FinCEN has issued an updated advisory on Business Email Compromise (BEC) fraud schemes: FinCEN 2019 BEC Advisory . At the same time it issued a Financial Trend Analysis that provides some details on what FinCEN is seeing from the Suspicious Activity Reports on BEC schemes: BEC Trends

FIN-2019-A005 Updated Advisory on Email Compromise Fraud Schemes Targeting Vulnerable Business Processes (July 16, 2019)

This 2019 Advisory is 12 pages long, and supersedes the 2016 advisory: FinCEN 2016 BEC Advisory. Highlights of the 2019 Advisory can be summarized as follows:

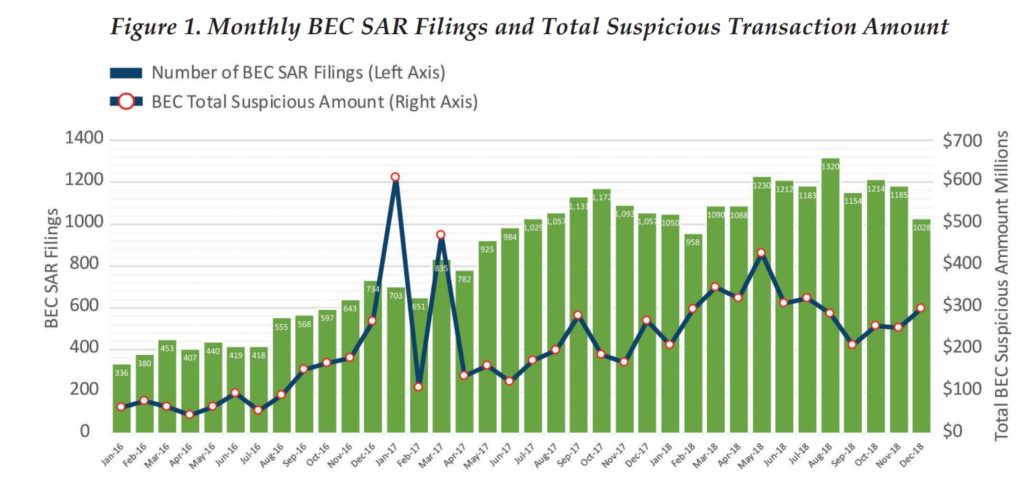

Instances of BEC reported to FinCEN have climbed from averaging just under 500 reports per month (averaging $110 million monthly in total attempted BEC thefts) in 2016 to over 1,100 monthly reports (averaging over $300 million monthly in total attempted BEC thefts) in 2018. Since November 2016, financial institutions reported over 6,000 instances and over $2.6 billion in attempted and successful transactions affiliated with suspected money laundering activity through BEC schemes.

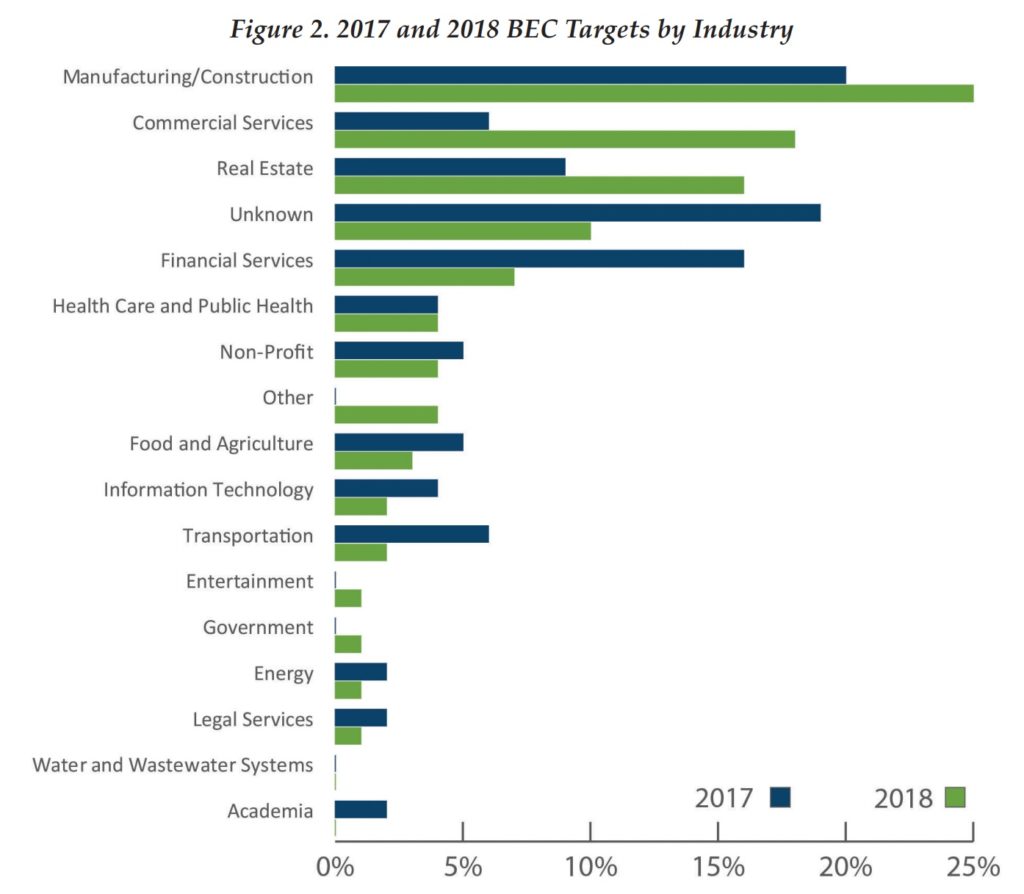

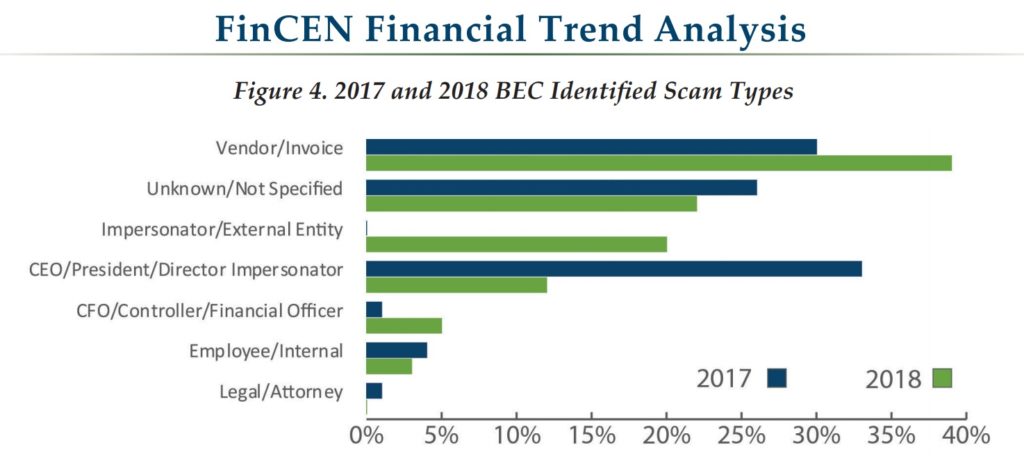

Three observed trends since the 2016 Advisory. First, a concentration of targeting of particular sectors: manufacturing and construction (25% of reported BEC cases), commercial services (18%), and real estate (16%). Second, the majority of BEC incidents (reported in the Trends Analysis at 73%) affecting U.S. financial institutions and their customers are increasingly involving initial domestic funds transfers, rather than international, likely taking advantage of money mule networks across the United States to move stolen funds. Third, the two most common impersonations – CEO and vendor – are trending in different directions: CEO impersonations are trending down (from 33% of reported incidents in 2017 to 12% in 2018), and vendor impersonations are trending up (from 30% of incidents in 2017 to 39% in 2018, becoming the most common BEC method). FinCEN also noted that the average transaction amount for BECs impersonating a vendor or client invoice was $125,439, compared with $50,373 for impersonating a CEO.

A BEC scheme’s probability of success and the potential payout from fraudulent payment instructions often depends on (1) the criminal’s knowledge of their victim’s normal business processes by leveraging publicly available information about the victim organization’s vendors, contracts, and business processes, and (2) weaknesses in the victim’s authorization and authentication protocols.

In this 2019 Advisory, FinCEN broadens its definitions of email compromise fraud activities to clarify that such fraud targets a variety of types of entities and may be used to misdirect any kind of payment (not just wire transfers) or transmittal of other things of value. While many email compromise fraud scheme payments are carried out via wire transfers (as originally stated in the 2016 BEC Advisory), FinCEN has observed BEC schemes fraudulently inducing funds or value transfers through convertible virtual currency payments, ACH transfers, and purchases of gift cards.

The 2019 Advisory also expands the types of victims beyond commercial businesses. FinCEN analysis has indicated criminal groups use a variety of techniques to conduct BEC fraud against individuals, particularly and increasingly those with high net worth, and entities that routinely use email to make or arrange payments between partners, customers, or suppliers. Targets of these schemes fall outside of the definition of traditional business customers, such as government entities and non-profit organizations or even the financial institutions themselves.

Footnote 7 provides that “The definitions of email compromise fraud, BEC, and EAC supersede the definitions in the 2016 BEC Advisory.” Those definitions are (and the red font indicates changes from 2016):

Email Compromise Fraud: Schemes in which 1) criminals compromise[1] the email accounts of victims to send fraudulent payment instructions to financial institutions or other business associates in order to misappropriate funds or value; or in which 2) criminals compromise the email accounts of victims to effect fraudulent transmission of data that can be used to conduct financial fraud. The main types of email compromise, the definitions of which have been modified to reflect the expansion of victims being targeted, include:

Business Email Compromise (BEC): Targets accounts of financial institutions or customers of financial institutions that are operational entities, including commercial, non-profit, nongovernmental, or government entities.

Email Account Compromise (EAC): Targets personal email accounts belonging to an individual.

BEC Fraud against Governments – BEC frauds have targeted accounts used for pension funds, payroll accounts, and contracted services. Schemes against government victims are consistent with other common typologies in BEC fraud. BEC schemes targeting government entities also often include vendor impersonation.

BEC Fraud against Educational Institutions – In 2016, financial institutions reported to FinCEN over 160 incidents of BEC targeting educational institutions where criminals attempted to steal over $50 million. The education sector has the largest concentration of high-value BEC attempts in financial sector reporting, even though only approximately 2% of BEC incidents affected educational institutions in 2017. Schemes against educational institutions frequently involve vendor impersonation. Attackers use authentic-looking payment requests to direct funds to domestic bank accounts they control. Large-scale construction and renovation projects have repeatedly been targets of high-dollar thefts.

BEC Fraud against Financial Institutions – In some cases, BEC actors directly target the financial institutions themselves. This scheme typically involves spoofing bank domains and sending what appear to be credible messages to imitate official communications between bank employees, such as sending emails that appear to be from a financial institution’s SWIFT (wire operations) department with payment instructions and SWIFT reference numbers in the email text to enhance its apparent legitimacy to the victim.

Information Sharing – The 2019 Advisory encourages financial institutions to use 314(b) to share information. FinCEN points out that many beneficiaries of BEC schemes play roles in larger networks of criminal activity and laundering of funds from illicit activity (“FinCEN encourages financial institutions to share valuable information about BEC beneficiaries and perpetrators, for purposes of identifying and, where appropriate, reporting activities that they suspect may involve possible terrorist activity or money laundering.”).

The 2019 Advisory includes a section on information for US financial institutions (which supersedes the 2016 advisory):

Risk Management Considerations – In determining the inherent risk of BEC, financial institutions should consider the level of information available publicly about key financial counterparties and processes, including information on public websites or on the darknet (e.g., email account login credentials that have been compromised and posted for sale). Financial institutions need to also consider its procedures and processes relating to how it (1) authenticates participants in communications,( 2) authorizes transactions, and (3) communicates information and changes about transactions. A multi-faceted transaction verification process, as well as training and awareness-building to identify and avoid spear phishing schemes, are critical.

Response and Recovery of Funds – To request immediate assistance in recovering BEC-stolen funds, financial institutions should file a complaint with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), contact their local FBI field office, or contact the nearest USSS field office. These agencies are part of FinCEN’s Rapid Response Program (RRP). Financial institutions should also use the 314(b) information sharing process to request assistance from other financial institutions involved in (victims of or unwitting participants in) the scheme.

Suspicious Activity Reporting – Financial institutions should provide all pertinent available information on the event and associated suspicious activity, including cyber-related information, in the SAR form and narrative. Specifically, the following information is highly valuable to law enforcement and FinCEN in investigating BEC/EAC fraud:

Transaction details:

1) Dates and amounts of suspicious transactions;

2) Sender’s identifying information, account number, and financial institution;

3) Beneficiary’s identifying information, account number, and financial institution; and

4) Correspondent and intermediary financial institutions’ information, if applicable.

Scheme details:

1) Relevant email addresses and associated Internet Protocol (IP) addresses with their respective timestamps;

2) Description and timing of suspicious email communications and any involved compromised or impersonated parties; and

3) Description of related cyber-events and use (or compromise) of particular technology in the conduct of the fraud. For example, financial institutions should consider including any of the following information or evidence related to the email compromise fraud:

- a) Email auto-forwarding

- b) Inbox sweep rules or sorting rules set up in victim email accounts

- c) A malware attack, and

- d) The authentication protocol that was compromised (i.e., single-factor or multi-factor, one-step or multi-step, etc.)

[1] Criminals engaged in email compromise fraud may directly compromise email accounts through unauthorized electronic intrusions in order to leverage the compromised account for sending messages, or they may instead impersonate an email account through spoofing the email address or using an email account closely resembling a known counterparty or customer’s email address (i.e., that is slightly altered by adding, changing, or deleting one or more characters).