for not filing a SAR and the storage of the case documents will involve the participation of three of the roles described above, as follows:

Table 9

JRR Comment: In Table 7, FinCEN is estimating that the work done to determine whether a SAR is merited, and a SAR results, involves 10% indirect supervision, 60% indirect supervision, and 30% clerical work. In Table 9, FinCEN is estimating that the work done to determine whether a SAR is merited, and a SAR does not result, involves 1% indirect supervision, 19% indirect supervision, and 80% clerical work. However, with the exception of documenting no-SAR decisions, this is the same work performed by the same fraud investigators or AML analysts, supervised by the same direct supervisors. The ratios of work should be the same, or roughly the same, for both processes.

The total annual PRA burden of this stage would be 1,343,872 hours, at a total cost of $38,972,288, as described in Table 10 below:

Table 10

3. Estimate of the burden of the SAR filing process

JRR Comment: To this point, FinCEN has laid out the five categories of SARs, the six stages of the SAR filing process, and the four types of positions involved in that process. FinCEN has also described the updated or new burden and cost estimate of evaluating cases for potential SAR filing and, for those cases that result in a “no-SAR” decision, the burden and cost of documenting that decision. In this section, FinCEN turns to the burden and cost estimate of the process of preparing and filing a SAR once the decision has been made that the case merits a SAR.

But first FinCEN describes its current estimate, made ten years ago before mandatory electronic filing, before attachments were allowed, and based on the old SAR forms. That estimate, or estimates, are crude and simple: two hours for the 99% and more of SARs filed by single financial institutions, and 2.5 hours for the rare (less than 1% of the SARs) filings made jointly by two or more financial institutions.

FinCEN’s prior estimate of the traditional average burden hours associated with the SAR filing process[28] was based on a 2010 assessment of the manual effort involved in the drafting, writing, filing, and storing of a paper-based SAR with a standard narrative of 4,000 characters (i.e., one page), and the storing or segregation of paper-based supporting documentation. Since 2011, financial institutions have been able to (a) file SARs electronically either in batch or discrete format, and (b) include with their SARs an attachment containing tabular data such as transaction data providing additional suspicious activity information not suitable for inclusion in the narrative. This attachment must be an MS Excel-compatible comma separated value (CSV) file with a maximum size of 1 megabyte. These new features contribute to a substantial decrease in the hourly burden of the mechanical aspects of the filing and storage of SARs and supporting documentation.

As set out in the estimates above, the review of approximately 5,560,854 cases would result in the closing out of 3,225,295 cases, and the filing of 2,335,559 original and 416,135 continuing SARs. In the previous part, FinCEN identified a tractable segmentation of SAR complexity: (a) continuing SARs; (b) original SARs with standard content filed by non-depository institutions; (c) original SARs with extended content filed by non-depository institutions; (d) original SARs with standard content filed by depository institutions; and (e) original SARs with extended content filed by depository institutions. In all cases, the estimate represents the administrative burden involved in producing and reviewing a SAR, overseeing the process of filing a SAR, and the actual filing of a SAR, and not just the mechanical process of generating, submitting, and storing the SAR (which might be very small for fully-automated filers using the batch filing method).

FinCEN assumes that the SAR filing process involves the following four roles described in Table 6, in varying proportions depending on whether the burden accounts for the reporting or the recordkeeping stage of the process:

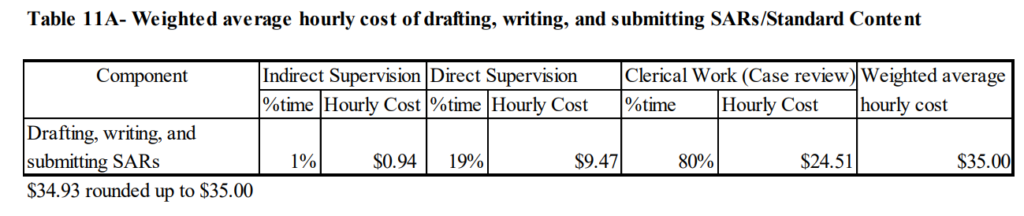

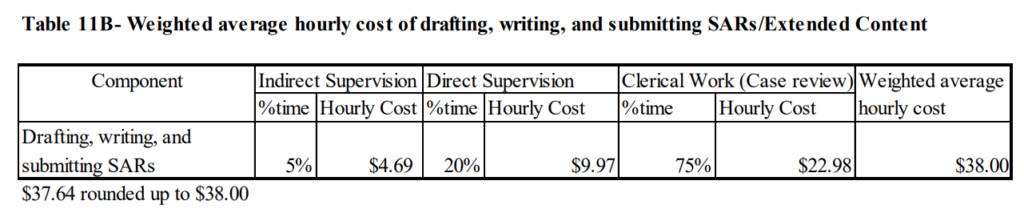

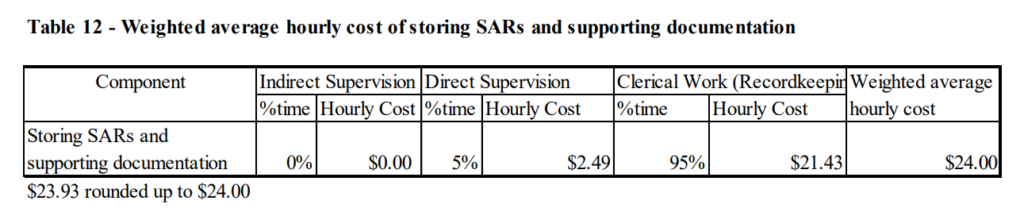

JRR Comment: Tables 11A, 11B, and 12 set out FinCEN’s estimates for the percentage of time and resulting cost that it takes, by role, for drafting, writing, and submitting “Standard Content” SARs (Table 11A); for drafting, writing, and submitting “Extended Content” or complex SARs (Table 11B); and for the recordkeeping required for both (Table 12). Where there were stark differences in the SAR/No SAR determinations, FinCEN estimates that there are only subtle differences in the ratio of time/cost for standard or simple SARs and extended or complex SARs. Financial institutions should assess their data and information and provide comments to FinCEN: my experience is that complex investigations are often handled by more experienced investigators/analysts, and not necessarily more supervision.

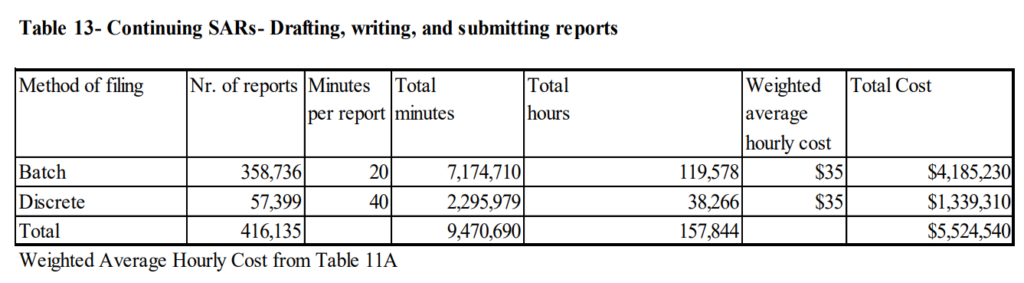

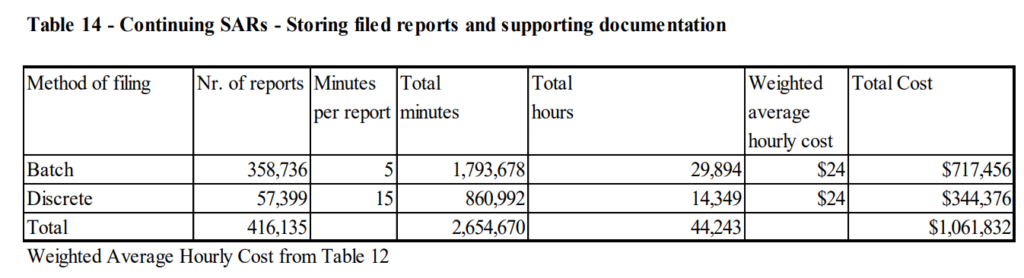

3.1. Continuing SARs

In the case of a suspicious transaction that continues over time, filers must submit continuing SARs every ninety days. Financial institutions filed 416,135 continuing SARs as part of the 2019 SAR submissions. FinCEN estimates that, on average, the burden involved in filing a continuing SAR will be relatively low, and will be substantially the same among all types of financial institutions. The estimated hourly burden and its cost for continuing SARs are as follows:

JRR Comment: FinCEN phrases these as “estimates”, but they appear to be assumptions unsupported by data rather than estimates based on data. Financial institutions should provide comments to FinCEN on the burden and costs of continuing activity SARs compared to original SARs.

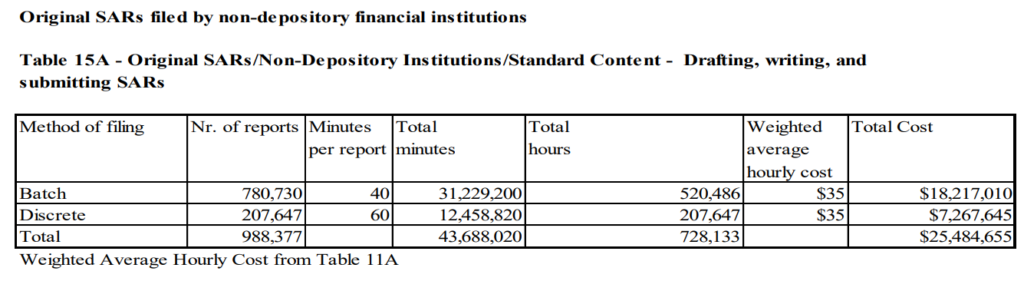

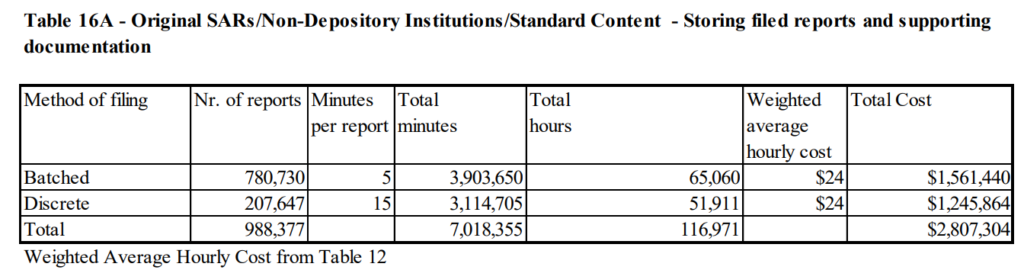

3.2. Original SARs filed by non-depository institutions

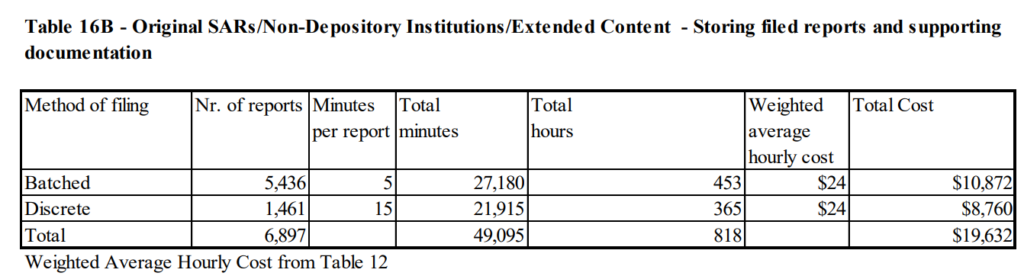

Based on the application of the percentage described in Part 1 to SARs with narratives over one page filed by non-depository institution, FinCEN identified 988,377 reports with standard content and 6,897 with extended content.

Original SARs filed by non-depository institutions (standard content)

For the purpose of calculating the burden of original SARs with standard content filed by non-depository institutions, FinCEN estimates that the average burden involved in the filing of original SARs will be higher than that of continuing SARs. Specifically, FinCEN uses an estimate of 40 minutes per batch-filed report and 60 minutes per discrete-filed report for drafting, writing, and submitting the SARs, and 5 minutes per batch-filed reports and 15 minutes per discrete-filed report for storing filed reports and supporting documentation.

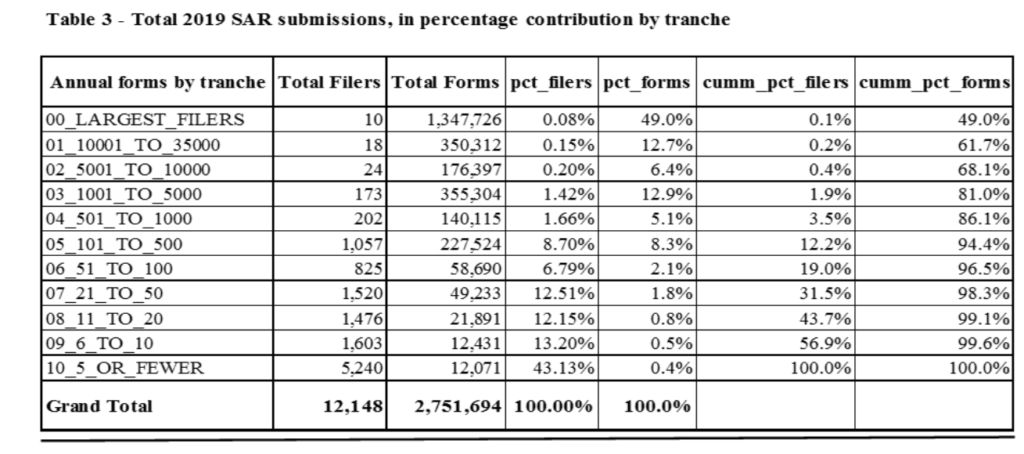

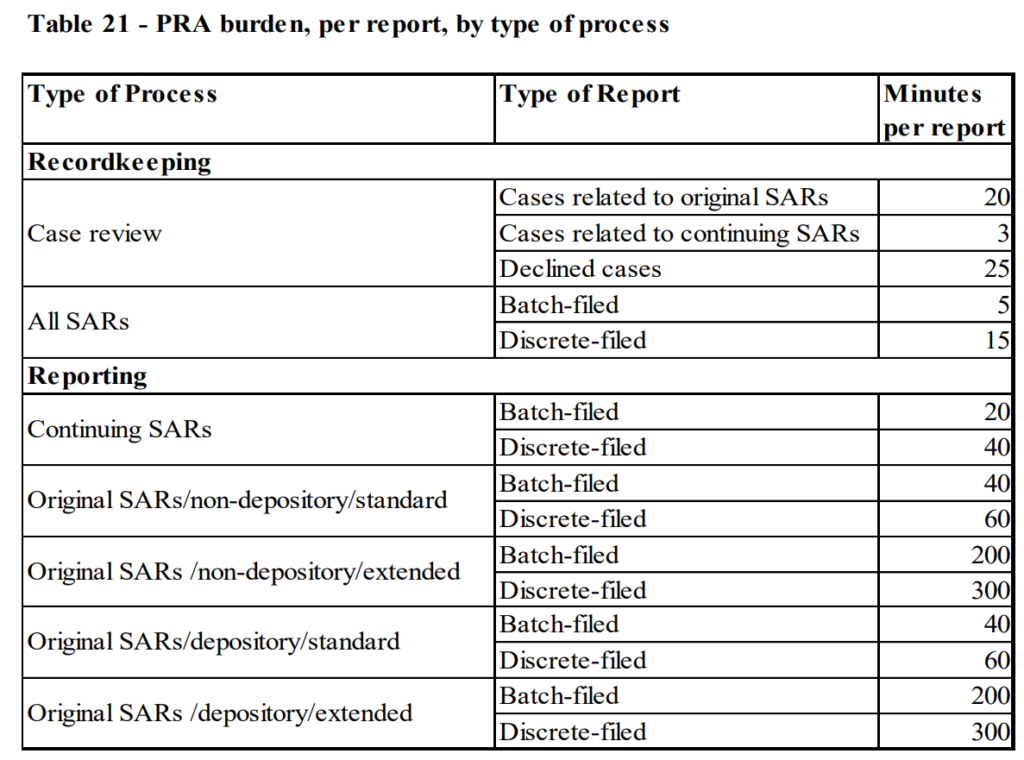

JRR Comment: FinCEN has developed a much more nuanced and granular estimate of the burden and cost of filing SARs. The old methodology was a single 120 minutes (2 hours) per SAR. With this new approach, there is a low estimate of 25 minutes for batch-filed, standard content continuing SARs, all the way to 315 minutes (more than 5 hours) for discrete-filed, extended content original SARs. All of the combinations are set out in the following sections: Depository Institution versus Non-Depository Institution; standard content versus extended content; batch-filing versus discrete-filing; and drafting, writing, and submitting SARs versus recordkeeping for SARs.

The estimated hourly burden and its cost for this subset of SARs are therefore as follows:

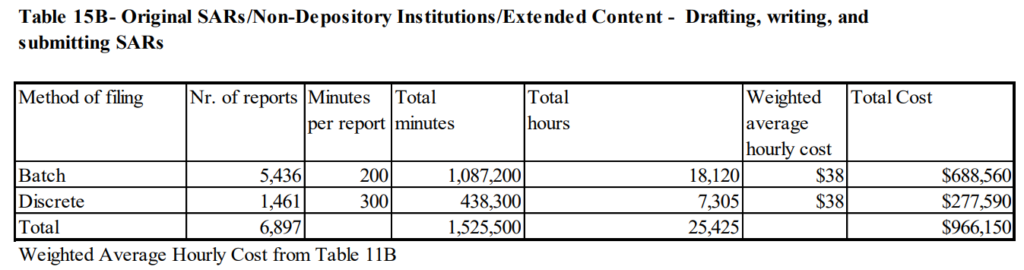

Original SARs filed by non-depository institutions (extended content)

For the purpose of calculating the burden of original SARs with extended content filed by non-depository institutions, FinCEN estimates that the average burden will be several times higher than that of standard content SARs, and the related cost will include a larger proportion of the levels of the organization with higher fully-loaded hourly wages (those representing indirect and direct supervision). The estimated hourly burden and its cost for this subset of SARs are therefore as follows:

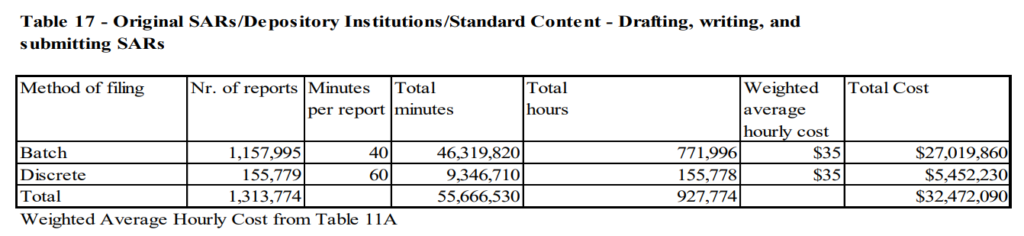

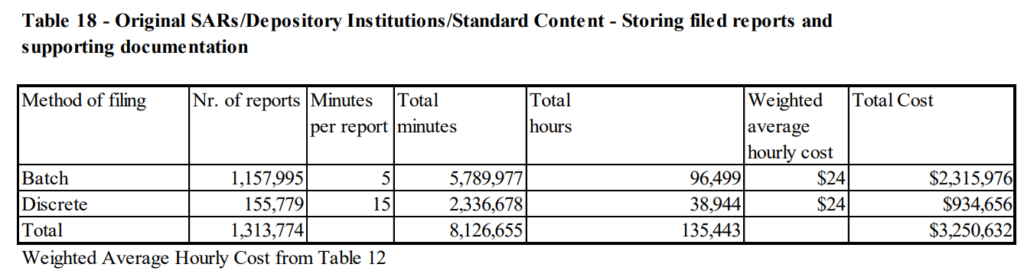

3.3. Original SARs filed by depository institutions

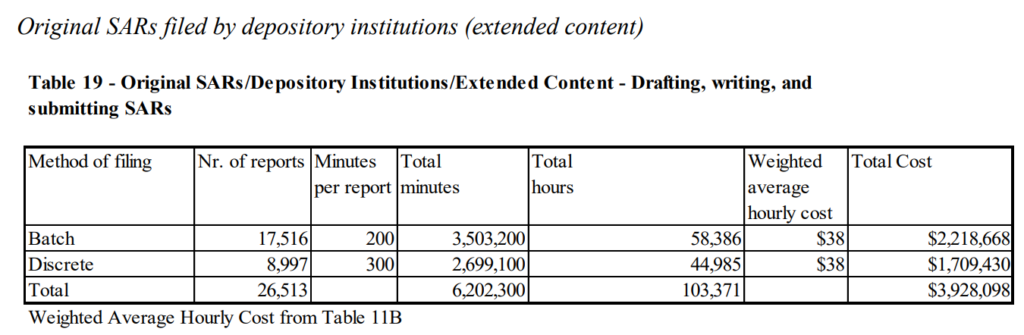

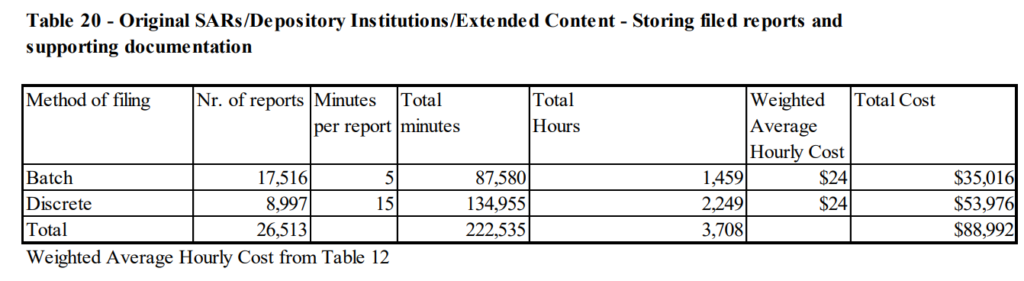

Based on the segmentation described in Part 1 of depository institution SARs into standard content and extended content, FinCEN identified 1,313,774 reports with standard content, and 26,513 that included extended content.

The estimate of the reporting and recordkeeping burden of these two SAR subsets is as follows, using the per-SAR burden estimates included in the tables:

JRR Comment: This is another significant estimate. Of the 1,340,287 original SARs filed by banks and credit unions (roughly half of all SARs filed), only 26,513 had “extended content”, which is FinCEN’s proxy for complex or, perhaps, significant SARs.

Less than 2% of the original depository institution SARs had extended content or were otherwise complex or significant SARs. The 2018 Bank Policy Institute survey of 19 large banks found that less than 4% of those SARs garnered law enforcement interest.

Estimated Reporting and Recordkeeping Burden:

The estimated reporting and recordkeeping burden by type of process and report is as follows:

JRR Comment: At the end of this document I have included a chart that visualizes the different estimated time burdens for the twelve (12) combinations of SAR filings: Original versus Continuing Activity; DI versus Non-DI; standard content versus extended content; and batch- versus discrete-filing.

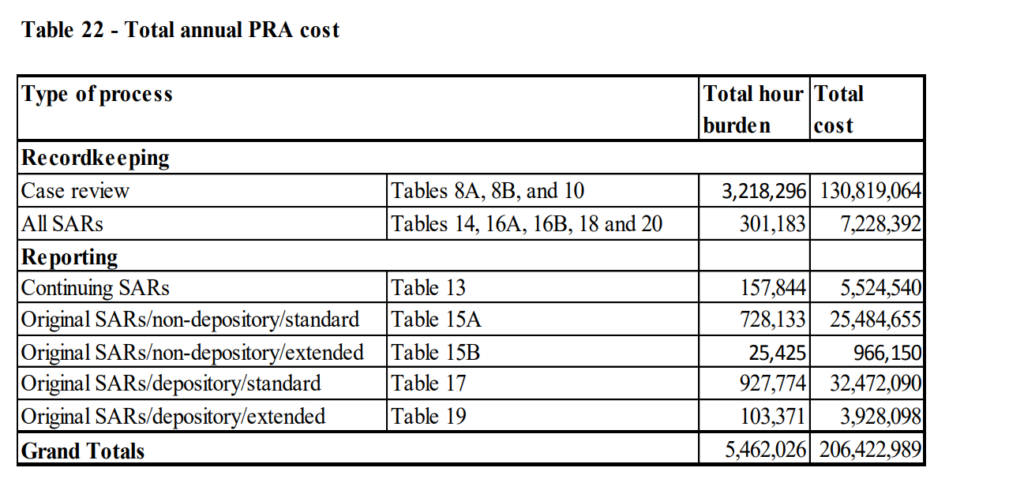

Estimated Total Annual Reporting and Recordkeeping Burden:

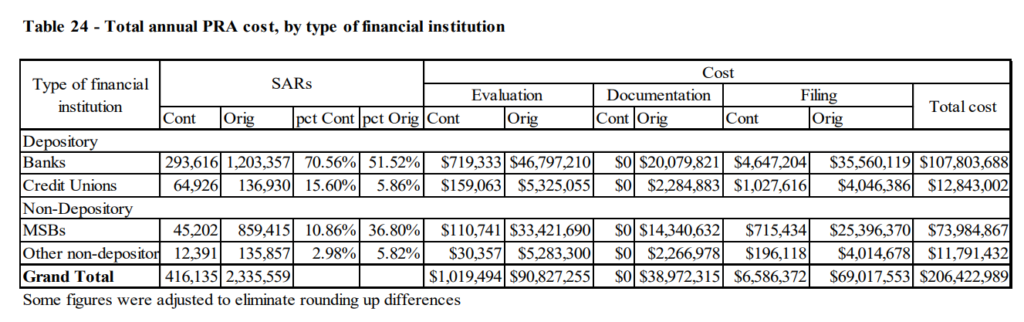

The total estimated reporting and recordkeeping burden and cost per type of process and type of report are as follows. As detailed in Table 22 below, the total estimated recordkeeping and reporting annual PRA burden for the case review and SAR filing process of the seven OMB control numbers covered by this notice is 5,462,026 hours, for a total cost of $206,422,989.

JRR Comment: FinCEN estimates that the total costs of the SAR filing process (or at least the last three of the six stages of the SAR filing process) costs $206,422,989. The Bank Policy Institute survey of 19 large banks found that 14 of those banks (that responded to the survey questions on costs) reported that they spent, on aggregate, $2,400,000,000 on AML and CFT (Countering the Financing of Terrorism) compliance. FinCEN’s estimates for 12,148 SAR filers has captured less than 10% of what 14 large banks have reported in a private survey. There is some work to be done to reconcile these numbers. FinCEN acknowledges that there is work still to be done: and I acknowledge and applaud the work that FinCEN has done to date.

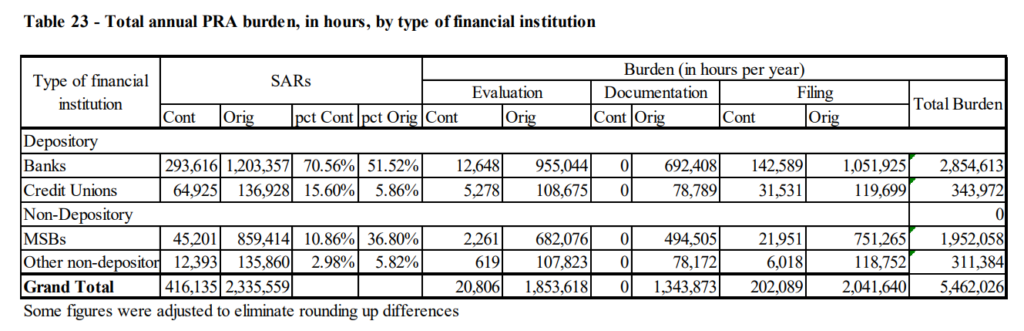

The distribution of the total estimated annual PRA burden and cost, by type of financial institution and SAR (original or continuing), and by SAR production process stage is as follows:[29]

FinCEN acknowledges that some of the partial estimates may over- or under-state the burden and cost of some the stages of the SAR production process covered by this notice, due to generalization and lack of more detailed information. FinCEN wishes to emphasize that the total burden presented in Table 22 is spread across a number of different SAR reporting requirements involving different types of financial institutions. Indeed, in the case of depository institutions, both FinCEN and the Federal banking agencies have regulations requiring SAR reporting.[30] However, only one SAR form is filed in satisfaction of the rules of both FinCEN and the Federal banking agencies. FinCEN has historically never attempted to allocate the burden between agencies for SARs required by the rules of more than one agency. FinCEN intends to conduct more granular studies of the filing population in the near future, to arrive at more realistic estimates that take into consideration a more specific breakdown of the SAR production process, including estimating the burden to financial institutions of Stages 1 to 3, which may include the inter-agency burden allocation referred to above. The data obtained in these studies may result in a significant variation of the estimated total annual PRA burden.

An agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to, a collection of information unless the collection of information displays a valid OMB control number. Records required to be retained under the BSA must be retained for five years.

Part 3. Request for Comments

JRR Comment: This is the most important part of the notice. FinCEN has six specific requests for comments, and also invites general comments. Financial institutions must take this opportunity to provide FinCEN with actual data and information: anecdotes that “the SAR regime costs too much and doesn’t produce tangible, direct benefits to financial institutions” must be replaced with data-driven information. Only then can better collective, public/private sector decisions be made.

a. Specific Requests for Comments:

Comments submitted in response to this notice will be summarized and/or included in the request for OMB approval. All comments will become a matter of public record. Comments are invited on the calculation of the total PRA burden of filing the SAR, under the current regulatory requirements. Specifically, comments are invited on the following issues:

1. FinCEN has based the estimates contained in this notice on the actual SARs filed in 2019. We have restricted the analysis to features we could measure and statements we were able to support with data extracted from the 2019 filers and submissions, using limited external data for estimates of parameters such as labor costs and conversion rates for alerts into filed SARs. FinCEN is not able to factor in its estimate of the PRA burden the burden of portions of the process for which FinCEN lacks information in filed reports or reliable existing studies. All requests for comments ask the public to suggest other factors that may affect the burden and cost of SAR reporting. Suggested factors that FinCEN could quantify by analyzing the contents of the BSA database, or by referring to statistical information publicly available, and without conducting a formal survey of the reporting financial institutions would be especially appreciated.

JRR Comment: FinCEN is looking for data and information that comes from (i) the BSA Database (accessible on FinCEN’s website) and other publicly available, reliable sources. FinCEN does not seem interested in survey-based information, such as the BPI survey that FinCEN has, in fact, relied on for this notice.

2. FinCEN proposes to expand the annual PRA burden estimate to cover three stages of the SAR production process: (a) the review of cases based on monitoring alerts considered true positives; (b) the documentation of the decision not to turn a case into a SAR; and (c) the SAR filing process. A sample conversion rate of cases that lead to SARs for depository institutions was used to calculate how many total cases at all financial institutions would have to be evaluated to produce the total number of original SARs filed in 2019. FinCEN invites comments on the characterization of these three stages, the general case conversion rate utilized, and the existence of other generally available research documents that may show different case conversion rates for different financial institution types.

JRR Comment: This is the critical issue. FinCEN is inviting financial institutions (and their trade associations and other interested parties) to provide comments, supported by data, on the first three stages of the SAR process that are not currently included in the PRA burden and cost estimate. Those three stages are: (1) maintaining a monitoring system; (2) reviewing alerts; and (3) transforming alerts into cases.

3. FinCEN estimates that, in general, the cost of labor involved in the three stages of the SAR production process covered by this notice will depend on the level of involvement in each stage of at least four different types of labor within the organization (general supervision, direct supervision, clerical work for evaluation, and clerical work for recordkeeping). Is this a reasonable identification of the roles involved in the SAR process? Has FinCEN calculated labor costs reasonably? Within the calculations of PRA burden, has FinCEN reasonably estimated the involvement of the different kinds of labor identified?

JRR Comment: FinCEN is also seeking comments on the four types of people, or positions, in the SAR filing process, their costs (salaries and benefits), and the relative time each spends on the five types of SARs across the six stages of the SAR filing process. The data in the Bureau of Labor Statistics materials, cited by FinCEN should be analyzed and compared against what FinCEN has used. See my comments above: hourly rates of $15 to $60 per hour for all participants in the SAR process appear to be materially low.

4. FinCEN arrived at estimates for (i) the hour burden of the review of all cases based on true positive alerts, and (ii) the decision not to file SARs based on the proportion of the cases that were not converted into original SARs. In general and on average, are these estimates reasonable?

JRR Comment: As indicated, this is really two issues that FinCEN is seeking comments on. One could argue that any estimate made in good faith is, in general and on average, reasonable. But I believe FinCEN is looking for something to support a higher standard than generally, on average, reasonable. It is incumbent on financial institutions to provide FinCEN with data and information to support a higher standard.

5. FinCEN segmented the universe of SAR filings into several different categories for purposes of estimating SAR complexity: (a) continuing SARs; (b) original SARs with standard content filed by non-depository institutions; (c) original SARs with extended content filed by non-depository institutions; (d) original SARs with standard content filed by depository institutions; and (e) original SARs with extended content filed by depository institutions. For each of these categories, FinCEN adjusted the estimated SAR filing burden depending on the filing method (batch or discrete). Is this segmentation reasonable? Are there other categories of SARs which FinCEN could quantify by analyzing the contents of the BSA database and without conducting a formal survey of the reporting financial institutions?

JRR Comment: Money Services Businesses (MSBs) were bucketed into the “non-depository institution” category along with the securities/futures industries’ institutions, casinos, card clubs, housing agencies, insurance companies, loan companies, and the “undetermined”. Given that 33% of all SARs were filed by MSBs, it may be better to have three categories: Depository Institutions, MSBs, and Other Non-Depository Institutions.

6. Are the other assumptions FinCEN made to calculate the burden associated with filing the different categories of SARs reasonable, such as the number of minutes required for each category of report?

b. General Request for Comments:

Comments submitted in response to this notice will be summarized and/or included in the request for OMB approval. All comments will become a matter of public record. Comments are invited on: (1) whether the collection of information is necessary for the proper performance of the functions of the agency, including whether the information shall have practical utility; (2) the accuracy of the agency’s estimate of the burden of the collection of information; (3) ways to enhance the quality, utility, and clarity of the information to be collected; (4) ways to minimize the burden of the collection of information on respondents, including through the use of automated collection techniques or other forms of information technology; and (5) estimates of capital or start-up costs and costs of operation, maintenance, and purchase of services to provide information.

Summary of the total time to prepare, file, and record a SAR: FinCEN PRA burden and cost estimate

Endnotes

[1] Section 358 of the USA PATRIOT Act added language expanding the scope of the BSA to intelligence or counter-intelligence activities to protect against international terrorism.

[2] Treasury Order 180-01 (re-affirmed January 14, 2020).

[3] FinCEN’s System of Records Notice for the BSA Reports System was most recently published at 79 FR 20969 (April 14, 2014).

[4] Public Law 104-13, 44 U.S.C. 3506(c)(2)(A).

[5] The SAR regulatory reporting requirements are currently covered under the following OMB control numbers: 1506-0001 (31 CFR 1020.320 – Reports by banks of suspicious transactions); 1506-0006 (31 CFR 1021.320 – Reports by casinos of suspicious transactions); 1506-0015 (31 CFR 1022.320 – Reports by money services businesses of suspicious transactions); 1506-0019 (31 CFR 1023.320 – Reports by brokers or dealers in securities of suspicious transactions, 31 CFR 1024.320 – Reports by mutual funds of suspicious transactions, and 31 CFR 1026.320 – Reports by futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities of suspicious transactions); 1506-0029 (31 CFR 1025.320 – Reports by insurance companies of suspicious transactions); and 1506-0061 (31 CFR 1029.320 – Reports by loan or finance companies of suspicious transactions). The PRA does not apply to reports by one government entity to another government entity. For that reason, there is no OMB control number associated with 31 CFR 1030.320 – Reports of suspicious transactions by housing government sponsored enterprises. OMB control number 1506-0065 applies to FinCEN Report 111 – SAR.

[6] One hour of burden is estimated under each of the following OMB control numbers: 1506-0001, 1506- 0006, 1506-0015, 1506-0019, 1506-0029, and 1506-0061.

[7] See Table 1 below for a breakdown of the types of financial institutions that filed SARs in 2019. Note that all banks, casinos and card clubs, money services businesses, brokers or dealers in securities, mutual funds, providers of covered insurance products, futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities, loan or finance companies, and housing government sponsored enterprises are required to comply with the SAR regulatory requirements; however, not all financial institutions identify suspicious activity that would warrant a SAR filing. See 31 CFR 1020.320 (banks), 31 CFR 1021.320 (casinos and card clubs), 31 CFR 1022.320 (money services businesses), 31 CFR 1023.320 (brokers or dealers in securities), 31 CFR 1024.320 (mutual funds), 31 CFR 1025.320 (insurance companies), 31 CFR 1026.320 (futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities), 31 CFR 1029.320 (loan or finance companies), and 31 CFR 1030.320 (housing government sponsored enterprises).

[8] Despite the expanded scope, FinCEN has not presented in this notice an estimate of the entire burden that is associated with SAR filings because, as described further in Part 2, FinCEN lacks the granular data to estimate the costs of certain steps in that process.

[9] Numbers are based on actual 2019 filings as reported to the BSA E-Filing System, as of 12/31/2019. Assumptions and estimates are also based on actual 2019 SAR filings.

[10] An original (or initial) report is the first SAR filed on suspicious activity no later than 30 days after the date of initial detection by the filer. (See e.g., 31 CFR 1020.320(a)(3)). A continuing SAR must be filed on suspicious activity that continues after an initial SAR is filed. Continuing reports must be filed on successive 90-day review periods until the suspicious activity ceases, but may be filed more frequently if circumstances warrant. For more information on continuing reports, see page 142 of the FinCEN Suspicious Activity Report (FinCEN SAR) Electronic Filing Requirements – XML Schema 2.0. https://bsaefiling.fincen.treas.gov/docs/XMLUserGuide_FinCENSAR.pdf

[11] In Table 1, the category “Securities/Futures” includes brokers or dealers in securities, mutual funds, futures commission merchants, and introducing brokers in commodities. The category “Undetermined” includes filers with missing, incomplete, or contradictory information about the type of financial institution to which they belong.

[12] In batch filing, a filer submits a single electronic file containing several reports. In discrete filing, the filer fills in an electronic report individually, using a data entry screen that FinCEN provides. While exceptions apply, batch filing is generally used by large-volume filers that have automated the filing process, while discrete filing is generally employed by filers that submit fewer reports per year and rely more on manual data entry methods.

[13] The category “Other” in Table 2 includes securities and futures, housing government sponsored enterprises, providers of covered insurance products, and filers for which the type of financial institution was still being determined at the moment of publication of this notice, as defined above. We adopt the same criteria for the rest of the tables contained in the notice, such as in Tables 4A, 4B, and 5 below.

[14] The percentage of filers contained in each tranche, and the percentage of reports submitted by those filers, are contained in the fields “pct_filers” and “pct_forms”, respectively. The cumulative percentage of filers contained in all tranches up to and including the current one, and the cumulative percentage of reports submitted by such filers, are shown in the fields “cumm_pct_filers” and “cumm_pct_forms”, respectively.

[15] FinCEN Report 111 – SAR contains checkboxes that allow filers to identify a variety of suspicious activities, such as structuring, terrorist financing, fraud, money laundering, and a cyber-event. FinCEN Report 111 – SAR has 18 categories of suspicious activities.

[16] Some filers attach a supplemental file to the report that in general contains a list of individual transactions that raised the alert about a potential suspicious transaction. The length of the narrative is sometimes impacted by whether the filer submits an attachment to the report listing these transactions, or uses the narrative section of the report to include such a list.

[17] The number of suspicious activities identified in each report represents the number of check boxes selected by the filer.

[18] By “in general,” FinCEN is speaking without regard to outliers (e.g., reports exhibiting features that are uncommonly higher or lower than those of the population at large), or that apply to a very narrow type of filer or type of transaction. By “on average,” FinCEN means the mean of the distribution of each subset of the population (although FinCEN uses median labor cost data to calculate weighted hourly worker compensation allocated to each PRA burden hour in Table 6 below).

[19] FinCEN acknowledges that the description of the SAR production process in this notice seems to imply that the process is always linear, with each stage following the previous one. While this situation may reflect a large proportion of the cases reviewed and SARs filed, certain situations will require the filer to return to an earlier stage (such as requiring additional information from the case managers, or drafting several versions of a narrative). The breakdown of the SAR production process in a discrete number of linear stages is intended as a conceptual framework to guide FinCEN’s estimates of the different levels of PRA burden. Such framework does not involve or imply any modification to, or new interpretation of the actual rule text of BSA regulations. The details provided in each stage of the framework serve only as a list of the features FinCEN did or did not consider when estimating the PRA burden of such stage. While FinCEN believes the tasks described in the framework represent the work generally required to produce a SAR, there is no obligation for a financial institution to adopt either formally or informally a process such as the one presented by the framework.

[20] FinCEN recognizes that filers may use the monitoring system to comply with additional BSA and non-BSA regulatory requirements, as well as for other business purposes such as protecting against reputational risks of money laundering and fraud against the filer or the filer’s customers.

[21] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics-National, May 2019, available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm . The most recent data from the BLS corresponds to May 2019. For the benefits component of total compensation, see U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employer’s Cost per Employee Compensation as of December 2019, available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecec.nr0.htm . The ratio between benefits and wages for financial activities, credit intermediation and related activities is $15.80 (hourly benefits)/$31.45 (hourly wages) = 0.502. The benefit factor is 1 plus the benefit/wages ratio, or 1.502. Multiplying each hourly wage by the benefit factor produces the fully-loaded hourly wage per position.

[22] ‘Getting to Effectiveness – Report on U.S. Financial Institution Resources Devoted to BSA/AML and Sanctions Compliance’, Bank Policy Institute, October 29, 2018, available at https://bpi.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/BPI-AML-Sanctions-Study-vF.pdf . See pages 5-7.

[23] The average conversion rate represents the percentage of the total number of cases that, after receiving further review and consideration, warranted the filing of a SAR.

[24] Ibid. The BPI Paper identifies several provisos regarding the correlation among the different metrics (such as the number of alerts related to AML issues only, while the number of SARs filed included both fraud and AML-related transactions). FinCEN considers that these qualifications do not affect the rationale of applying the bank conversion rate of cases into SARs to the full filer population.

[25] The number of original SARs submitted in 2019 (2,335,559) divided by the 42% conversion rate.

[26] FinCEN acknowledges that this estimate simplifies the conversion, stipulating that one case will generate or fail to generate one SAR, when in practice several cases may be reported in a single SAR. It is also possible, while not very probable, that a single case may require the filing of more than one simultaneous SAR.

[27] FinCEN’s assumption is that the clerical work involved in the case review stage would include general administrative and coordination responsibilities, such as the maintaining of agendas, documentation of minutes, assembly of files to be presented to the appropriate authority (for example, a filer’s SAR Committee), and the summarization of the reasons not to file.

[28] FinCEN’s estimate of the traditional average burden hours involved in the SAR filing process was 2 hours for SARs filed individually (60 minutes attributed to reporting, and 60 minutes attributed to recordkeeping), and 2.5 hours per SAR for joint filings (90 minutes attributed to reporting, and 60 minutes attributed to recordkeeping). Joint filings are a single SAR filed by two or more separate financial institutions. This type of filing constitutes less than 1% of total filings.

[29] FinCEN obtained the breakdown by applying the percentages of continuing and original SARs by type of financial institution listed in Table 1, to the burden and cost estimates contained in Tables 8A, 8B, 10, and 13 to 20. Financial institutions the type of which is “undetermined” are included in the “Other nondepository” category in Tables 23 and 24.

[30] See 12 CFR 208.62, 211.5(k), 211.24(f), and 225.4(f) (Federal Reserve Board); 12 CFR 353.3 (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation); 12 CFR 748.1(c) (National Credit Union Administration); 12 CFR 21.11 and 12 CFR 163.180 (Office of the Comptroller of Currency); and 31 CFR Chapter X (FinCEN).