The Senate Banking Committee’s top Republican (Senator Crapo from Idaho) and top Democrat (Senator Brown from Ohio) have joined forces to draft the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act. It takes some of what the House passed in HR2513, the Corporate Transparency Act, and replicates most of what the Senate has been horse-trading on with the ILLICIT CASH Act (S2563), and adds a few other provisions: 214 pages of provisions.

The Senate Banking Committee’s top Republican (Senator Crapo from Idaho) and top Democrat (Senator Brown from Ohio) have joined forces to draft the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act. It takes some of what the House passed in HR2513, the Corporate Transparency Act, and replicates most of what the Senate has been horse-trading on with the ILLICIT CASH Act (S2563), and adds a few other provisions: 214 pages of provisions.

If enacted, it would be the biggest revision to the U.S. AML/CFT regime since the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001. The main legislation for the AML/CFT regime is found in Title 31 of the US Code. 31 USC 5311 (the purpose of the BSA) and 5318 (the program and reporting requirements) will materially change, four new sections (5333-5336) will be added, two new BSAAG subcommittees will be created, and of course a FinCEN database of beneficial ownership information will be created to house some legal entity beneficial ownership information (more on that in another article).

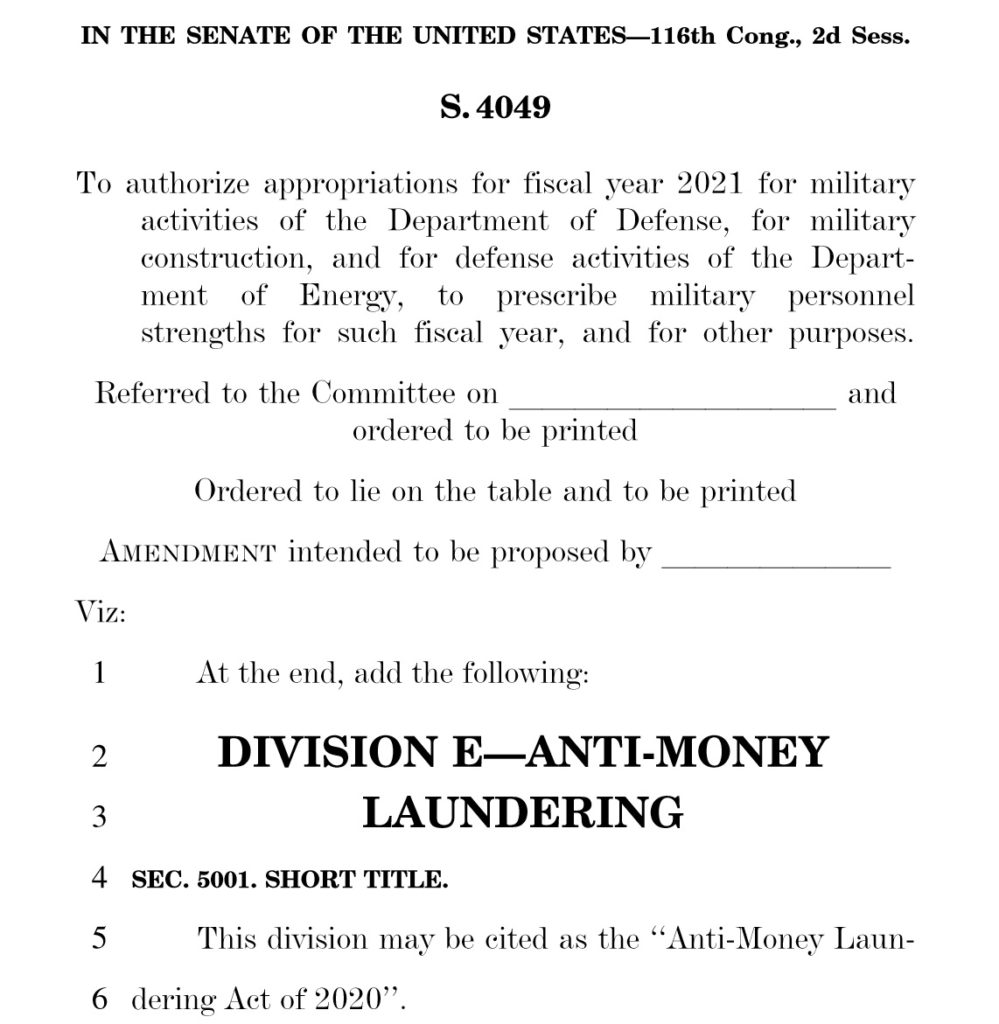

Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020

The proposed AML Act of 2020 would be tacked on to the back end – Division E – of the 2021 Defense Appropriations bill. So the titles for the Act begin at title 51 – actually the Roman numeral LI. There are five titles:

- Title LI – Strengthening Treasury Financial Intelligence, Anti-Money Laundering [AML], and Countering the Financing of Terrorism [CFT] Programs

- Title LII – Modernizing the AML and CFT Systems

- Title LIII – Improving AML and CFT Communication, Oversight, and Processes

- Title LIV – Establishing Beneficial Ownership Reporting Requirements

- Title LV – Miscellaneous

Section 5201 – Annual Reporting Requirements

This article focuses solely on section 5201 of Title LII. Why? It includes my long-sought-after SAR feedback from law enforcement, while at the same time resurrects the long-forgotten section 314(d) of the USA PATRIOT Act.

In a nutshell, section 5201 is a “pay to play” requirement imposed on law enforcement and the intelligence community. At requires the Attorney General, on behalf of federal and state prosecutors and law enforcement agencies, to deliver an annual report and, once every five years a broader long-term trending report, to the Secretary of the Treasury, setting out statistics, metrics, and other information on the use of BSA reports. The annual report must include:

- The frequency with which the BSA reports contains actionable information that leads to, among other things, actions by law enforcement agencies such as grand jury subpoenas, and actions by intelligence, national security, and homeland security agencies;

- Calculations on the time between the BSA reporting and the use of the data by law enforcement or intelligence agencies;

- An analysis of the transactions associations with the BSA reports, including whether the accounts were held by legal entities or persons, and any trends or patterns in cross-border activity;

- The number of legal entities and persons identified by the BSA reports;

- The extent to which arrests, indictments, convictions, etc., were related to the reports; and

- Data on state and federal investigations that resulted from the reports.

The five-year report would focus on longer-term trends, patterns and threats: retrospective trends and emerging patterns and threats.

And what would the Secretary of the Treasury do with these reports? That is covered by subsection (d) of section 5201, which provides that the Secretary shall use these reports

- To help assess the usefulness of BSA reports;

- “to enhance feedback and communications with financial institutions and other entities subject to the requirements under the BSA, including by providing more detail in the reports published and distributed under section 314(d) of the USA PATRIOT Act (31 USC s. 5311 note);

- to assist FinCEN in considering revisions to the reporting requirements promulgated under section 314(d) of the USA PATRIOT Act (31 USC s. 5311 note).

The result? This July 2020 proposed AML legislation would require the public sector consumers of BSA reports to provide feedback to the private sector producers of those reports – essentially a “pay to play” requirement, and that feedback would be through the almost 20-year old provision of the USA PATRIOT Act, section 314(d).

I’ve written about both of these things.

On July 30, 2019 I published an article titled “SAR Feedback? What Ever Happened to Section 314(d)?” See https://regtechconsulting.net/aml-regulations-and-enforcement-actions/sar-feedback-what-ever-happened-to-section-314d/ I wrote:

Wouldn’t it be great if Treasury published a report, perhaps semi-annually, that contained a detailed analysis identifying patterns of suspicious activity and other investigative insights derived from suspicious activity reports (SARs) and investigations conducted by federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies (to the extent appropriate) and distributed that report to financial institutions that filed those SARs?

To get Treasury to do that, though, would probably require Congress to pass a law compelling it to do so.

Hold it. Congress did pass that law. Almost 18 years ago. And, by all accounts, it’s still on the books. What happened to those semi-annual reports? When did they begin? If they began, when did they end?

Section 314(d) – Its Origins

What became 314(d) was introduced in the House version of what became the USA PATRIOT Act. The House version, the Financial Anti-Terrorism Act, was introduced on October 3, 2001. It was marked up by the House Financial Services Committee on October 11. The Senate version, originally titled the Uniting and Strengthening America Act, or USA Act, was introduced on October 4th and had sections 314(a) (public to private sector information sharing), 314(b) (cooperation among financial institutions, or private-to-private sector information sharing), and 314(c) (“rule of construction”). There was no 314(d) in that early version.

On October 17th, HR 3004, the Financial Anti-Terrorism Act, was passed by the House 412-1. Title II was “public-private cooperation”. Section 203 was:

“Reports to the Financial Services Industry on Suspicious Financial Activities – at least once each calendar quarter, the Secretary shall (1) publish a report containing a detailed analysis identifying patterns of suspicious activity and other investigative insights derived from suspicious activity reports and investigations conducted by federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to the extent appropriate; and (2) distribute such report to financial institutions as defined in section 5312 of title 31, US code.”

The Senate and House versions were reconciled, and on October 23rd the House Congressional Record shows a consideration of what was then the USA PATRIOT Act. That version of the bill then included what had been section 203 and was now 314(d). It was the same, except instead of a quarterly report it was a semi-annual report (“at least once each calendar quarter” was changed to “at least semiannually”).

SAR Activity Review – Was That The Answer to 314(d)?

The ABA has written, and at least one former FinCEN employee has stated that the “SAR Activity Review – Trends, Tips, and Issues” was the response to 314(d). The SAR Activity Reviews were excellent resources. They contained sections on SAR statistics, national trends and analysis, law enforcement cases, tips on SAR form preparation and filing, issues and guidance, and an industry forum. The first SAR Activity Review noted that it was published under the auspices of the BSAAG, was to be published semi-annually in October and April, and was “the product of a continuing collaboration among the nation’s financial institutions, federal law enforcement, and regulatory agencies to provide meaningful information about the preparation, use, and utility of SARs.” Although that certainly sounds like it is responsive to section 314(d), there is no reference to 314(d).

And the first SAR Activity Review was published more than a year before 314(d) was passed. Even the first SAR Activity Review published after the enactment of the USA PATRIOT Act and section 314(d) – the 4th issue published on July 31, 2002 – didn’t make any reference to 314(d). Beginning with the 6th issue of the SAR Activity Review, published in October 2003, the authors broke out the statistics from the “Trends, Tips & Issues” document and published a separate, and more detailed, “SAR Activity Review – By The Numbers”. The last SAR Activity Review (the 23rd) and the last “By The Numbers” (the 18th) were published on April 30, 2013. None of those forty-one publications referenced 314(d). After the SAR Activity Reviews stopped, FinCEN continued to publish “SAR Statistics”, and did so three times from June 2014 through March 2017. For the last few years, FinCEN has maintained SAR Stats on its website – https://www.fincen.gov/reports/sar-stats – that is updated on a monthly basis. Those statistics are useful, but cannot be thought of as “containing a detailed analysis identifying patterns of suspicious activity and other investigative insights derived from suspicious activity reports and investigations conducted by federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to the extent appropriate”, quoting the 314(d) language.

Does Anyone Know What Happened to 314(d)?

I don’t have the answer to that question. Perhaps 314(d) is seen as satisfied by the accumulation of advisories, guidance, bulletins, etc., published by FinCEN and other Treasury bureaus and agencies and departments from time to time. Perhaps there is a Treasury Memorandum out there that I’m not aware of that provides a simple explanation. Perhaps not: most BSA/AML experts I speak with are not even aware of 314(d), and if the SAR Activity Review did satisfy the spirit and intent of 314(d), the last one was published more than six years ago. But everyone in the private sector BSA/AML risk management space has been clamoring for more feedback from law enforcement and FinCEN on the effectiveness and usefulness of their SAR filings. Perhaps a renewed (or any) focus on 314(d) is the answer. The revival of 314(d) could give FinCEN the mandate they’ve been looking for to provide more valuable information to the private sector producers of Suspicious Activity Reports. We would all benefit.

Public Sector is Going to Have to Pay in Order to Play With the Private Sector’s BSA Reports

On November 21, 2019 I wrote an article titled “Like Sam Loves Free Fried Chicken, Law Enforcement Loves ‘Free’ Suspicious Activity Reports … But What If Law Enforcement Had to Earn the Right to Use the Private Sector’s ‘Free’ SARs?” See https://regtechconsulting.net/fintech-financial-crimes-and-risk-management/like-sam-loves-free-fried-chicken-law-enforcement-loves-free-suspicious-activity-reports-but-what-if-law-enforcement-had-to-earn-the-right-to-use-the-private-sector/. That article provided:

Eleven year-old Sam Caruana of Buffalo, New York waited outside a Chick-fil-A restaurant in the freezing cold in order to be one of the 100 people given free fried chicken for one year (actually, one chicken sandwich a week for fifty-two weeks). In a video that went viral (Sam Caruana YouTube – Free Chicken), young Sam explained that he simply loved fried chicken, and he’d stand in the cold for free fried chicken.

Just as Sam loves free fried chicken, law enforcement loves free Suspicious Activity Reports, or SARs. In the United States, over 30,000 private sector financial institutions – from banks to credit unions, to money transmitters and check cashers, to casinos and insurance companies, to broker dealers and investment advisers – file more than 2,000,000 SARs every year. And it costs those financial institutions billions of dollars to have the programs, policies, procedures, processes, technology, and people to onboard and risk-rate customers, to monitor for and identify unusual activity, to investigate that unusual activity to determine if it is suspicious, and, if it is, to file a SAR with the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN. From there, hundreds of law enforcement agencies across the country, at every level of government, can access those SARs and use them in their investigations into possible tax, criminal, or other investigations or proceedings. To law enforcement, those SARs are, essentially, free. And like Sam loves free fried chicken, law enforcement loves free SARs. Who wouldn’t?

But should those private sector SARs, that cost billions of dollars to produce, be “free” to public sector law enforcement agencies? Put another way, should the public sector law enforcement agency consumers of SARs need to provide something in return to the private sector producers of SARs?

I say they should. And here’s what I propose: that in return for the privilege of accessing and using private sector SARs, law enforcement shouldn’t have to pay for that privilege with money, but with effort. The public sector consumers of SARs should let the private sector producers know which of those SARs provide tactical or strategic value.

A recent Mid-Size Bank Coalition of America (MBCA) survey found the average MBCA bank had: 9,648,000 transactions/month being monitored, resulting in 3,908 alerts/month (0.04% of transactions alerted), resulting in 348 cases being opened (8.9% of alerts became a case), resulting in 108 SARs being filed (31% of cases or 2.8% of alerts). Note that the survey didn’t ask whether any of those SARs were of interest or useful to law enforcement. Some of the mega banks indicate that law enforcement shows interest in (through requests for supporting documentation or grand jury subpoenas) 6% – 8% of SARs.

I argue that the Alert/SAR and even Case/SAR ratios are all of interest, but tracking to SARs filed is a little bit like a car manufacturer tracking how many cars it builds but not how many cars it sells, or how well those cars perform, how long they last, and how popular they are. And just like the automobile industry measuring how many cars are purchased, the better measure for AML programs is “SARs purchased”, or SARs that provide value to law enforcement.

Also, there is much being written about how machine learning and artificial intelligence will transform anti-money laundering programs. Indeed, ML and AI proponents are convinced – and spend a lot of time trying to convince others – that they will disrupt and revolutionize the current “broken” AML regime. Among other targets within this broken regime is AML alert generation and disposition and reducing the false positive rate. The result, if we believe the ML/AI community, is a massive reduction in the number of AML analysts that are churning through the hundreds and thousands of alerts, looking for the very few that are “true positives” worthy of being labelled “suspicious” and reported to the government. But the fundamental problem that every one of those ML/AI systems has is that they are using the wrong data to train their algorithms and “teach” their machines: they are looking at the SARs that are filed, not the SARs that have tactical or strategic value to law enforcement.

Tactical or Strategic Value Suspicious Activity Reports – TSV SARs

The best measure of an effective and efficient financial crimes program is how well it is providing timely, effective intelligence to law enforcement. And the best measure of that is whether the SARs that are being filed are providing tactical or strategic value to law enforcement. How do you determine whether a SAR provides value to law enforcement? One way would be to ask law enforcement, and hope you get an answer. That could prove to be difficult. Can you somehow measure law enforcement interest in a SAR? Many banks do that by tracking grand jury subpoenas received to prior SAR suspects, law enforcement requests for supporting documentation, and other formal and informal requests for SARs and SAR-related information. As I write above, an Alert-to-SAR rate may not be a good measure of whether an alert is, in fact, “positive”. What may be relevant is an Alert-to-TSV SAR rate.

A TSV SAR is one that has either tactical value – it was used in a particular case – or strategic value – it contributed to understanding a typology or trend. And some SARs can have both tactical and strategic value. That value is determined by law enforcement indicating, within seven years of the filing of the SAR (more on that later), that the SAR provided tactical (it led to or supported a particular case) or strategic (it contributed to or confirmed a typology) value. That law enforcement response or feedback is provided to FinCEN through the same BSA Database interfaces that exist today – obviously, some coding and training will need to be done (for how FinCEN does it, see below). If the filing financial institution does not receive a TSV SAR response or feedback from law enforcement or FinCEN within seven years of filing a SAR, it can conclude that the SAR had no tactical or strategic value to law enforcement or FinCEN, and may factor that into decisions whether to change or maintain the underlying alerting methodology. Over time, the financial institution could eliminate those alerts that were not providing timely, actionable intelligence to law enforcement. And when FinCEN shares that information across the industry, others could also reduce their false positive rates.

FinCEN’s TSV SAR Feedback Loop

FinCEN is working to provide more feedback to the private sector producers of BSA reports. As FinCEN Director Ken Blanco recently stated:[1]

“Earlier this year, FinCEN began the BSA Value Project, a study and analysis of the value of the BSA information we receive. We are working to provide comprehensive and quantitative understanding of the broad value of BSA reporting and other BSA information in order to make it more effective and its collection more efficient. We already know that BSA data plays a critical role in keeping our country strong, our financial system secure, and our families safe from harm — that is clear. But FinCEN is using the BSA Value Project to improve how we communicate the way BSA information is valued and used, and to develop metrics to track and measure the value of its use on an ongoing basis.”

FinCEN receives every SAR. Indeed, FinCEN receives a number of different BSA-related reporting: SARs, CTRs, CMIRs, and Form 8300s. It’s a daunting amount of information. As FinCEN Director Ken Blanco noted in the same speech:

FinCEN’s BSA database includes nearly 300 million records — 55,000 new documents are added each day. The reporting contributes critical information that is routinely analyzed, resulting in the identification of suspected criminal and terrorist activity and the initiation of investigations.

“FinCEN grants more than 12,000 agents, analysts, and investigative personnel from over 350 unique federal, state, and local agencies across the United States with direct access to this critical reporting by financial institutions. There are approximately 30,000 searches of the BSA data taking place each day. Further, there are more than 100 Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) review teams and financial crimes task forces across the country, which bring together prosecutors and investigators from different agencies to review BSA reports. Collectively, these teams reviewed approximately 60% of all SARs filed.

Each day, law enforcement, FinCEN, regulators, and others are querying this data: 7.4 million queries per year on average. Those queries identify an average of 18.2 million filings that are responsive or useful to ongoing investigations, examinations, victim identification, analysis and network development, sanctions development, and U.S. national security activities, among many, many other uses that protect our nation from harm, help deter crime, and save lives.”

This doesn’t tell us how many of those 55,000 daily reports are SARs, but we do know that in 2018 there were 2,171,173 SARs filed, or about 8,700 every (business) day. And it appears that FinCEN knows which law enforcement agencies access which SARs, and when. And we now know that there are “18.2 million filings that are responsive or useful to ongoing investigations, examinations, victim identification, analysis and network development, sanctions development, and U.S. national security activities” every year. But which filings?

The law enforcement agencies know which SARs provide tactical or strategic value, or both. So if law enforcement finds value in a SAR, it should acknowledge that, and provide that information back to FinCEN. FinCEN, in turn, could provide an annual report to every financial institution that filed, say, more than 250 SARs a year (that’s one every business day, and is more than three times the number filed by the average bank or credit union). That report would be a simple relational database indicating which SARs had either or both tactical or strategic value. SAR filers would then be able to use that information to actually train or tune their monitoring and surveillance systems, and even eliminate those alerting systems that weren’t providing any value to law enforcement.

Why give law enforcement seven years to respond? Criminal cases take years to develop. And sometimes a case may not even be opened for years, and a SAR filing may trigger an investigation. And sometimes a case is developed and the law enforcement agency searches the SAR database and finds SARs that were filed five, six, seven or more years earlier. Between record retention rules and practical value, seven years seems reasonable.

Law enforcement agencies have tremendous responsibilities and obligations, and their resources and budgets are stretched to the breaking point. Adding another obligation – to provide feedback to the banks, credit unions, and other private sector institutions that provide them with reports of suspicious activity – may not be feasible. But the upside of that feedback – that law enforcement may get fewer, but better, reports, and the private sector institutions can focus more on human trafficking, human smuggling, and terrorist financing and less on identifying and reporting activity that isn’t of interest to law enforcement – may far exceed the downside.

Free Suspicious Activity Reports are great. But like Sam being prepared to stand in the freezing cold for his fried chicken, perhaps law enforcement is prepared to let us know whether the reports we’re filing have value.

Conclusion

As of this writing – July 3, 2020 – it remains to be seen whether the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 will become law, or what parts of the Act will become law. But section 5201, which requires the public sector consumers of the BSA reports produced by the private sector to provide feedback to the private sector on the usefulness of those reports. This is a critically important, long-awaited development in the US AML/CFT regime.

For more on alert-to-SAR rates, the TSV feedback loop, machine learning and artificial intelligence, see other articles I’ve written:

The TSV SAR Feedback Loop – June 4 2019

AML and Machine Learning – December 14 2018

Rules Based Monitoring – December 20 2018

FinCEN FY2020 Report – June 4 2019

FinCEN BSA Value Project – August 19 2019

BSA Regime – A Classic Fixer-Upper – October 29 2019

[1] November 15, 2019, prepared remarks for the Chainalysis Blockchain Symposium, available at https://www.fincen.gov/news/speeches/prepared-remarks-fincen-director-kenneth-blanco-chainalysis-blockchain-symposium