The AML Act of 2020 doesn’t directly change the voluntary information sharing provisions set out in section 314(b) of the USA PATRIOT Act or 31 CFR section 1010.540, but there are provisions in the AML Act that could be used to actively encourage more financial institutions to share information.

On December 10, 2020, FinCEN Director Ken Blanco delivered prepared remarks at the American Bankers Association/American Bar Association Financial Crimes Compliance Conference. Blanco ABA Remarks 12-10-20. Director Blanco’s remarks were wide-ranging, from COVID-19 frauds to cybercrime to business e-mail compromises. He opened his remarks, though, with a lengthy discussion of the private sector voluntary information sharing program under section 314(b) of the USA PATRIOT Act. At a very high level, section 314(b) allows two or more financial institutions and any association of financial institutions, on a voluntary basis and after giving notice to FinCEN of their participation in the 314(b) program, to share information with one another regarding individuals, entities, organizations, and countries suspected of possible terrorist or money laundering activities for the purposes of identifying and reporting activities that may involve terrorist acts or money laundering activities. Since the passage of the Patriot Act in October 2001, and the publication of the final rules for information sharing in September 2002 (those rules are now at 31 CFR 1010.540), there have been a number of guidance documents, fact sheets, and administrative rulings that have sought to clarify some of the aspects of 314(b), such as the form of an association, whether 314(b) provides a safe harbor for sharing information related to fraud or other underlying criminal activities, and what type of customer information can be shared.

Director Blanco’s prepared remarks coincided with the release of a revised FinCEN 314(b) Fact Sheet (Director Blanco called it “important guidance that FinCEN is issuing today which represents much needed clarity regarding how financial institutions may fully utilize FinCEN’s 314(b) information sharing program.”). That guidance, the 314(b) Fact Sheet rescinded three 314(b)-related documents: June 16, 2009 guidance (FIN-2009-G002), a July 25, 2012 administrative ruling, and a November 2016 314(b) Fact Sheet.

(Note: the Fact Sheet is “guidance” and not a regulation or rule, so it does not have the force and effect of law or regulation, and does not bind FinCEN nor any of the Federal functional regulators.)

The main themes of this new 314(b) Fact Sheet are as follows:

- Financial institutions may share under Section 314(b) information relating to activities that they suspect may involve possible terrorist financing or money laundering. This includes, but is not limited to, information about activities they suspect involve the proceeds of a specified unlawful activity (SUA). Importantly, our guidance clarifies that:

-

- Financial institutions do not need to have specific information that these activities directly relate to proceeds of an SUA, or to have identified specific proceeds of an SUA being laundered.

- Financial institutions do not need to have made a conclusive determination that the activity is suspicious.

- Financial institutions may share information about activities as described, even if such activities do not constitute a “transaction.” This includes, for example, an attempted transaction, or an attempt to induce others to engage in a transaction. This clarification is significant and addresses some uncertainty with sharing incidents involving possible fraud, cybercrime, and other predicate offenses when financial institutions suspect those offenses may involve terrorist acts or money laundering activities.

- In addition, the guidance notes that there is no limitation under Section 314(b) on the sharing of personally identifiable information, or the type or medium of information that can be shared (to include sharing information verbally).

- An entity that is not itself a financial institution may form and operate an association of financial institutions whose members can use 314(b). Notably, this includes compliance service providers; and

- An unincorporated association of financial institutions, governed by a contract between its financial institutions’ members, may engage in information sharing under Section 314(b).

Director Blanco also stated that “information sharing among financial institutions through 314(b) is critical to identifying, reporting, and preventing crime and bad acts. It is an important part of how we protect our national security. It can also help financial institutions enhance compliance with their AML/CFT requirements.”

How widely used is the 314(b) voluntary information sharing regime? And how critical is it in identifying, reporting, and preventing crime and bad acts?

The data suggests that 314(b) is not widely used and may not be as critical to identifying and reporting crime and bad acts. That data is from two main reports: (i) an April 2020 FinCEN 314(b) Infographic that provides information on financial institutions participating in the 314(b) program, the number of SAR narratives referencing 314(b), and the number of financial institutions filing SARs referencing 314(b); and (ii) a May 26, 2020 FinCEN notice regarding the costs and burden of filing SARs, described in detail in my June 2, 2020 article, Costs & Burdens of Filing SARs.

Very Few Financial Institutions Participate in the Voluntary 314(b) Information Sharing Program

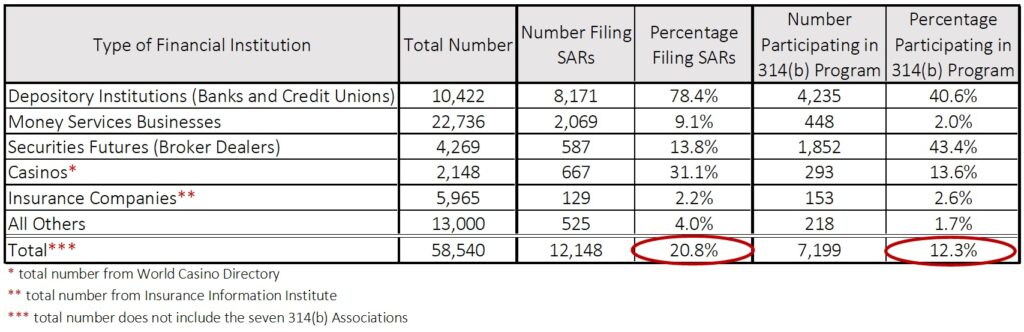

The April 2020 Infographic provides that over 7,000 financial institutions (actually, 7,199) are participating in the 314(b) program. But what the Infographic doesn’t show is the percentage of financial institutions that are participating. For that comparison, we can turn to the Costs & Burdens article, which gives us two figures for each of the eleven types of financial institutions that have mandatory SAR filing requirements. The first is the total number of each category of institution (if known), the second is the number of each category that filed SARs in 2019.

Looking first at the participation in the SAR filing, FinCEN reported in its May 26, 2020 Notice that 12,148 financial institutions filed SARs in 2019. Using either FinCEN data (from other publications) or various industry sources, there are approximately 58,540 financial institutions in the eleven categories of financial institutions that have BSA program and mandatory SAR filing requirements. As can be seen here, overall about 21% of the regulated financial institutions are filing SARs, ranging from 2% of insurance companies to 78% of banks and credit unions.

The FinCEN Infographic shows that 7,199 financial institutions are participating in the voluntary 314(b) information sharing program. The chart shows that is an overall participation rate of 12.3%, or one of every eight regulated financial institutions is participating, ranging from about 2% for MSBs to over 40% for bank and credit unions and broker dealers.

Why is the 314(b) participation rate so low?

There are a number of reasons. First, the vast majority of financial institutions in the United States are very small, have few customers, and file very few SARs. Their resources are already stretched thin complying with the mandatory requirements of a BSA/AML program: risk assessments, establishing and documenting policies and procedures, keeping the required records, monitoring for unusual activity and investigating and reporting suspicious activity, managing audits and exams, etc. So participation in – and spending resources on – a purely voluntary program such as 314(b) is often not commercially and practically feasible. Also, many smaller institutions complain that most 314(b) requests they send to larger institutions are ignored. And the Federal functional regulators have been reluctant to criticize a financial institution for not participating in a voluntary program but can criticize a participating institution for any failures in doing so. As a result, many institutions simply decide to save themselves from regulatory issues by not participating in an otherwise valuable program. Finally, the process of sending and receiving information is manual and inefficient and as a result can impact your SAR filing obligations: Bank A may request certain information from Bank B in order to gain information needed to complete a SAR. Bank A must complete its review of whether activity is suspicious or not within a reasonable period of time, then, once a determination is made that the activity is in fact suspicious, it has 30 days to file a SAR. Often, Bank B doesn’t respond in a timely manner, and Bank A spends valuable investigative time trying to cajole Bank B to respond. This back-and-forth, often to no avail, creates a level of complexity that not many financial institutions want to deal with. So they don’t participate in the 314(b) program at all. In fact, the April 2020 Infographic refers to situations where the SAR filer sent a 314(b) request: “The SAR filer sent a 314(b) request to another financial institution in support of an investigation into suspicious activity. Either the information received was used to further its investigation, ultimately contributing to the filing of the SAR, or the receiving financial institution was unresponsive and the sending financial institution filed a SAR based on their own assessment of the activity.”

(Note: Verafin has an automated 314(b) program that automates the communications and facilitates cross-institutional collaboration on cases. See https://verafin.com/product/314b-information-sharing/)

The Number of SARs Referencing 314(b) is Increasing, But the Percentage of Total SARs Remains Very Low

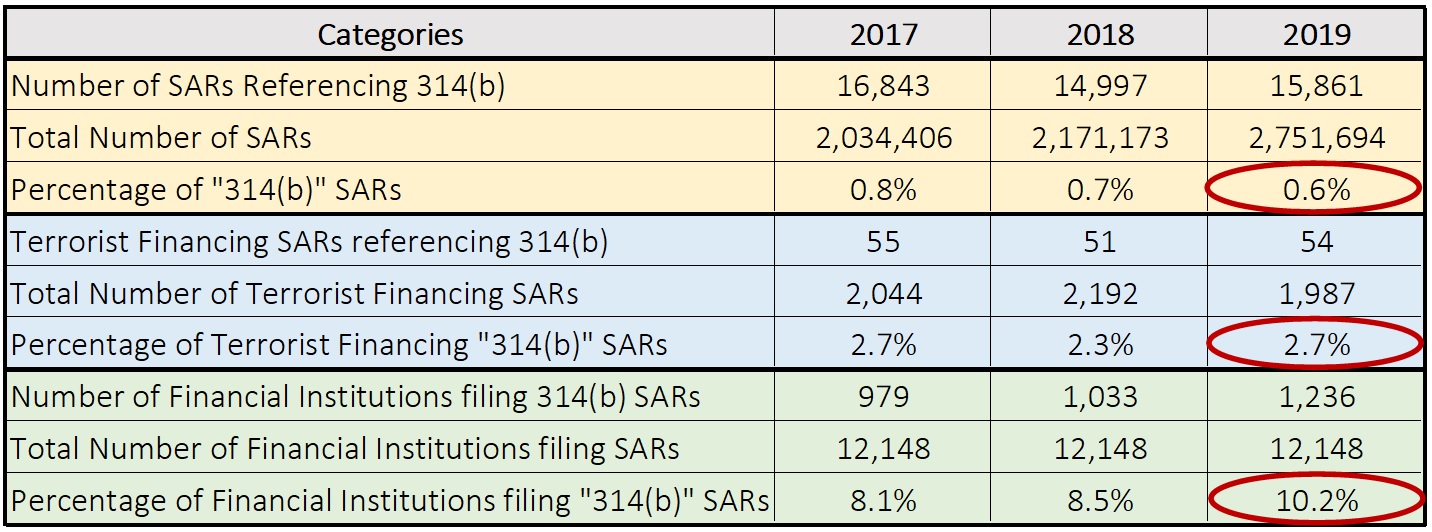

The April 2020 Infographic included some data on the number of SARs that reference 314(b) in the narrative for 2017, 2018, and 2019. That is the top row (in yellow) on the chart below. The Infographic also included some data on the number of financial institutions that filed SARs referencing 314(b) in the narrative: that is the first row in the green section of the chart below.

I have added the other data. The total number of SARs filed in those three years is taken from the FinCEN SAR Stats site: FinCEN SAR Stats. As can be seen from the yellow section of the chart, less than 1 percent of SARs reference 314(b). Arguably, many institutions are utilizing 314(b) but may not refer to it in the SAR narrative. Even if that was the case, and twice as many investigations that led to SARs utilized 314(b), that would still mean that less than 2 percent of all SARs came from investigations involving information shared between financial institutions.

The Infographic also mentioned that “the number of SARs indicating terrorist financing and referencing 314(b) has remained consistent during this three-year period.” So I included FinCEN SAR Stats and we can see, from the blue section of the chart, that about 2.7 percent of all SARs indicating terrorist financing also indicated that the institution utilized the voluntary 314(b) information sharing.

Finally, the Infographic provided that “the number of financial institutions filing SARs referencing 314(b) in the narrative has steadily increased during the past three years, with an increase of 19.7% in 2019”, and it included a chart showing the number of institutions (the top row in the green section). I used the May 26, 2020 FinCEN notice that had 12,148 institutions filing SARs in 2019, then assumed that the number was the same in 2017 and 2018. Even ignoring those two years, the 2019 numbers show that about 10 percent of financial institutions that did file a SAR in 2019, filed a SAR that referenced 314(b).

Encouraging Information Sharing – the AML Act of 2020 is a Good Start

If enacted into law, the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA2020), Division F of the National Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2021, will usher in the biggest changes to the American – and by extension, global – AML/CFT regime since the Patriot Act of 2001. And although information sharing is a feature of the AML Act, section 314(b) is not directly impacted.

Section 6002 of the AML Act describes the six purposes of the Act. The first is “to improve coordination and information sharing among the agencies tasked with administering anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism requirements, the agencies that examine financial institutions for compliance with those requirements, Federal law enforcement agencies, national security agencies, the intelligence community, and financial institutions”.

Section 6101 of the AML Act greatly expands the “purpose” section (section 5311) of the BSA from a single purpose – requiring records and reports where they have a high degree of usefulness to government authorities – to five purposes, including to “establish appropriate frameworks for information sharing among financial institutions, their agents and service providers, their regulatory authorities, associations of financial institutions, the Department of the Treasury, and law enforcement authorities to identify, stop, and apprehend money launderers and those who finance terrorists”.

And section 6214 encourages information sharing and Public-Private Partnerships, and requires the Secretary to convene a supervisory team of agencies, private sector experts, etc., to examine strategies to increase such cooperation.

Reforming the Voluntary 314(b) Private Sector Information Sharing Program

This supervisory team will likely come up with many strategies to increase information sharing. I would start with what may be a bold idea: make 314(b) information sharing mandatory for the largest banks operating in the United States. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) has identified the 2020 list of thirty global systemically important banks (G-SIBs): 314(b) could be amended to make participation mandatory for the G-SIBs and to call for a study of the effective of the mandatory use after two years, and 31 CFR 1010.540 could be revised to require those G-SIBs to demonstrate active participation, both sending requests to other G-SIBs and responding to requests from other G-SIBs. Since the G-SIBs account for most SARs filed (a list of the G-SIBs is available at https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P111120.pdf and it includes JPMorgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Toronto Dominion, among others), this approach could result in greater participation and use by the voluntary users.

Although the Exam Manual provides that “section 314(b) encourages financial institutions and associations of financial institutions located in the United States to share information …” (page 95), section 314(b) does not, in fact, provide that: there is nothing in the section that provides encouragement. And the Exam Manual’s exam procedures for 314(b) do not encourage participation. I would revise 31 CFR 1010.540 and the BSA/AML Exam Manual to actively encourage 314(b) information sharing.

A Better Approach – Combining Sections 314(a) and 314(b) for a True Public-Private Partnership to Fight Financial Crime

In an article posted February 16, 2019 I discussed how a 314(b) association of financial institutions can work directly with law enforcement through the 314(a) public to private sector sharing provisions. Richards on Public-Private Sector Sharing. That article provided, in part:

In Congressional testimony earlier this year, a witness testified that “of the roughly one million SARs filed annually by depository institutions (banks and credit unions), approximately half are filed by only four banks.” What if FinCEN and these four largest financial institutions worked together to share information? And what if they did that with tools already in the anti-money laundering (AML) toolbox?

Here’s how. Remember the language we emphasized above in Section 314(b)? Financial institutions and any association of financial institutions? An “association” can be a tremendously powerful tool when coupled with Section 314(a). Richards describes a scenario where these largest FIs get together to form an information sharing association under 314(b), which not only allows them to share certain information but provides legal protections when doing so, and then the association can work proactively with FinCEN and law enforcement to receive and send names of known targets under 314(a).

“I see this as the wave of the future,” Richards explained. “Otherwise, each individual FI is limited in what it can see and more importantly, what it can understand.” More importantly, he said, it allows FinCEN and FIs to take existing tools and use them “in a more efficient way to solve big problems like human trafficking, contraband smuggling, the opioid crisis, the fentanyl crisis, and other societal problems.”

“Information sharing associations shouldn’t be limited to the biggest FIs, although Greg Baer’s testimony about the largest four FIs, out of about 12,000 in the US, filing 60% of SARs illustrates how powerful such an association could be,” Richards noted. “This association approach, even with smaller institutions, allows law enforcement to target the worst offenders and allow those FIs to better identify those targets and share information between themselves and with the government. “I think it is really positive,” he added, “but it will only work if the regulatory agencies are fully on board and encourage FIs to participate. If there is no regulatory upside for financial institutions, even the best-intentioned of them will think twice before participating in what is otherwise the right thing to do for our communities and country.”

The financial crimes software company Verafin is the technology behind a formal 314(b) association, The Consortium LLC, made up of the five largest US banks and the US branches of two of the largest UK banks (see notices published in the Federal Register on August 9, 2018 for Standard Chartered (83 FR 39440) and on October 5, 2018 for HSBC (83 FR 50371) “to engage de novo through a newly formed entity, The Consortium, LLC, in data processing activities”. Through a formal process pursuant to and in compliance with 314(a), The Consortium members receive the names of entities that a federal law enforcement agency has identified as being engaged in, or is reasonably suspected based on credible evidence of engaging in, terrorist activity or money laundering.

The multiplier effect of a 314(b) association of institutions working together is quite remarkable. To illustrate, assume the FBI submitted 10 names of known targets to FinCEN, which then forwarded those names to each of the seven Consortium member institutions. Those seven then each review their records to determine whether they maintain or have maintained accounts for, or have engaged in transactions with, any of those 10 entities. Those accounts may have related parties, and the transactions will have sending or receiving parties. And each member may have filed SARs on some or all of the entities. Assume that each member identifies an additional 5 “suspects”.

The results – now 10 targets and 35 new suspects – are then shared between the members of The Consortium (again, as a 314(b) association of financial institutions) and, using the Verafin technology, the members can then conduct a joint investigation. This joint investigation may reveal another 15 suspects. The Consortium shares these 60 names with the FBI and FinCEN, which may have identified 10 of the suspects but not linked them to the original case, or may not have known about the other 40 “new” suspects.

The ultimate output is individual SARs filed by the individual member institutions (a joint SAR or joint SARs remain legally impractical) supported by a joint intelligence memo for law enforcement.

Conclusion

One of the main purposes of the AML Act of 2020 is to improve coordination and information sharing among and between the public sector and private sector. In order to do that, the voluntary sharing of information between financial institutions – created by section 314(b) of the USA PATRIOT Act and administered by regulations set out in 31 CFR section 1010.540 – should become mandatory for the largest financial institutions (the thirty global systemically important banks, or G-SIBs) and should be actively encouraged by FinCEN and the Federal functional regulators. And associations of financial institutions, like The Consortium, LLC, should also be encouraged to be formed and work with the public sector to share information and perform cross-institutional, collaborative investigations and reports.